Implementing Project Community Relations

Document

type: Technical Paper

Author:

Gareth Epps AMCIArb

Publication

Date: 02/12/2021

-

Abstract

Crossrail was one of the first projects to feature specific community relations requirements from the outset. Some of these were Parliamentary requirements and therefore binding towards those carrying out construction work; others a development of best practice from elsewhere. Throughout the consultation and authorisation phases of the project, neighbours raised issues and expressed concerns about aspects of the work and its impacts.

This paper sets out the overall approach the project took to codifying and implementing these requirements, and some of the challenges encountered in so doing. It will be of interest to those involved in major civil engineering projects, particularly those affecting major urban areas

-

Read the full document

Introduction

After Royal Assent was achieved for the Act of Parliament granting powers for Crossrail, the commitments made during the Parliamentary process were required to be turned into commercial contractual requirements to ensure that they applied to contractors, and thus to subcontractors and the supply chain.

Crossrail’s requirements for community relations came in different forms. In drafting the documents, commitments given in Parliament and by project sponsors and leadership needed to be translated into deliverable contractual requirements. Many of these requirements were implemented directly by the Tier 1 contractors engaged on the project.

Establishing Community Relations requirements

Crossrail’s requirements for community relations came in different forms. Some were reported to Parliament as Undertakings and Assurances given by the Secretary of State; formally recorded in a Register and monitored. Other commitments were contained in the Environmental Minimum Requirements for the project, developed to provide a consistent approach among consent granting authorities – in this case principally local government. Some commitments were made in response to specific issues raised during the Hybrid Bill process (such as the requirements of the Parliamentary Select Committee for a ‘monitoring body’ with communities in Spitalfields/Whitechapel, subsequently in the Paddington and Barbican areas); others (such as the requirement for a Complaints Commissioner, an office of last resort to mediate in unresolved complaints independent of the project) stemmed from best practice on other projects such as the Channel Tunnel Rail Link. The level of detail of the commitments varied considerably.

While most of these commitments relating to community relations were recorded in the Community Relations Strategy Framework (‘the Framework’), an exercise was undertaken to ensure consistency with any commitments made elsewhere. The Framework was developed from 2005-7 in an iterative process with partners[1]; at the request of project local authorities the Construction Code was amended to require commitments in the Framework to be written down as contractual requirements, to provide assurance that the commitments contained therein would have the same statutory weight as Environmental Minimum Requirements.

The Framework was envisaged as a company document governing policies and procedures, though it was shared with the Crossrail Planning Forum (the umbrella body for qualifying route local authorities, set up to facilitate the expeditious provision of the planning and other relevant consent granting elements of the Crossrail programme). It sat alongside a range of other project procedures covering such matters as complaints handling and the operation of the Public Helpdesk, designed to ensure the effective operation of the client body. A detailed Equality Impact Assessment, published in 2006, provided additional demographic information and made non-binding recommendations.

While there was no formal process to learn the lessons from previous similar projects such as the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL), guidance was taken from a review and Lessons Learned document produced by the outgoing CTRL Complaints Commissioner[2], Professor Tony Kennerley.

Requirements for Crossrail Contractors

Following Royal Assent, the commitments were required to be formulated into unambiguous contractual requirements. The commitments were initially tabulated, then developed into deliverable commitments by the client or contractor (or both). Project requirements were incorporated into company procedures; any actions falling upon principal contractors were developed into the Works Information documentation produced to encapsulate all contractual requirements. This was developed by way of an iterative process to ensure consistency with other contractual requirements and, as far as possible, to ensure compliance. Key areas of activity covered by these policies included:

- Information provision requirements, for the provision of information sheets and updates (Figure 1a);

