The Appraisal and Business Case for Crossrail

Document

type: Micro-report

Author:

Paul Buchanan

Publication

Date: 13/03/2018

-

Abstract

The Business Case for Crossrail developed along with the evolving scheme during the period until the Crossrail Bill was submitted, and was revised in 2010 alongside the Comprehensive Spending Review. Several innovations were incorporated most notably work to establish the Wider Economic Benefits of the scheme. This report gives an overview of the process and the development of the Business Case. It will be of interest to project sponsor organisations.

-

Read the full document

1. Introduction and Industry Context

Major project funding and decision making bodies decide whether to proceed with projects informed by a business case, which will include an appraisal of the costs and benefits. The business case for Crossrail developed significantly as the project moved towards a decision to proceed and led to some important innovations and changes to the way major transport schemes are appraised.

The Crossrail project has been in development for a long time. The first version for which costs were identified was that in the London Rail Study of 1974[1] with a predicted cost of £300m. The Central London Rail Study (CLRS) of 1989 (Figure 1) put Crossrail at the top of its “To Do” list of 3 schemes with costs of £1.4bn and a Benefit-Cost Ration (BCR) of 1.6:1 however the only scheme to proceed at that time was the Jubilee line Extension because 1994 saw the Crossrail Bill (submitted by London Underground and British Rail) rejected by the Commons Bill Committee. Private Member’s Bill Committees do not necessarily state reasons for finding against the principle of the Bill but the main reason seems to have been the expectation of a continuing decline in central London employment which had begun after the CLRS was published.

Figure 1 – The Central London Rail Study (1989) and London East West Study (2000)

By 1996 London Transport and the Department of Transport reported a BCR of 1.7:1 for Crossrail. That may not seem amazing in the present day, but with a discount rate of 8% per annum a high BCR for a major rail project was extremely difficult to reach. Discount rates are now 3.5% which increases the value of benefits considerably. The conclusions of the joint study were that Crossrail was a reasonably good project in economic terms but an expensive one with a significant construction cost risk. It was the London East-West Study published by the Strategic Rail Authority (SRA) in 2000 which prompted the Government to call on the SRA and Transport for London (TfL) to set up a joint company, Cross London Rail Links (CLRL) to promote the scheme.

2. Appraisal of Crossrail

In November 2001 CLRL appointed Colin Buchanan and Partners to work on the economic case for the project which started as a traditional static cost:benefit appraisal. The base case and a number of alternative alignments and branches were studied. The modellers ran tests through TfL’s London Transportation Studies (LTS) model to produce the user benefits. Outline cost estimates with appropriate contingency were prepared by the engineering team.

The scheme for the 1993 Bill had two branches to the west and one to the east. This was because the Shenfield line to the east could fill 24 trains per hour (tph) but the Great Western line to the west could only accommodate 12-14 tph so a second western branch was needed. For the new scheme options to Amersham, Aylesbury and, as a later addition, Richmond were all tested. It didn’t matter too much to the case which one was chosen, once the capital had been spent on the main tunnel and central stations all the branches showed very high returns. The key was to maximise the use of the central tunnel.

The main appraisal issues were:

- Using a London Value of Time, rather than the national average. The Department for Transport (DfT) preferred geographic equity with the same value of time everywhere. A Crossrail value of time based on the characteristics of Crossrail users produced a value higher than the London average and the DfT then agreed on using the London average value.

- Revenues – LTS is an AM peak model with no fare zones. Revenues were calculated on the basis of passenger kilometres and annualised as usual. However when the station at Whitechapel was added to the model for the original scheme revenues rose based not only on the station but on the increased length of route. This needed to be recognised and accounted for.

- Heathrow – This was always a complicated part of the network to model. Values of time were very different as was willingness to pay higher fares. Choices between Heathrow Express, Crossrail and the Piccadilly line could not be done in Railplan/LTS but used a bespoke Heathrow model.

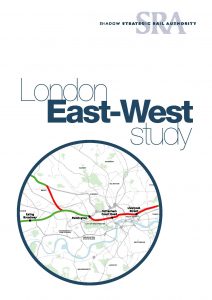

The Business Case presented in July 2003 had a BCR of 1.99:1 for the 2003 ‘Preferred Route’ (Figure 2). The scheme, as revised following the Montague Review in 2004 and submitted in the Crossrail Bill, had a slightly lower BCR of 1.8:1 largely due to the decision to terminate the south eastern route at Abbey Wood, rather than Ebbsfleet. While that decision removed technical complexity, and therefore cost, by enabling the whole line to use overhead electrification and rolling stock not to allow for dual voltage, it also reduced the passenger benefits and revenue from the longer distance services. 1.8:1 was still within the range of ‘medium’ value for money defined in DfT guidance where the guidance states that ‘some, but not all’ projects should be taken forward.

