Crossrail Art Programme

Document

type: Technical Paper

Author:

Robert Wood BSc(Hons)(UCL) DipArch(Cantab) RIBA L’Ordre des Architectes Francais D&AD, ICE Publishing

Publication

Date: 03/11/2014

-

Abstract

The Crossrail Art Programme has developed since this paper was written in 2011, in particular with the establishment of the Crossrail Art Foundation with financial support from the City of London Corporation.

At the heart of the Crossrail project is a commitment to support London’s position as a world-class city by delivering “a world class railway that is fit for the 21st century.”*

The construction of Crossrail is an immense feat of engineering, which will transform the city’s congested streets. But it is also a project of great cultural significance, with the potential to transform the world’s view of London.

London is a city of culture. It understands that ‘culture’ is a complex mix of art, business and the wider social realm that forms a tangible asset, which can attract inward capital investment, tourism and the world’s most talented people and successful companies. The design and construction of a new railway in the heart of London presents a major opportunity for a new cultural programme that can dramatically increase the regenerative force of Crossrail.

The golden era of London Transport, under the stewardship of Frank Pick, showed how public art can help to enhance the passenger journey experience, improve the public realm, forge engagement with staff and local communities and encourage ownership of a network.

This paper discusses the creation, development and structure of Crossrail’s art programme examining the overall vision, the creation of a project delivery team, the curatorial process and policy, funding and sponsorship proposals and the evolution of the programme into a comprehensive project that sought to achieve the following:

– The integration of permanent artwork into the fabric of the network

– The creation of temporary artworks, artist’s residencies and cultural events

– The creation of an artistic record of the project

– A programme that will attract the foremost artists, galleries and curators

– A programme that will help to build the Crossrail brand* Crossrail Architectural Design Guidelines: Vision for the System Pt.2.0, 2009 edition.

-

Read the full document

INTRODUCTION

Crossrail had an obligation to deliver an art programme set by the Sponsors’ requirements for Central Section stations to display sponsored public art.

A programme for the sponsorship of artworks at new stations shall be established by CRL, with display to be considered during the detailed design of these stations in order not to compromise operational, safety or security requirements.

Sponsors’ requirements v.4.1

This obligation represented a great opportunity. It was very clear that a project of such enormous social, economic and historical significance for London and the South East should aspire to deliver a cultural component as part of the overall project programme that would deliver the widest possible benefits for the project, local communities and the surrounding regions.

It was with this broad and ambitious vision that C100 and the Crossrail team embarked on the project for the development of an art programme.

BUILDING THE ARTS PROGRAMME

Prior to commencing the project the team consulted widely to gather opinions and advice from experts in the field, explore the many precedents and case studies available of existing and established art programmes and begin to broker potential partnerships.1

This initial research was used to inform and structure a development strategy for the Crossrail arts programme. The strategy evolved from asking five key questions, which acted as cornerstones from which to begin building:

- Art Programme Model – What do we want to achieve?

- Art Programme Structure – How will we do it?

- Curatorial process & policy – How do we engage artists?

- Art Programme Funding – How will we pay for it?

- The Crossrail Project context – What are the benefits?

There was no funding for art within the original Crossrail project budget. The overriding challenge for this project was to establish an art programme that could become a properly grounded, and fully funded, cultural programme that could be delivered to the project timeline. This had to be achieved during the worst economic crisis since the nineteen-thirties, in a market that was seeing public funding of the arts cut dramatically.

ART PROGRAMME MODEL

What do we want to achieve?

In order to establish a structure for the Crossrail Art Programme the team first had to define a vision for the programme, the key principles that would underpin it and the key objectives that it would set out to achieve.

Vision

The vision, key principles and key objectives for the art programme were predicated upon the ambitions for the Crossrail project as a whole, which were defined in the vision for the new rail network.

Crossrail had a unique opportunity to create a public art programme of global significance. The design and construction of new stations, infrastructure and environments presented major opportunities for the integration of art into the project’s development and realisation. The strategy that was evolved by the project team sought to achieve the following:

- Involving artists in the conceptual development of the new stations

- The integration of permanent artwork into the fabric of the network

- Temporary artworks, artist’s residencies and cultural events

- Creating an artistic record of the project

Crossrail’s vision to support the development of London as a world-class city, and its remit to deliver a world-class railway fit for the twenty first century, could be amplified by an ambitious public art programme whose vision was to enhance the passenger journey experience, improve the quality of the public realm, forge engagement with staff and local communities and encourage ownership of the network that will stand the test of time.

