Transitioning of the engineering management in the handover phase of programme delivery

Document

type: Technical Paper

Author:

Lukasz Pasieczny, Paul Readings IEng MPWI

Publication

Date: 02/12/2021

-

Abstract

The Engineering Management Office (EMO) function provides an important link between the client’s specifier of requirements and its contracting arm delivering the works. The longevity, scale and geographical fragmentation often necessitate a phased completion approach in delivery of major infrastructure programmes. Nearing the completion point brings pressures of schedule and cost and demands changes in the organisation and approach of EMO. It is an acquired leadership skill to recognise the need early, to reap the long-term benefits of engineering knowledge retention and ultimately its transfer to the end user.

In this paper we present a model set-up and timeline for deployment of a transitional engineering team. We introduce the workings of an engineering integration task force, whose success became a blueprint for that transformation. We set out guiding principles of workings, moving away from a vertical to more horizontal representation across the programme. We also draft a pathway for embedding the residual engineering team in the Infrastructure Manager’s organisation.

The findings will inform long term strategies for transition of engineering knowledge and resource planning for handover phases of major projects and programmes.

-

Read the full document

Introduction and Industry Context

For large infrastructure projects the handover date is a phase, not an event. The value received by the client organisation can be greatly enhanced by, amongst other, transfer of knowledge and a meaningful aftercare.

Association for Project Management’s recent research paper on improving handing over of projects[1] briefly focuses on knowledge transfer, in a form of documentation and training. This case study enhances that learning and proposes a model change, implemented within Crossrail’s (CRL) Technical Department, enabling retention of people and skills needed post-handover. The nature of Crossrail project makes this paper particularly relevant to large-scale programmes, new or upgrade metro construction and mainline railways, as well as linear infrastructure projects in energy, water and transportation sectors.

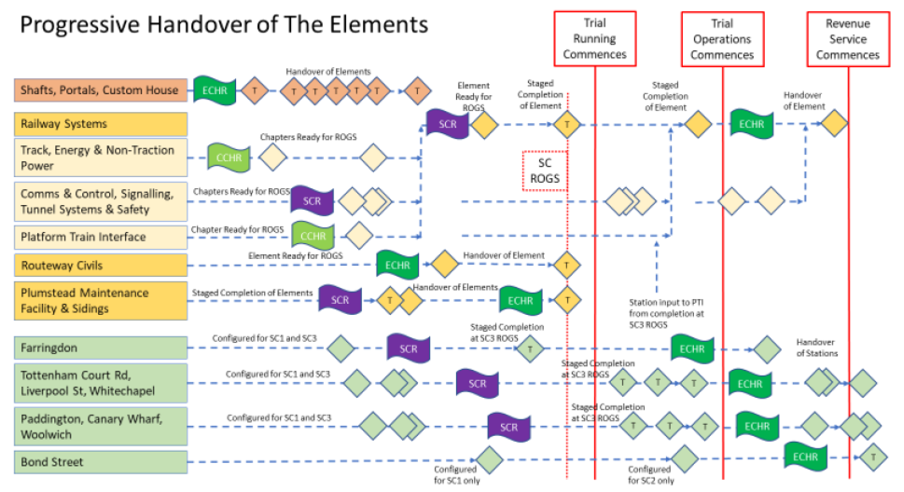

CRL Handover Strategy[2] sets out the path to transfer the Central Operating Section – the railway and stations in twin-tunnels under Central London – to the relevant Infrastructure Managers (IMs). It pivots around 30 Elements – integrated but distinct, location or system specific building blocks of assurance. Due to sheer scale and effort needed on the receiving end, those Elements are not being handed over all at once but are staggered instead, see Figure 1, and is captured in the CRL Migration Plan[3].

