Crossrail’s Technical Papers Competition

Document

type: Micro-report

Author:

Mike Black BSc(Hons) MSc CSci CGeol FGS, Brigid Leworthy DMS MSc MIET

Publication

Date: 13/03/2018

-

Abstract

On a project the size and complexity of Crossrail there is much interest from professionals from all industries in learning how such a project implements new and innovative processes and different ways of working. To this end it was expected that employees and contractors would be requesting to deliver papers and journal articles on specific topics for wider industry use. To manage and encourage that process Crossrail devised the “Technical Papers Competition”.

This paper outlines how the competition was devised and implemented and what lessons were learned along the way. It has proved to be popular with employees and would be of interest to any large project looking to harness the key learning from the projects they are undertaking.

-

Read the full document

1. Introduction and Context

On a project of the size and complexity of Crossrail there is heightened interest from professionals from all industries. Many of the professional bodies are excited by the possibility of new and innovative processes and different ways of working. There is an appetite for learning and to that end the relevant appropriate professional bodies look to their members to provide some of the insight in order to keep the professions up to date and abreast of any new approaches undertaken. On the Crossrail project this was expected to lead to a large number of requests from employees and contractors to deliver papers and journal articles for wider industry use. In order to manage these requests, and reduce the amount of time and resource needed to vet and approve them, a system needed to be introduced. The company did not wish to dampen enthusiasm and felt that producing technical papers to chart the progress of the project was really worthwhile. A solution was sought and the idea of a “Technical Papers Competition” (TPC) was born. The idea was driven by the Chief Engineer at the time and under his direction the process for the competition was devised and incorporated within the engineering team workload.

2. The Technical Papers Competition Explained

2.1 Basis of the Competition

The technical papers competition sought papers from those working on Crossrail and was based on three key rules:

- The author/s must have worked on the specific project

- The competition paper could not bring the company into disrepute

- The part of the project being discussed had to have been completed so that the outcomes were known

2.2 Structure and Judging of the Competition

Crossrail had set up independent panels to provide an additional objective oversight and advice for the project. Crossrail commissioned the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) to set this up, and participants were independent experts in their fields. There were expert panels for Civils/Finance/Procurement/Architecture. They met monthly, co-ordinated by the head of the engineering expert panel.

This provided the Chief Engineer with a format for dealing with technical papers and the Technical Papers Competition (TPC) was introduced and run by the Chief Engineers Group (CEG). A number of discipline experts from within The Chief Engineer’s Group reviewed and judged the papers, usually on the basis of two reviewers per paper. Two or three members of an independently appointed engineering expert panel then reviewed the shortlist and ratified the decision of the judges once the judging was complete. An overall winner would be selected and the next best two or three papers would be recognised as “Commended” or “Highly Commended”. This remained the process for each year the competitions were held.

So the TPC was run and driven from within the project itself, but an expert external panel was able to be utilised for reviewing the final shortlisted TPC papers submitted. As outlined above, each paper had two judges. The two judges for each paper were the discipline head most appropriate for the topic of the paper, (i.e. Head of Geotechnics for geotechnical papers, Head of MEP for MEP topics etc), and a second head of an unrelated discipline. This meant that both the technical content, and the “readability” of the papers were assessed.

The competition was designed to run annually, giving plenty of notice for the call for papers and adequate time for the authors to submit.

From the outset a very clear structured format was in place. With the process and judging structure in place all that was left to do was develop a clear set of rules and guidelines for the participants to follow. As papers were often then used for presentation/contribution to professional bodies, the guidelines were developed from common paper writing guidelines as required by the professional bodies so that they were prepared in a consistent format. These have remained fairly consistent throughout the lifetime of the competition and a copy of the most recent rules and author guidelines are included as reference documents attached to this paper.