Key principles

The Vision for Crossrail 2 details the rail network’s ambitions in terms of the following components:

- Perception

- 21st Century Design

- Responsiveness

- Integration

- Sustainability and the Environment

- Engineering Design

- Lasting Simplicity and Coherence

- Responsibility

- Value for Money

A programme for art was capable of supporting all of these ambitions but one particular aspect of this vision – integration – offered the team an insight into how they could embed the new network into the cultural identity of its location, and simultaneously open up a range of artistic, financial and organisational opportunities that would support the creation of a public art programme.

Integration

The project will integrate with and be respectful of the fabric of the city, ensuring that the Crossrail facilities and their urban context form one coherent environment. The project will encourage the development of public realm initiatives by other stakeholders to maximise public benefit.

Figure 1 – Integration: Crossrail Architectural Design Guidelines: Vision for the System Pt.2.0

Crossrail has a specific role to play in the development of London as a city, and the South East region of the United Kingdom. It is the specificity of this location that can be celebrated and articulated at the heart of a vision for the art programme.

Founding the art programme upon the idea of ‘Place’ opened up a rich vein for exploration in the development of a structure for the programme that linked it with many of the principles and objectives that Crossrail promoted. It also aligned the project with the common agendas of many of Crossrail’s partner organisations and stakeholders.

Figure 2 – A cross-section of public realm initiatives in 2011

Putting place-making at the centre of the Crossrail art programme gave it a powerful narrative as well as a firm commercial foundation for development. It was a position that others could decide to become involved with and support politically, financially and creatively.

The stakeholders and potential partners considered at an early stage included public bodies, government departments and NGOs, organisations and institutions and private companies.

The establishment of the line-wide of place-making provided a structure for the art programme whilst still allowing for individual proposals to be developed for each location that could be based on the particular nature of that place. This built flexibility into any specific project proposals whilst ensuring that a compelling story could be constructed for the project as a whole.

Place-making, Art and Crossrail

The idea of place-making, using the history of the station’s location as a tool for generating visual difference, can prove as rich for architectural design as it can for art. When considering using history and location as catalysts for architectural design and artistic expression that is seamlessly integrated within the station design, the team were very conscious that poor design could lead rapidly to pastiche.

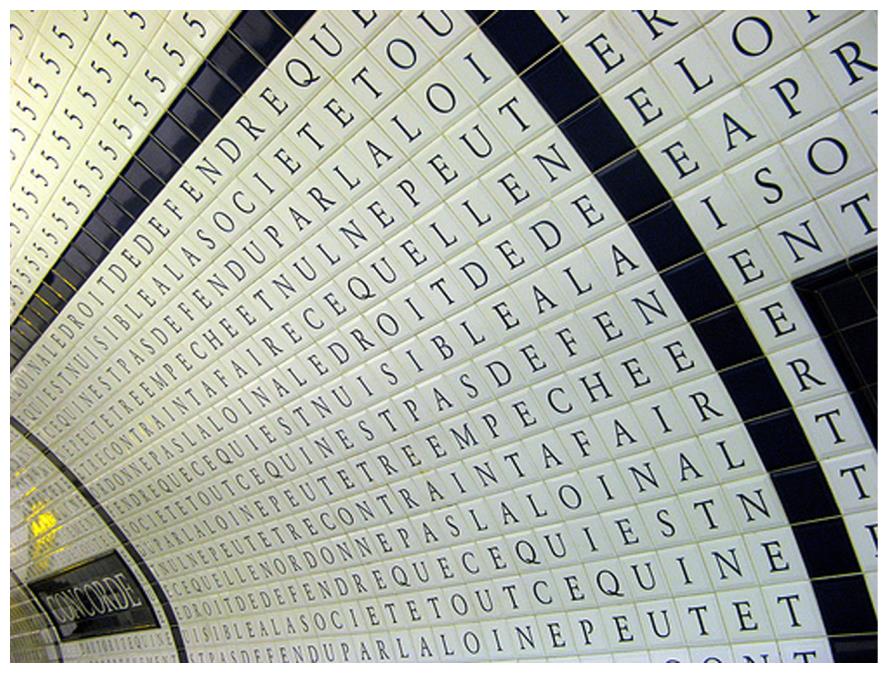

In Paris, on the walls of Concorde station, each tile carries an individual letter, which when read together form the words to the Declaration of the Rights of Man from the French Revolution of 1789. This poetic use of historical association delights and intrigues as its true meaning is slowly discovered.