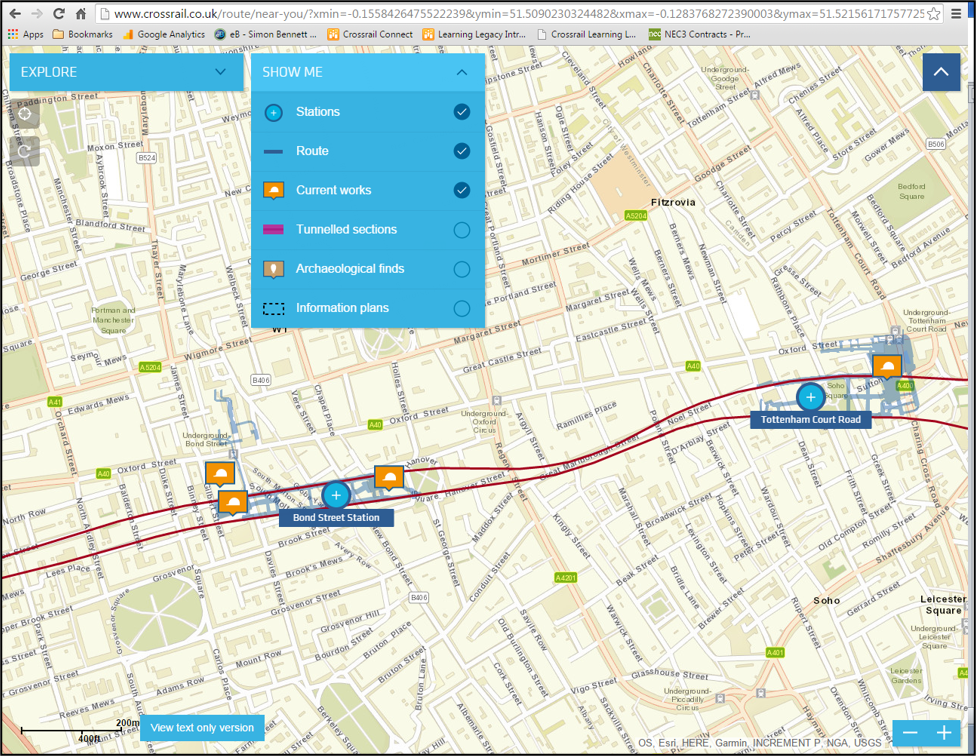

- Information on the progress of tunnel boring machines (to meet a Parliamentary requirement that such information should be published, Figure 1b);

- Complaints handling responses;

- Mapping of the local community and key interfaces through a liaison plan;

- Participation in structured community liaison activity (Figure 2).

Although it was not contained in the commitments given to Parliament, Crossrail also set out a requirement for principal contractors to commit to a Community Investment Programme[3].

Figure 1a. Information Sheet

Figure 1b. Near You website

Figure 2. Contractor Community Event

Community Relations management

In line with the transitioning of the client body into a delivery body, the structure of local stakeholder engagement activity within Crossrail Ltd changed to focus on supporting delivery teams with the community relations requirements. Dedicated community relations personnel were assigned to work with principal contractors, briefing client project managers and contractual representatives; contacts were assigned to principal contractors and local authorities, partly to assist in relationship-building.

To meet one of the commitments given to Parliament, a routewide set of community liaison panels was set up, covering the area surrounding each tunnelled station (separate arrangements were agreed for Canary Wharf). These were to be independently chaired, normally by a member or officer of the lead local authority, to build confidence and trust. They were comprised of stakeholder groups, such as residents’, tenants and business associations; all local ward councillors were invited. Principal contractors were given responsibility for presenting and responding to questions relevant to them, and senior project delivery personnel were present to cover broader project-related issues.

Figure 3. Community Liaison Panel

The project also addressed ‘responsible procurement’ requirements[4] and steps were taken to ensure these requirements were explained to local communities as far as possible; particularly relevant to community relations activity was schools engagement.

In parallel to the early works undertaken by principal contractors, a number of other advance works were required. These included the strengthening and detailed mapping of utility assets, and programmes of statutory mitigation such as installing noise insulation to a significant number of properties along the route. These works were managed under separate arrangements to main works contracts, and required community relations activity to ensure those affected were informed and any relevant mitigations put in place. Actions not set out in contractual requirements were delivered by the project’s community relations staff, such as the provision where relevant of alternative communications mechanisms, such as translations.