Figure 2 – 2003 Preferred Route

3. Wider Benefits work and the Case for Crossrail

The lasting legacy of the Crossrail appraisal however was not the standard transport appraisal but the development of Wider Economic Benefits (WEBs). The push came from the Greater London Authority and Mayor’s transport team who wanted to understand the impact of the project on central London’s economy. That question started off an intense 18 month period of work and the development of a new approach to valuing transport infrastructure, which is now being applied not only in the UK but around the world.

The essence of the argument was that transport capacity posed a constraint to central London employment growth. It was clear that to deliver the London Plan growth forecasts[2] significant additional capacity would be required. While there was (and is) strong demand from employers to locate in central London, from developers to build new commercial space and enough areas with supportive planning policies to accommodate expected growth, without the transport capacity it wouldn’t happen.

However the transport models were of no help in this respect, as they assumed that all passengers can always board the first train irrespective of the level of crowding with no capacity constraints on either buses or trains.

That led to extensive research on:

- How crowded trains could actually get in practice

- Analysis of when crowding levels stopped growth in demand

- Testing of an alternative “crowding curve” with much higher penalties for very high levels of crowding

The next question was “is it worth it?” Why should we spend a lot of money in order to accommodate growth in central London rather than elsewhere? The answer turned on productivity. Central London had and has productivity levels roughly double the rest of London and at least double the UK average. It is that productivity differential which makes it worthwhile investing to overcome the transport capacity constraint on growth. It also means much higher tax returns to HM Treasury than for comparable cost schemes elsewhere.

Formalising the approach to the satisfaction of the many government departments and regulators involved proved to be a lengthy and complex exercise. The transport authorities were unanimous in their suspicion of any change to the existing approach to economic appraisal, but the Treasury were supportive and interested in a case which linked infrastructure to economic performance rather than user benefits. A Wider Benefits Working Group was established with representatives from the key organisations and concluded that the agglomeration impacts were both substantial and entirely additional to any benefits valued using the standard static cost:benefit appraisal approach.

DfT guidance on WEBs was issued in 2004[3]; by that stage Crossrail was claiming WEBs of £10-15bn, broadly equivalent to the value of all the user benefits.

4. Economic Impact Assessment

The other main area of work during the development phase was the economic impact assessment which considered the impact of the implementation of Crossrail on local facilities and businesses and formed a key part of the Environmental Impact Assessment. The Specialist Technical Report to the Environmental Statement is available here.

5. The Sponsor Business Case

The project Sponsors, TfL and DfT, made two updates to the Business Case after CLRL had been reconstituted as Crossrail Limited to deliver the scheme. The first was related to the Mayor’s 2010 Transport Strategy[4] and the second revised the costs and revenues after the project had been reviewed in the 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review[5] and the funding envelope reduced from £15.9bn to £14.8bn. The summaries of the updates along with work undertaken in 2009 to demonstrate the distribution of the benefits of the scheme across London and the South East are published in the Learning Legacy document Crossrail Business Case.

6. Learnings and improvements to appraisal guidance

Only a major project could have accommodated the research that was required to make the case for Wider Economic Benefits, a succession of smaller projects would never have been able to make that investment. There is a fine line between economic appraisal and advocacy but WEBs are now approved and applied in many countries around the world. The Elizabeth line will be in full operation in December 2019 and it is expected that it will deliver on its demand forecasts and enable further employment growth within central London. Beyond this the legacy of WEBs globally will hopefully ensure better decision making on major urban transport projects and policies.

References

- http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C11076049

- https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/london-plan/past-versions-and-alterations-london-plan/london-plan-2008

- https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/556077/webtag-wider-economic-impact-appraisal-tag-unit-a21.pdf

- https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/transport/transport-publications/mayors-transport-strategy

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/spending-review-2010

-

Authors

Paul Buchanan - Volterra

Paul Buchanan is a partner in economic and transport consultancy Volterra.