Figure 1. Sequence of Element Configuration, Staged Completion and Handover[2]

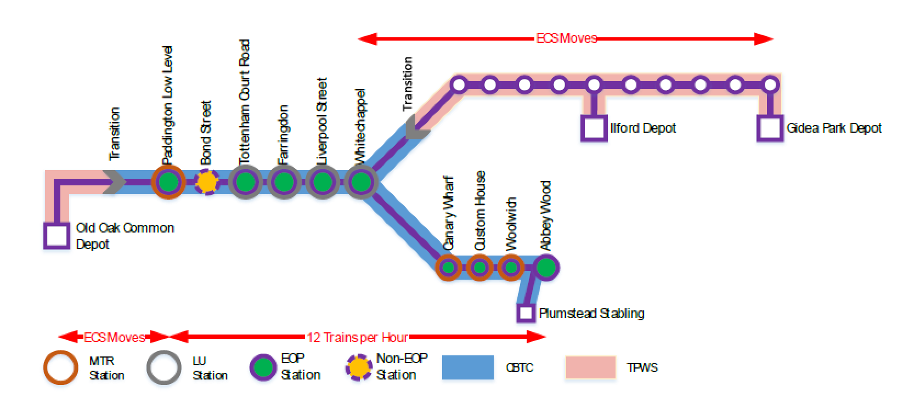

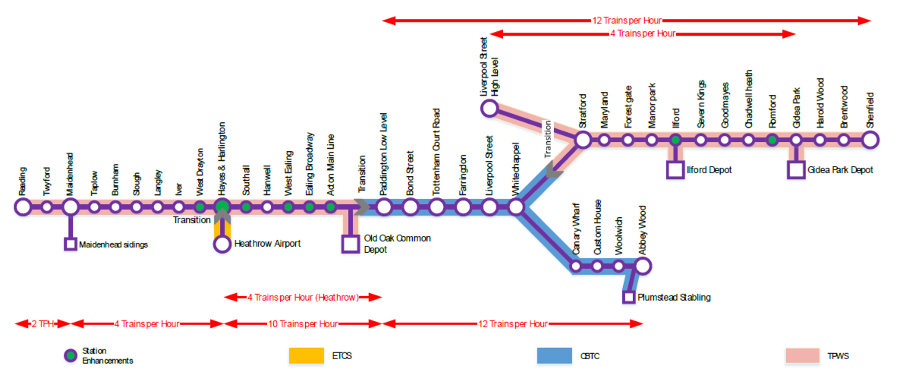

Figure 1. Sequence of Element Configuration, Staged Completion and Handover[2]Consequently, Crossrail’s opening stages and configuration states, Figure 2 and 3, coincided with staggered commissioning and handover activities for Stations, Shafts, Portals (SSP) and of the Railway Systems (RS), testing of fringe connections to the existing mainline railways in the East and West, with iterative integration of the Rolling Stock took place in Dynamic Testing (DT). This was further compounded by operational needs of IMs, trial running the infrastructure and its reliability, whilst train operators were practicing safety and emergency procedures.

Figure 2. Stage 3a with Central Operating Section open[3]

Figure 2. Stage 3a with Central Operating Section open[3] Figure 3. Stage 5b West to East railway opens[3]

Figure 3. Stage 5b West to East railway opens[3]Whilst all this would have been anticipated at the outset to an extent, the schedule focused on completion of construction and the newly appointed IM was gearing up to run the steady-state, finished railway.

Above all, the programme was experiencing pressures of a limited funding envelope, political and public scrutiny on the schedule and ongoing costs. An alternative delivery of some of the remaining scope by the existing operators now being considered with its own risks imported.

Team 30

Where it all began

The need to provide calm, stability and continuity became paramount and it came from the EMO. A function of the Technical Department, it provides an important link between the client’s specifier of requirements and its contracting arm delivering the works. Functionally reporting to the Chief Engineer since 2012, the line management was to the Delivery project managers per site. In 2019, in response to the growing quality issues, the EMO was created, bolstered, and brought together under the Technical Director. Its historical presence and position within organisation made it well placed to secure the engineering legacy to the IM and provide stability during the transition.

Team 30 – model set-up

The EMO recognised in summer 2020 the need to transition into a different model, fit for reality setting where Crossrail is no longer a construction project with test trains running through it, instead it being a “third party”, working along an operational, regulated railway. Predominantly interacting with the Train Operating Company and Infrastructure Managers, the organisational set up and means of working would have to reflect the new circumstances. Focus on the immediate programme pressures soon would have to be aligned with new regulatory requirements, with works delivery, engineering safety and assurance to follow suit.