The Institution of Civil Engineers could see the value of these papers which also charted the progress of the project and the issues being dealt with. Crossrail was therefore able to arrange with the ICE for them to publish the papers received each year into one concise volume of highly topical subjects, disseminating the learning from the largest infrastructure project in Europe.

2.3 Timeline of the Competition

The competition takes place each year and approximately follows the timeline shown in Figure 1. The competition is open to anyone who has worked on the project, including employees, contractors, project managers.

The competition does not have a formal prize but the winners do get a certificate and are invited to present a synopsis of their paper to their peers. All of the entries are eligible to be published in the ICE book.

Figure 1 – Technical Papers Competition Timeline

3. Incentive to Participate

3.1 How difficult was it to establish?

Due to the nature of the project, and the professionalism established within the project, many of the employees and contractors are/were/became experts in their fields. As such, their knowledge and expertise was sought after by the professional bodies and the construction industry. Also, in order to build and enhance their and their companies’ reputation individuals were keen to promote the knowledge gained on the project to share the knowledge and innovation being developed. Therefore the technical papers competition provided an ideal opportunity to promote what teams and individuals were doing and a channel for how to do this, set up with clear rules and guidelines.

3.2 Finding Contributors

The competition got off to a good start, in that, the very first competition generated 36 papers. It also provided the project with a means of channelling all the requests for technical papers and journal submissions through an established mechanism which kept the requests manageable and provided participants with a structured process. A further benefit was that it then allowed the participants to use the paper as a basis for any subsequent requests for information, and although the papers had not gone through a formal external review, there was an independent peer review process and it also gained professional body recognition through being published by the ICE.

The guidelines for the competition also allowed “teams” to contribute a paper, not just individual authors, so employees and contractors who had worked together on specific areas of the project were encouraged to collaborate and enter a paper to the competition.

3.3 Maintaining Contributions

Once the competition had been established and the first book published “word of mouth” was a big contribution to the promotion of the competition. The book publication caught the imagination and contributors were given licence to do whatever topic they wanted, given the fairly broad guidelines. This led to a real enthusiasm to take part even though it was all essentially in addition to the “day job” and an in-depth technical paper.

3.4 Book publication

By arranging with the ICE that the papers would be published in book format there was a great incentive to encourage participants to enter the competition. Crossrail agreed the format with the ICE, A5 , black and white print, and agreed to pay for a set number of books to be published. It was a limited publication run but Crossrail would receive 100 books and the ICE would promote and sell the remainder through its publication arm. A number of copies of the Crossrail allocation were distributed to the authors of the submitted papers. The total cost for producing the books was negotiated and agreed at a fixed cost which has remained consistent.

Figure 2 – ICE Book Publications 2013-2017

The editing of the papers was carried out by the organising members of the Chief Engineer’s Group and the papers were then provided to the ICE for publication in black and white and with a Crossrail approved cover design.

As the papers moved from mainly civils through to mechanical and electrical fit-out, working with other institutions for the book publication was explored, but the appetite for producing the books by bodies such as the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) or the Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) was not strong. To them it was an unknown, high risk sell and not guaranteed to be attractive to their members. As the ICE were quite happy with the arrangement, and as it had worked very well , the publication of the book remained with the ICE throughout, even with the slight shift of focus of the topics.

4.0 How has the Competition Evolved?

Due to the strong governance and structured rule system from the start, the competition has stood the test of time. The format has remained constant throughout and the only difference has been that the topics covered have evolved as the project has progressed. The initial papers were very much civils topic papers but that has gradually changed into mechanical and electrical topics.

It is still very much an engineering led competition, but all the papers have now been incorporated onto the Learning Legacy website which was developed by Crossrail to disseminate the learning from across the whole project. Engineering is now one of 12 themes that have captured insight and knowledge from across the project. The bulk of the content in the engineering theme is made up of the technical papers.

In essence the TPC was the forerunner of the learning legacy programme and captured all of the early engineering expertise and knowledge. Seeing how well this could be done fed into the development of the different types of papers for the learning legacy and along with learning from other major projects such as London 2012, gave it a good basis from which to start.