Figure 3 – Tiled walls at Concorde Station, Paris Metro

This type of artistic intervention was one of many used to guide the early stages of development of the nascent art programme.

Sites for art

The design and construction of the nine new stations along Crossrail’s route, together with five portal structures, were the focus of the development of the art programme. Each of these offered an opportunity for integrating artwork permanently into the fabric of the buildings, the creation of temporary pieces and events that might be associated with the sites’ construction or life in use and the recording of the construction programme by artists.

Of these nine stations the greatest potential for the programme lay within the seven Crossrail stations that form the Central Section area of the line. Each of these seven stations has an historically rich environment from which to draw inspiration for an artistic brief, and within which to forge local partnerships.

ART PROGRAMME STRUCTURE

How will we do it?

An evolving concept

The primary requirement, of the art programme was to broker partnerships between artists and station designers that would enable the creation of public art of an appropriate vision, type and scale for the network.

As the team began discussing the potential structure of the art programme, the concept of a tiered structure for the art programme began to emerge. This structure envisaged a programme that would allow for, and enable, a system whereby a diverse range of artists could be commissioned to provide art for Crossrail across a wide range of opportunities within the project.

The commissioning policy would seek to engage internationally recognised artists, new and emerging talent as well as recent graduates. Commissioning globally recognised artists would give the project a high profile, but would bring with it a higher fee base. Commissioning emerging talent would involve smaller fees, but with good curatorial advice could lead to the project being the host of work that achieved global significance. And commissioning recent graduates, and new talent, would complete the project’s profile as a patron of significance, one that is supportive of the development of the public realm and the global community of artists.

This tiered structure would allow the project team to have far greater ‘volume control’ in how it developed and managed the public art programme, creating a varied portfolio of projects of all scales and types, which would in turn create a sliding scale of sponsorship requirement. This structure had the dual benefit of allowing the project to engage a wide range of artists in the art programme and allow a wide range of businesses, and individuals, to become patrons of the programme via different levels of funding.

Creating a commissioning hierarchy

The concept of a tiered structure for the programme led the team to the idea of developing three types of commission, which would embed the principles of diversity and inclusion into the programme. These three types of commission were as follows:

- Permanent works: works that would be part of the architecture and built fabric of the network

- Temporary works: works that would include the use of site hoardings, events, performances and installations during the project construction

- Project record: works that would record the gestation and construction of the project forming an historical record of the project

These three types of commission would have different roles to play within the project and programme, but combined together they would define Crossrail’s reputation as a patron of the arts and a sophisticated infrastructure client.

In-house, outsourced or a hybrid structure

Once the team had agreed upon the basic idea of a tiered structure for the art programme, for all the benefits it would bring in delivering the project values of inclusion, diversity and engagement, the next challenge was to consider how best to structure the long-term team that could develop and deliver such an ambitious programme.

The team’s research had identified two well established models for structuring a public arts programme, and then a number of variants on these models. The team analysed these precedents in terms of their ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ in order to decide on the best model for the art programme that Crossrail wanted to build.

In-house art programmes

Many modern regions, cities, and developers create programmes for public art that are run by dedicated teams embedded within the organisations. In New York the Design Commission retain an overview of any permanent works of art proposed for city-owned property, and act as caretaker and curator of the city’s public art collection.

Pros

Managing a public art programme within the organisation gives direct control over the whole process involved with creating public art, which has benefits in cost control and the delivery of a consistent and coherent vision.Cons

Recruiting and maintaining a team that has the right abilities and experience takes time, and it brings with it a fixed overhead in terms of staff salaries and associated costs.Outsourced art programmes

Some large organisations treat the creation of a public art programme as they would any other package of work that can be tendered for, and outsourced to an external organisation. The DLR in London has done this and UK Property developers Hammerson followed this route for the Cabot Circus development in Bristol.