Nine months prior the scheduled Entry into Trial Running (EiTR) in April 2021, discussions about the transition began, within a month the outline was ready for a wider Technical Directorate briefing and it was soon conceded by the CRL senior team that the concept was a suitable model to consider for broader Crossrail transition.

Figure 4. Guiding principles for the transformation

Why

The idea of Team 30 – name reflecting a foreseeable size of the engineering team being transitioned into the IMs – was built around the premise of ensuring the new railway continues to be fit for purpose and meets requirements through engineering excellence.

Borne out of passion to deliver the Elizabeth Line, the reasons centred around securing the Crossrail legacy, determination to meet the requirements, ensuring continuity of knowledge and experience of CRL Engineering throughout the transition from a construction programme into the operational railway. Effectively doing the “right engineering thing”, in response to the risks brought about by the programme pressures.

Rapidly approaching EiTR would soon become the first opportunity to test the effectiveness of the proposed new set up, as the projected cliff-edge drop in resources would impact otherwise still active multiple Crossrail sites. Transition of engineering resources over a period of six to nine months was needed, before reaching the “end state” form of the Team 30.

How

For that purpose a consultancy model, offering specialist services across the programme, was chosen and the Professional Engineering Services (PES) was created. Working across the entire project and not tied to location or delivery contracts, the flexible multi-disciplinary team of specialist engineers could be dispatched as needed.

What – benefits

The vision of the Team 30 set the direction for a controlled phase out of transient workforce, focusing on the long term retention of the skills and expertise within Transport for London, needed to resolve problems already foreseeable at this final stage of Crossrail.

The fundamental benefit to the Elizabeth Line of transitioning to the Team 30 was the retention of skills and knowledge within CRL in the short to medium term, and a controlled transfer of those to the IMs in the long term. This changeover would:

- support systems integration across the final configuration states of the project

- deliver a legacy of Engineering excellence, realising improvements, and implementing lessons learned

- building on experience gained from one phase and applying to the next

- championing collaborative working between Crossrail and the IMs, enhancing what has been achieved already, under the “one team” approach

An important task set for the team was to improve clarity on responsibility and accountability for delivery engineering roles in the shifting landscape.

In practical terms, the objective was to manage the close-out of outstanding works and assurance activities in an efficient and timely manner. Put simply: spending less, in a controlled manner, to deliver more where and when needed.

Within these parameters, Team 30’s matrix set up included three Engineering Leads to cover MEP, Rail Systems and Civils disciplines, with 25 “consultants” providing pool of resource across the following areas:

- Engineering Management

- Field Engineering

- Supervisor Representative

- Discipline Assurance

- CAD Assurance

- Specialist Advice and Support

Sizable, nimble group of engineers was designed to lead the charge on closing unfinished and those foreseen-but-yet-unknown activities. Bringing owners, operators and maintainers along, aligning all to the programme close out strategy, would translate to sizable tasks for the team to manage and deliver.