As Crossrail emerged from the Parliamentary process, some of the most sensitive aspects of the project’s design were still being addressed in technical terms. In particular, the most sensitive proposal, generating significant localised campaign activity and petitioning against the Bill throughout the Parliamentary stages, was the impact of the tunnelling strategy that proposed the launch of tunnel boring machines from a shaft facility at Hanbury Street, just off Brick Lane in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The proposal impacted the community in Spitalfields, and would have required significant heavy goods vehicle movements along minor roads, affecting a number of schools. The Parliamentary Committee assessing the Bill required extensive community liaison in the area, which proved challenging given the context of the tunnelling proposal. During the Bill process, there were legal constraints on what the project could do to engage communities along the route. In late 2007, the tunnelling strategy was altered, with the scale of proposed works at Hanbury Street being reduced to the formation of a ventilation and intervention shaft[5]. There remained significant community concern at the impact of the works at this location, and decisions were taken to remove the shaft completely, subject to reaching agreement with the London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority (LFEPA). This was achieved in 2009. Nonetheless, as this sensitive and confidential work was taking place, meaningful liaison was still required to provide reassurance to communities in this area.

To transition from the Parliamentary process into a delivery body, many of the community relations personnel retained oversight of their particular area. As construction activity developed, that team was strengthened, being formed on a basis of London borough boundaries to simplify accountability and a series of regular liaison meetings with officers of each local authority was set up to each authority’s particular requirements led by the programme community relations team and involving the relevant Crossrail area directors and project managers. By 2013, there were ten members of Crossrail Limited’s community relations team with area responsibility, but an additional 20 community relations representatives (CRRs) employed by principal contractors to discharge their statutory responsibilities[6]. These staff helped to handle enquiries and complaints, led community engagement and assisted in bringing issues to the attention of relevant project specialists. Of particular importance was the need for those representatives to be directly involved in programming decisions where there was an impact on the project’s neighbours, so the impacts could be identified and mitigated in design, or given proper consideration. The examples where this did not take place were rare, but tended to generate adverse feedback.

Reporting requirements as set out in the Community Relations Strategy Framework generated regular periodic reporting that described community relations activity in considerable detail; while this undoubtedly aided transparency and benefited relations with local authority stakeholders in particular, the detail required may have been disproportionately onerous at certain times in the project.

As the project evolved, a strategic approach was developed that prioritised the management of reputational risk to the project from such factors as the cumulative impact of multiple contractors or other works in a borough or area. This became important as the project began to plan for particular milestones, such as the closure of roads which were key bus corridors (such as Eastbourne Terrace at Paddington, where reassurance was needed and given that the closure would be for no more than the minimum period of two years that was required for safety reasons[7]). This required forward thinking and advance planning, and proved beneficial in engagement with principal contractors. In parallel, it ensured that all personnel knew particular risks could be raised, discussed and appropriate action taken before particular impacts arose; it provided an additional mechanism for issues to be brought to the attention of relevant project leadership.

Lessons learned

It was noticeable in forming project requirements on community relations that there was no formal process of knowledge transfer from previous projects[8]. While input was given by the project’s Programme Development Partner and from the experience of individual staff members on previous projects, there was no record evaluating the success or effectiveness of measures and techniques deployed[9]. Contractor feedback was sought during the project and one example of comments received is provided in the Appendix.

The early engagement of contractors’ community relations representatives with the community proved beneficial wherever this was possible. In a small number of locations, the need to finalise aspects of project design or gain approvals led to delays in engagement; from a contractor’s perspective, this meant that the project ‘started on the back foot’. Another aspect of early works in an urban environment which significantly enhanced community relations where completed in time, and generated problems where it was not, was the provision of noise insulation. Appropriate levels of resourcing and prompt decision-making in advance where relevant construction impacts were identified made a significant contribution to preventing significant disruption[10].