5.0 Why is it popular?

When it was introduced there hadn’t been anything quite like it in the industry before and it was well received internally and externally. Involving the engineering expert panel in the process was a key element as it provided independent expert peer review for the shortlisted papers. This provided total credibility and a level of professionalism immediately acceptable by the professional bodies.

This, in turn, ensured accurate and high level papers providing peer group recognition and a great opportunity for self promotion as well as shared recognition among the teams submitting papers. Junior members of staff were encouraged to get involved providing good team working and sharing of knowledge at all levels.

Figure 3 – TPC Award of Certificate and Presentation evening at the Institution of Civil Engineeers

6.0 Learning from the Technical Papers Competition

Establishing the Technical Papers competition was a good way of capturing lots of papers on many aspects in one place. Due to the nature of the industry, many people belong to professional bodies and naturally are looking to establish their own careers and reputation. In order to do this, creating technical papers for conferences and journals is par for the course. However, permission is, of course, required from the projects being worked on and ideally the papers need to be vetted to ensure accuracy and reliability. The reputation of both the Company and the individuals are at stake. The TPC provided a channel for people to create papers that were “approved” internally and could be used for knowledge and insight about the project, as well as being published by the company in conjunction with a professional body. It reduced the spurious requests internally for “checking/vetting” papers and provided a high level reviewing system that included external reviewers in a manageable format.

6.1 Key Overall Lessons Learned

There were a number of things that have been identified as contributing to the success of the competition

- The sequence of books was ordered logically – starting with design/planning and gradually moving through construction, fit-out and systems matching the corresponding stages of project delivery. This in fact happened by chance. Therefore it would be prudent, if possible, to plan some of the content.

- The mix of discipline topics within the books reflects the number of different activities ongoing during delivery

- The competition is quite difficult for people to fit in as well as the “day job”, but they do recognise the benefits and “kudos” it can bring. Being hard to do, contributes to the credibility of the competition aspect and increases the sense of achievement when completed

- Providing clear rules and guidelines from the outset maintained the consistency

- It can be difficult to moderate but this ensures a high level is achieved with the papers submitted

- Judges decisions were never challenged which justified the formal structure and the marking criteria was clearly defined

- It was important not to give “prizes”. It was decided early on that recognition of being a “winner” or “highly commended” would be to present your paper to your peers and do a Q&A session. All accepted papers would be included in the book publication (with an opportunity to improve, if required) and this was a huge incentive to take part, knowing that you could be “published” by a top professional body as a reward.

- Transparency and the ability to include negative as well as positive aspects of the topics if appropriate. To encourage learning, and for it to be useful to other projects, both positive and negative aspects need to be discussed.

- A key part of an Engineers Continuous Professional Development (CPD) is required by the Engineering Council to maintain the status of a Chartered Engineer. These publications add to the evidence required.

- In effect it was a pre-cursor to the now established Learning Legacy process. Knowing that a formal, structured process could work so well it provided good learning and a good basis for taking the idea of a Learning Legacy project-wide.

6.2 Lessons Learned from the Competition Process

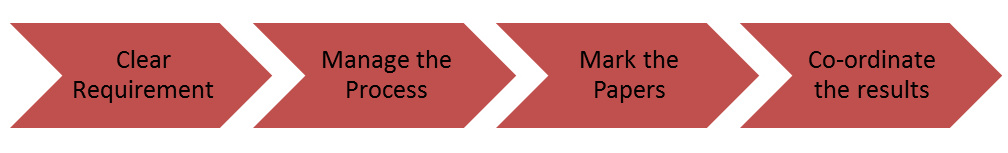

The competition process is quite simple and can be summed up by being clear on the requirement, putting in place a structure to manage the process, getting the papers marked and co-ordinating the results and presentation.