Pathway to Team 30

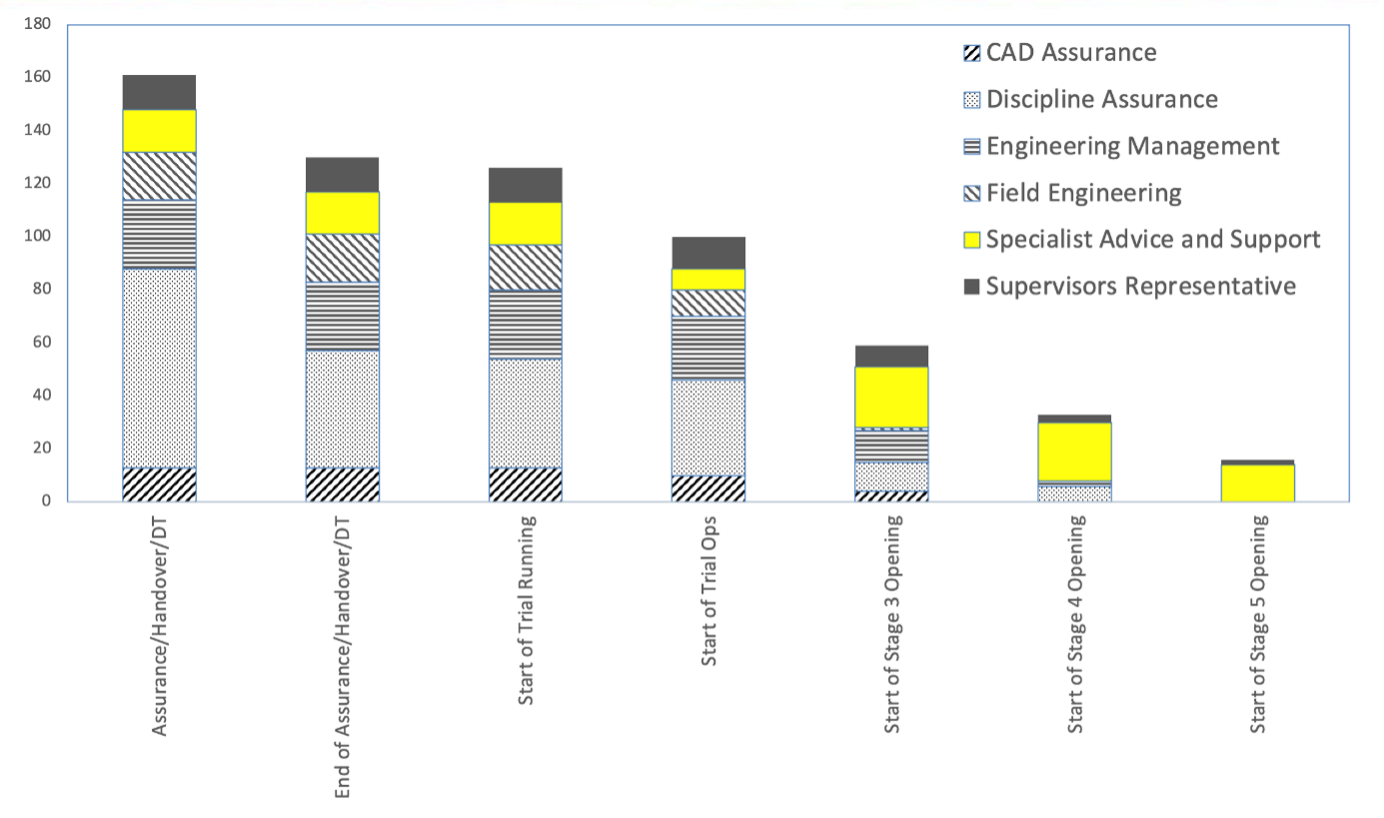

To become viable, this business proposal had to be underpinned by a careful workforce planning. In summer 2020 over 180 engineering roles were filled full time, not tied to otherwise shifting delivery milestones. To counter this, posts were fixed to key dates and internal transfers within PES were forecast in principle over the next 12 months, spanning over key opening stages, see Figure 5 below.

Figure 5. Forecast transition to Team 30[4]

Figure 5. Forecast transition to Team 30[4]It well indicates the reduction of PES staff to match the needs of the programme, to enable the retention of knowledge and expertise to complete CRL’s project and transition to the Elizabeth Line.

The more evident risks considered at the time were:

- retention issues from lack of longevity

- novelty now gone, burn out

- competing opportunities (i.e. High Speed 2)

- HR / IR limitations

- binding arrangements and ongoing costs of framework suppliers and programme partners.

These have been overcome and at the time of writing (August 2021) the majority of Crossrail assets – the railway and SSP – have been handed over to the end users. Nevertheless, the PES team still stands at 96, reflecting strong engineering presence needed post-transfer of assets. Crossrail’s experience indicates an average lag of four to six months, before reducing engineering to minimal level, feasible only to assist with contractual close out of contracts. See Table 1 showing numbers for 26 key Elements, adjusted for time lag between handovers. Note the average numbers are skewed by teams responsible for multiple but smaller Elements, those being handed over across longer period.

Peak Handover H + 3months H + 6months Total 120 118 80 54 Average 5 5 3 2 Table 1. Engineering management presence at peak and after handover. Average per Element

PES resourcing being discussed weekly is indicative of the responsiveness of the team to the business needs. Ability to now share the Supervisor Representative’s time between Shafts and Canary Wharf Station or short notice replacement of Paddington Station’s leading engineering role can be easily translated into eight weeks of programme delay mitigation – a significant saving of prolongation costs. Similarly, flexibility to move Lead Field Assurance Engineers supported the aggressive stations handover schedule of 2021.