Pros

Arts consultancies offer a source of specialist knowledge, experience and project management skills that can help to create and run large-scale public art programmes.Cons

External consultancies can command high consultancy fees, and can reduce the control that a client can exert over a project. Many consultancies have rosters of artists that they regularly use, and this can restrict the ability of the client to commission more widely.Hybrid art programmes

A number of public sector organisations have used a hybrid version of these models, looking to maximise the benefits of each. An example of this is the way that the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) for London 2012 created their art programme.

The ODA formed a small in-house team that developed and led the high-level arts strategy, setting an agenda for all of the works commissioned. This team decided on a project-by-project basis how best to manage and deliver the individual commissions. The delivery can include external arts consultancies, members of the local community or local authority and funding bodies.

Pros

Control of the overall project is maintained within the organisation by a core team of specialists directly answerable to the Project Executive ensuring that a coherent and consistent vision is developed and delivered.Cons

The in-house team need to establish clear management structures for controlling what can be a large number of sub-contracted individual projects.Crossrail art programme team structure

The team developing the art programme decided that a hybrid structure best suited the needs of the Crossrail project. The team reached this conclusion for the following reasons:

- The complexity of the project’s design programme, architecture, engineering and construction meant that only a fully committed, small, focused in-house team would be able to understand, drive, deliver and manage public art as a component of the scheme.

- There were immense financial pressures on the project, and these were likely to increase during the project timeline. The best value for money would be delivered by creating a small specialist in-house team who could draw on the expertise of external specialist consultants.

- Management of individual art projects can be tendered to external consultancies and organisations, so that competitive fees can be secured from the market for shorter fixed term commissions.

The team suggested that Crossrail create a dedicated post for a Head of Arts and Culture. Managing an art programme of this scale and potential is a full time role. It was envisaged that this role could mirror that of Head of Stations, and work in parallel with the whole client design team to ensure an integrated approach to the work.

It was key that leadership should be given to the art programme from the very top of the organisation, and thus it was recommended that a Crossrail board member should be identified to champion the Crossrail art programme. The culmination of this process of structuring the art programme resulted in the following recommendation for an Arts Programme Team 3:

Arts Programme Team (APT)

- A Head of Arts & Culture

- A small in-house project management team

- An external specialist arts advisor

- Representatives from the employer

– CRL Board member

– CRL Design Management (Head of Stations) - Representatives from the project sponsors

– Transport for London

– London Underground Limited - C100 Consultant (representing pan-station design integration)

This structure was proposed as an ideal scenario. However, it was not possible at the time to create a position for a Head of Arts & Culture, and so the C100 team acted as the in-house resource, with specialist knowledge and support provided by external consultants.

The APT were supported by the station designers and were responsible for:

- Selecting artists appropriate to each location and station designs

- Preparing artist’s briefs as appropriate

- Manage designer/artist cooperation

- Monitoring development of and integration with station design

- Identifying opportunities for sponsorship and funding

The APT would be responsible for developing and delivering the art programme over the course of the project. It was also recommended that in addition to the Arts Programme Team the project would benefit from the creation of a carefully selected Board of Trustees, drawing its constituents from the worlds of culture, the arts and finance. Such a board would add tremendous value to the project’s profile and depth of resource.

CURATORIAL PROCESS AND POLICY

Establishing the creative direction

Creation of the Master Brief and securing curatorial expertise

Crossrail needed to build its art programme incrementally, establishing a cumulative process that would over time increase funding and raise the profile of the project.

The first step was taken with the launch of the project to the Crossrail design teams and the foundation of the Crossrail Arts Programme Team. The APT quickly moved to a process of competitive interview to secure expert curatorial experience. Futurecity, an innovative UK based arts consultancy won the contract to help the APT build the programme.

The Crossrail design teams had all presented initial concept proposals for their ideas on integrating art within their buildings, naming artists that they would be interested in working with. Crossrail’s APT gave guidance on the general theme of ‘place’ as an idea that would coordinate the teams’ individual proposals for art so that they could build to create a collection of works under the umbrella of the Crossrail brand.