Figure 4 – Technical Papers Competition Process

To execute that effectively:

- Call for abstracts early

- Accept/reject the abstracts within a short turnaround period

- Ensure you have the appropriate number of reviewers – this depends on the topics covered and number of papers submitted. Eg. Typically 40 papers – could need anything up to 12 people to mark depending upon the range of disciplines covered. Then you require 3 or 4 people from marking panel to moderate

- A process co-ordinator is needed to enforce deadlines, manage participants and manage the markers

7. What could be improved?

On such a large infrastructure project there was, and still is, lots of good learning that can be captured.

The majority of the authors were from Crossrail, although there were some very good collaborative papers. Bigger and more comprehensive advertising of Technical Papers Competition could have been done to encourage more participation. Efforts were made to encourage designers and contractors to submit papers, as getting a wide participation was part of the original idea, but that communication could have been developed further to generate greater contractor involvement. Designers were keen to promote what they did as they saw it as beneficial to their reputation, but there was some reticence on the part of contractors to share new learning. It may be that if something new and innovative was done, the contractors wanted to be able to keep that knowledge or use that as leverage for other contracts rather than widely share and promote the development.

The challenge would be to try and encourage contractors to promote any advances or developments so that the industry gains or improves as a whole but, at the same time ensure it is still attributed to them.

Within the rules and guidelines a further addition could be to get a short author biography and photo if promotion of the authors is or becomes part of the remit, as happened with the development of the Learning Legacy website.

8. Conclusion

The technical papers competition so far has generated four volumes of papers published by the Institution of Civil Engineers (117 papers), with the competition already in train which will generate the papers for a fifth volume planned for 2018. Each volume contains at least 25 excellent papers on various aspects of the Crossrail project. Volumes one-three mainly focused on the civils aspects, volumes four and five moving onto the mechanical and electrical aspects as we move into the latter stages of the project.

Having this opportunity to provide an insight into the project, and the “kudos” it provides for the authors, provides a tangible outcome and a well respected and enduring learning legacy.

Being able to provide all this information and insight to the industry using a robust and timely process, utilising the people actually working on the project, was an excellent way to capture useful and insightful learning that can now be used in future projects. It also provides those that have taken part, a tangible demonstration of what they have been involved with, and have worked on, that they can take with them and provide to others when moving to the next project.

The papers are now included on the Learning Legacy website and therefore it is questionable whether a book publication would be considered in the future. Technology makes the papers more accessible, but the idea of having a paper printed in a tangible format by a professional body is still a compelling incentive for the authors of the papers. Therefore the book publication should still be a consideration if implementing a similar type of learning legacy competition in the future.

-

Document Links

-

Authors

Mike Black BSc(Hons) MSc CSci CGeol FGS - Crossrail Ltd

Mike is the Head of Geotechnics within Crossrail’s Chief Engineer’s Group. Mike’s role is to provide technical and professional leadership for all geotechnical aspects for the tunnelling and civil engineering sub-surface infrastructure work. He has been on the Crossrail Project since 1993 and has been involved in all stages of development of Crossrail from feasibility design, through the Parliamentary Bill process, ground investigations, civil design and construction. Prior to joining Crossrail, Mike worked in the oil and gas industry in the North Sea, the Channel Tunnel, the A27 Brighton & Hove Bypass and the Jubilee Line Extension.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/mike-black-4aa9b81b?trk=hp-identity-name

Brigid Leworthy DMS MSc MIET - Crossrail Ltd

Brigid is currently the Crossrail Learning Legacy Co-ordinator bringing together much of the content on the website and co-ordinating liaison with the Learning Legacy partners. Brigid trained as an engineer and then moved into project management. She has worked for a number of large organisations including BT, the London Fire Brigade, The British Red Cross and the University of East London. She has a postgraduate Diploma in Management, a Masters degree in Project Management and is a qualified PRINCE2 practitioner.