For implementation of the mechanics of Team 30, adopting and scaling up the tried and familiar Tiger Team model – covered below – was a natural choice.

Tiger Team

History and original purpose

As Crossrail’s handing over of “nursery”, early transfer Elements to the Rail for London Infrastructure (RFLI) concluded in August 2019, a need for a roving task force has been identified and by November 2019 a team of eight engineers was stood up to start this process. With Elizabeth Line scheduled at the time to become a regulated railway in September 2020, this additional resource focused on the Railway Systems handover, in particular closing out the Element’s Outstanding Works Lists (EOWL) and project technical requests (PTR), still counted in thousands.

After the initial successes, the sheer scale of the EOWL / PTR task was re-assessed. The team was unable to make a meaningful impact in the performance graphs and resistance towards an external assistance was increasing. That’s when the task force was put firmly under direct leadership of the Head of Engineering, with experienced engineering and transformation individuals added to the team. A pivotal move, as the Tiger Team – an informal name given at conception, which stuck – now had senior backing, was at last given a clear purpose, ways of working, organisational structure, visibility across the programme and buy-in from key stakeholders.

New approach

The transformational, now formalised qualities of the Tiger Team were based around the following four characteristics:

- leadership’s vision of “act fast, fail fast, learn fast”, a guiding principle of moving fast to solve a problem but not worrying if it fails as quickly, as it will stop the pursuit of a non-performing approach and allow learning from the failure. This concept is based on LEAN – a management method aimed at improving performance and also features in IBM’s Garage Methodology[5]

- value-adding being the deciding factor for team’s engagement. With limited resource and vast demands of the programme, becoming a “body shop” was not an option

- flexibility, not being anchored to a single location / contract or engineering discipline

- composition: being self-contained, able to identify programme-wide issues, tenacity to promote the action, capacity to bring the work in and to see issues through to conclusion.

Characteristics

The Tiger Team constituted from engineers with the following background: two electrical and two mechanical, one civils, one rail systems and an engineering safety specialist. A mixed pool of skills and abilities, when considered and deployed as a team, were able to challenge their limitations, with individuals’ boundaries stretched to their benefit. It must be recognised that positioning within EMO gave the team access to the body of knowledge and skills already existing within the Technical Directorate. All above was crucial to its success as it allowed the team to take on and manage a broad spectrum of engineering integration workstreams.

Following from this strategic review, the original task of Tiger Team was enhanced and split into six number of workstreams. The potential seeds were now selected based on:

- the programme-wide nature of open EOWLs

- struggles noted during early Elements’ handover

- immediate needs from the Head of Engineering or the Chief Engineer

A multidiscipline approach was formed and the ideal of being more flexible was devised, which became known as the swiss army knife approach. The new modus operandi transformed the team into a well performing, responsive task force, continually aligning to the changing short and long term programme priorities. The team quickly learned that under-resourcing of teams or overstretched programme targets were outside its zone of influence and had to be dealt with by the organisation’s existing processes.

Implementation

Team 30 – timeline and context

With a scaled-up Tiger Team setup seen as a suitable blueprint for the Team 30, the transition continues at the time of writing. Table 2 below summarises the key events covered in this paper, indicating it took three months from inception, through to consultation and implementation of the new structure, with a formal announcement delayed by three months, to align with the key milestone of EITR and clear the HR / IR processes.

Date Event Engineering Management Tiger Team Aug 2019 Handover of nursery Elements – Nov 2019 Tiger Team created 180+ 8 Aug 2020 Team 30 idea Oct 2020 Shafts and Portals handed over 180 10 Nov 2020 PES created 160 Apr 2021 Railway handed over (EiTR) 120 8 Aug 2021 Most Stations BIU / handed over 96 7 Nov 2021 Trial Operations commence 47 (f) 3 (f) Mar 2022 Stage 4 opening (Team 30) 34 (f) – Table 2. Timeline of engineering resource reduction, including forecast (f)

Key points so far

Reflecting on Table 2, the impact pandemics had on the overall programme is clear, with an estimated six months’ prolongation on transitioning the engineering capabilities to the Team 30.