To move the project forward we needed to create a detailed Master Brief and assemble a roster of artists and galleries that could become involved in the programme. The Master Brief provided a clear and detailed description of the artistic and cultural programme, a schedule of the opportunities that existed on the project and a process for their realisation. It was intended to guide the artists without constraining their creativity, providing an intellectual framework for their proposals.

The Master Brief

The Master Brief identified three principal areas for artistic intervention within Crossrail. 4 These were described in great detail within the Master Brief but can be summarised as follows:

Crossrail Sculpture project

The main material for the construction and finish of the stations, platforms, walls and tunnels is to be glass reinforced concrete. This material is malleable and can be coloured, patterned, extruded, moulded and textured allowing images and text to be set inside the architecture of the stations.River of Light

This proposal was for a digital arts programme, which would see large digital screens installed prominently at each station. There would be designated areas where film and art projections could be shown, and digital wallpaper on the walls for art and advertising with LED lighting that could be programmed to change colour and movement.Urban Gallery

This proposal explored the public art opportunities in the areas in and around the stations and portals. A menu of projects was established as a guide for commissioning artwork for each place, with an emphasis on local character and community engagement. This included sculpture, photography, seating, wayfinding, lighting and events.Developing initial proposals

With the apointment of Futurecity the station design teams teams were briefed to undertake a charrette, a short period of intense creative activity, in which they elaborated initial proposals for art within the station schemes.

The results of this charrete were used to identify artists who could be engaged to partner with the designers, and to explore holding a competition organised with major art schools. The student prize would be a chance to work with the integrated teams, working alongside the established lead artists.

Project selection

Proposals tabled by the teams were assessed by the APT. The team decided which proposals were suitable for development and had the potential to attract corporate or individual sponsorship.

Sponsorship prospectuses and presentations could be designed and made for each station, and for the project as a whole, to provide material with which to begin to atttact seed funding from potential programme sponsors.

Securing sponsorship

The final step in establishing the project on a firm foundation came at the end of 2010 with a presentation to the City of London, organised in partnership with the London First group. This presentation launched the programme and sought to secure initial sponsorship pledges for all of the proposals that the teams had elaborated. This initial funding would allow for the development of the proposals, prior to a second round of funding for implementation.

ART PROGRAMME FUNDING

How will we pay for it?

In 2010 central government funding for arts and cultural activity in the UK was cut by £60m. In it’s place the new government promised to create a landscape where personal and corporate philanthropy would fill the void. In 2009 £655m was made available to arts and cultural organisations in the UK through the funding efforts of personal and corporate philanthropy. However, the financial crisis was creating an intensely competitive landscape in which the challenge of securing a slice of that investment would only be achieved by projects that could excite the interest of sponsors by the level of the project’s ambition.

The principle of a tiered structure that had been used to underpin the overall vision for the arts programme was applied to the ideas for creating a funding structure. The team decided that the best prospect for securing funding of the programme was to target a variety of potential sources. These were classed as primary, secondary and tertiary sources of project funding.

Primary funding

A firm baseline funding needed to be established to make the project viable. Primary funding would act as a catalyst to attract other sources of funding from the public and private sectors; it would give the project credibility.

Secondary funding

Secondary funding can come from a variety of sources.

Grants and awards

Grants and awards are available for public art, such as those from the Gulbenkian and Clore Foundations, or those offered by Arts Council England. These sources of funding often like to use their comparatively small grants to support and engage with a larger project.Statutory funding

Local authorities use Section 106 planning agreements as a source of funding for public art. Many of the counties and London Boroughs that Crossrail passes through have established arts policies and Art Advisory Panels. Partnership with local authorities was identified as a potentially useful tool in developing the art programme for Crossrail.Philanthropy

Private benefactors or institutions could be encouraged to become involved in the Crossrail Art Programme. There is a long tradition of philanthropy in the United Kingdom but it faced extraordinary demands as the financial crisis deepened. The idea of creating the Board of Trustees for the art programme was designed to engage directly with this audience of philanthropists.Sponsorship

Alongside philanthropy, or gifting contributions to the project, there was scope to consider using sponsorship as a funding mechanism for the programme. Controlled sponsorship could be a useful mechanism to leverage funds for investment in the art programme.Revenue offset

The Art Programme Team were very clear that the programme needed to be considered as a living entity, not as a project that stopped when Crossrail’s construction phase was complete. Funding was an on-going issue.A way to leverage continued investment in the art programme would be to consider offsetting revenues from income such as advertising. Partnering with a media company to manage the advertising network was identified as a way to generate income from advertising to fund artistic content.