While feedback was hard to measure in quantitative terms, the reception for the community liaison panels was positive[11]. This was partly because local participants were able to raise issues and receive responses; detailed minutes were produced, and the independence of the Chair provided points for escalation of any issue where it was felt that responses from the project had not resolved it. In the early stages of construction in particular, it enabled the project to answer questions from communities that could only be addressed at contractor level. Over time and particularly past the peak of heavy civil engineering works, attendance at panels decreased, and the frequency of the meetings started to reduce, by agreement with all involved[12]. From 2012, Crossrail partnered with IPSOS MORI to better understand stakeholder opinions of Crossrail, with particular focus on residents near to works areas and Helpdesk correspondents. This provided helpful information that, to the extent it was possible, benchmarked the project’s reputation.

However, for one route section experiencing works but no station, regular liaison had to be requested. At North Woolwich, part of a former surface railway line through the peninsula was used for the route and northern portal of the Thames Tunnel. Feedback from the community had been limited through the consultation and Hybrid Bill processes, and few formal complaints were made; there were notably fewer residents’ or stakeholder groups in the area. However, some local residents started to express frustration at aspects of the works, and formed a group to lobby their elected representatives. This resulted in some open meetings being held; the principal disadvantage of those being that it was challenging to record and respond to complaints and issues raised in a transparent way[13]. Over time, the project had to evolve alternative methods of responding to individual residents in the area, and held meetings with council members and officers, but this engagement lacked the consistency and timeliness of community engagement elsewhere.

Across major projects, there is a need to ensure commitments made at an early project stage (prior to Royal Assent) can be realistically applied and do not set undue expectations. Language needs to sufficiently specific to be resilient to commercial challenge and also reflect the commercial reality. For example, the commitment to provide a Small Claims Scheme needed to be consistent with ways in which insurance deductions were made from contractors. Similarly, requirements on contractors to provide works information well in advance of potentially intrusive construction activity wherever practicable proved challenging against the expectations of surrounding communities and was at times seen as unachievable by contractors, so was hard to enforce. Inclusion in project decision-making processes, including change management and control processes, formed an important part of broader risk management.

The degree of early engagement with contractors at an appropriate level was variable. At an operational level, close relationships were formed between Crossrail’s community relations personnel and their equivalents at contractor level. However, at projectwide level the benefits of sharing best practice among community relations specialists were achieved later; it would have proved beneficial for briefings for early works personnel to have taken place on a more regular basis. Similarly, it would have been beneficial to develop a structured mechanism for community relations objectives to be discussed with project directors at an early stage of the project, potentially following kick-off meetings.

The operation of the contractor Performance Assurance Framework[14] proved particularly beneficial. It provided a platform for a series of discussions with contractors to focus on key issues faced by each contractor; a more strategic basis for evaluating progress and identifying where briefing gaps or local anomalies existed; but also supported contractor teams by recognising industry frontier performance being achieved across the project, building self-confidence.

The noise insulation programme was managed separately to the early works contracts[15]. At the time, it was the biggest programme of statutory noise insulation undertaken on a major project and so considerable resource in contacting and arranging this necessary form of mitigation was required. This work was ultimately taken on by Crossrail’s community relations team; however, in terms of supplier engagement and the ability to meet public expectations, it would have been beneficial for it to form part of a contract package[16]. Similarly, the management of utilities works, necessitating considerable streetworks and alternative arrangements for businesses, provided challenges that would have been addressed as part of a contract package. In particular, significant resource implications arose that could not be foreseen.[17]

Crossrail through its community investment programme was an early adopter of what is now known as social value. Its contractual requirements predated any social value legislation; contractor goodwill was required to deliver meaningful and targeted investment, and dialogue was important to identify optimum projects and maximise the delivery of lasting legacy. The review of the project’s approach in 2013/14, resulting in an early form of quantifying support that included a broad range of activity such as volunteering, led to significantly greater positive impact being made. The advantage of the approach taken by the project was that investment was linked to local project impact wherever possible, and it enabled alternative forms of discussions with the industry that at its best led to an enhanced sense of the project ‘giving back’ in a manner that used public money responsibly[18].