Planning for such transition on projects of similar magnitude and state of completion, it is recommended that:

- around three months are needed to promote, consult and deploy the new structure

- existing engineering resource can be reduced around each handover date, but core knowledge needs to be retained for six months beyond that milestone

- understand personal aspirations to successfully retain desired “Team 30” mix, for some Crossrail engineers the journey has now been over 12 months long

- human resources need to be understood and carefully managed at the earliest

Lessons learned

In addition to the above, the following two areas were seen as valuable learning points, to be recorded in this paper:

Team 30 – inception to “go”

- It is an acquired leadership skill to recognise the need early, to reap the long-term benefits of engineering knowledge retention and ultimately its transfer to the end user. Treat project experience, knowledge of past issues as “gold dust”. Same for good working relations with the end user.

- Acknowledge there will be issues that will need resolving beyond bringing into use, recognise and record this early as a risk. Inception, consultation & implementation takes time.

- Being ahead of the curve brings opportunity to shape the transfer of knowledge and securing legacy, at the same time can be challenging. This needs open communication channels to the senior leaders.

- Change overload will diminish the confidence of the business, stakeholders, and the team. Plan the internal and external communications at the outset.

Tiger Team – processes, tools, people

- Avoid temptation to fill “resource gaps” within the programme, as those diminish both flexibility and responsiveness of the team. Clarity of purpose – those guiding principles – makes it easier to reject non-value adding workstreams.

- The most effective tool used by the Tiger Team was perseverance. The other was simply being an independent party in the room, which brought out behavioural changes to the conflicted sides.

- Reshaping the team is unavoidable and resourcing on large programmes take time. Get it right first time, request for specialists to meet the vision and mission. Secure long-term commitment from individuals, supply chain and PMO, thus reducing staff rotation and wasted time. Bring HR team along the journey and, if possible, arrange for internal transfers from the end user organisation.

- Above all, do not be afraid to take the initiative and if needs be adopt the ‘Act Fast, Fail Fast, Learn Fast’ approach presented here, and then improve, learn and move forward.

Recommendations for improving Future Projects

Even with a “big bang” planned, the handover will be a phase, with residual works to deal with afterwards. This transition needs early recognition as a risk to legacy.

When planning future projects, the tangible benefit of long-term retention of engineering team beyond the bringing into use should be acknowledged in the Corporate Management System, intentionally transferring in some capacity to the end user. Any such arrangement should be aligned with responsibilities and accountabilities within the IM’s Safety Management System.

This paper indicates roles, costs and durations of residual team and allows for funding to be set aside and included in resource loaded programme with high certainty. It is also recommended that a central services planner is designated to Technical Department, to support such transition.

The model presented herewith can be easily adopted and as shown, is scalable. Early trial of a small-scale team, with the end goal of Team 30 in mind, will allow retention of valuable resource.

Whilst at the time of writing this paper the discussion on embedding the Team 30 in the IM’s structure is ongoing, it is intended to retain its identity, to provide structure, scope control, reporting and monitoring prior to final conclusion.

Conclusion

This paper recognises the domain knowledge that projects close-out may extend years after brining facilities into use and proposes a viable means to alleviate factors which may otherwise lengthen that period, impacting long term benefits of the new infrastructure.

Advice to similar projects would be to, armed with this knowledge, be prepared and be ahead of the game, actively addressing the transition issues.

Acknowledgements

Susanne Barber, Paul Pruszynski and Toby Ward for helping to shape the PES transition.

References

[1] Owen Anthony, “How can we hand over projects better”, Association for Project management, July 2017

[2] Crossrail’s Project Handover Strategy & Plan, Central Operating Section, CRL1-XRL-K1-STP-CR001-50001 Rev 6

[3] Crossrail’s Migration Plan, CRL1-XRL-O8-STP-CR001-50166 Rev 2

[4] Delivering PES presentation

[5] IBM Garage Field Guide, https://www.ibm.com/cloud/architecture/files/ibm-garage-field-guide.pdf

-

Authors

-

Acknowledgements

Susanne Barber, Crossrail

Paul Pruszynski, Crossrail

Toby Ward, Crossrail