Tertiary funding

Crossrail’s Central Section stations run through the densely populated heart of London and will become prime generators for London’s continued growth. The stations have the potential to directly engage with local boroughs, businesses and stakeholders and support their plans for the development of their area. And in turn these stakeholders can support Crossrail and its art programme.

Cultural Mapping

Arts organisations and local boroughs have become increasingly inventive to realise the funding required for projects that they want to undertake.Creating ‘Cultural Maps’ of the areas surrounding the new Central Section stations helped to identify key attractions – museums and galleries, colleges and universities, theatres and clubs, restaurants and bars and tourist attractions – and ‘mapped’ the potential beneficiaries of the new stations. These beneficiaries are potential partners for the development of art projects.

Institutions and galleries provided a specific target for partnership in the development of the Crossrail arts programme Many institutions, such as the Barbican and the Whitechapel Gallery, have programmes whereby they look to take their artistic programmes beyond the walls of their buildings and into the public realm. Their initiatives embrace traditional conceptions of public art, such as sculpture, but include the full gamut of artistic expression including theatre, event, music, digital and experiential art.

Funding summary

The process summarised above gave the Crossrail Arts Programme Team a clear direction in which to develop the Crossrail art programme. It took the form of simple, incremental steps. Each step facilitated the next step. Each step built the project’s profile, and engaged the attention of potential sponsors.

Seed funding from the project set the ball rolling. It got the programme to the point where proposals for art could seek funding. With that funding in place it will be possible to develop and realise the proposals.

The initial development phase of the programme secured early support from Arts & Business, the Arts Council, The Photographer’s Gallery, the GLA, a number of independent art galleries and a host of other organisations.

THE CROSSRAIL PROJECT CONTEXT

What are the benefits?

The art programme delivers significant benefits to Crossrail. These include:

- Helping support London’s status as a world-class city

- Creating a memorable cultural identity integral to the rail network

- Marketing Crossrail as a cultural network and destination

- Connecting Crossrail to its staff, passengers and communities

- Supporting the project’s aims for sustainability and integration

- Improving the public realm of the city of London

- Capitalising on the growth of cultural tourism

- Partnerships with cultural organisations and business sponsors

- Forming a unique part of the public record of building Crossrail

Public art programmes make a significant contribution to the cultural identity, brand perception and marketing of a city, region or service. They add tangible value. Day-to-day they enhance the passenger journey experience, improve the public realm and encourage network ownership. This ownership has been shown to lead to a decrease in vandalism, and a ‘policing’ of the system by its staff and users.

Crossrail has had a long gestation period and is being designed, and built, in a period of immense economic turmoil. This places the project under great financial and political scrutiny. The benefits of the project to London, the South East and the nation as a whole are well recognised, but the project needs to embrace and promote every element within its scope that can engage the imagination of the body politic and the public at large.

CONCLUSION

There is a powerful and engaging story to be built, and communicated, about the Crossrail public art programme. There is a chance to create a network that has a unique quality within the world of modern infrastructure development. The challenge that remains for Crossrail is to develop and deliver the full potential of the project that the Crossrail Arts Programme team began in 2009.

-

Authors

Robert Wood BSc(Hons)(UCL) DipArch(Cantab) RIBA L’Ordre des Architectes Francais D&AD - Crossrail Ltd

Interface Manager C100 Architectural Components, Crossrail

-

Acknowledgements

Eric Parry RA

Sarah Weir, Head of Arts & Cultural Strategy, Olympic Delivery Authority

Amanda Smethurst, Director, Arts Council England

Louise Trodden, Head of Art, Open House

Piers Masterson, Arts Development Officer. LB Camden

Sarah Collicott, Director, InSite Arts

Sam Wilkinson, Director, InSite Arts

Vivien Lovell, CEO, Modus Operandi Art Consultants

Tamsin Dillon, Head of Art, London Underground

Munira Mirza, Director, Policy for Arts, Culture, Creative Industries

Justine Simons, Head of Cultural Policy, Mayor's Office