Recommendations for Future Projects

- A formal body for knowledge transfer and lessons learned in community engagement

- Specific measuring and evaluation of the community relations approaches of principal contractors from the start, including utilities and other early works

- A thorough appraisal of the resources required to deliver appropriate noise mitigation is a critical factor in the success of early works on major projects in urban areas

- A clearer and phased plan for engagement following the outcomes of a Hybrid Bill process into delivery and advance works is essential to span the project phase where the responses to community concerns need to be directly understood and addressed

- Reporting mechanisms can aid transparency and build trust among stakeholders such as local authorities; however, it is important that reporting requirement are kept proportionate and not be seen as overly burdensome.

Conclusion

Crossrail was a pioneering project in delivering an enhanced range of measures to reassure and mitigate the impacts of the project on communities. While benchmarking the effectiveness of these measures proved difficult, it was a vital step towards giving contractors the confidence to manage their relationship with communities.

Before that, however, the transition from a legislative promoter to a project delivery authority provided a number of challenges. Challenges were experienced in providing early reassurance to the public; these were largely stabilised by the introduction of community liaison procedures across the central section of the route. The process of turning Parliamentary commitments into contractual requirements for main civils contracts was trouble-free; however, to ensure consistency it is important that any works with public impact be addressed by these processes.

Footnotes

[1] Subsequently these and other commitments were turned into an Interface Document with Network Rail for use on the surface sections on the existing rail network.

[2] As with Crossrail, an independent position appointed via the project High Level Forum, attended by local government leaders along the route as directed by project sponsors.

[3] As it was not a commitment, specific principles for Community Investment projects were only developed in 2012. These were then assessed as part of the Supplier Performance Assurance Framework process. This programme was reviewed and developed in parallel to that process.

[4] See https://learninglegacy.crossrail.co.uk/learning-legacy-themes/procurement/responsible-procurement/

[5] See Information Paper G3 for a formal summary of this proposal.

[6] As reported in the Community Relations Annual Report, 2012-13

[7] A timescale which was achieved, with the TfL Commissioner driving a Routemaster bus down the reopened route on the second anniversary of the closure to celebrate the reopening.

[8] See also the recommendation of Ian Bynoe in an investigation into property acquisition and liaison issues on HS2

[9] However, the Complaints Commissioner for the Channel Tunnel Rail Link project produced a report outlining his recommendations and lessons learned. This was a valuable document.

[10] Additionally, consideration of heritage impacts on noise insulation installation is an essential advance consideration.

[11] The project set out focus groups as part of a review of liaison panel activity in 2014. This and broader IPSOS/MORI survey data demonstrated improved favourability over time, and that stakeholders felt their concerns were addressed and relevant and helpful information provided in the meetings. Ensuring consistent quality of tone was important, as was regular outreach to ensure the panels were inclusive.

[12] The project reviewed the operation of liaison panels in 2014-15 and produced a range of recommendations, and considered the point at which they ceased to provide particular value for those involved.

[13] A point made by the Crossrail Complaints Commissioner as part of his reporting processes.

[14] Referred to in other Learning Legacy publications.

[15] On HS2, noise insulation works has formed part of early works packages. While there have proved challenges in delivering that programme, not least in terms of scale, there have been benefits in adopting this approach.

[16] [Delete if not appropriate] There were also issues of supplier capacity experienced; at times these had impacts on works in specific locations.

[17] However, the nature of a major civil engineering project in an urban environment is that challenges with buried services emerge and have to be mitigated. This occurred in two locations on the Crossrail route, both requiring significant community relations activity and coordination. Some contingency would always be required.

[18] The Community Investment programme was explicitly excluded from contractual cost considerations. Changes as a result of the Social Value Act 2013 and public procurement regulations in 2020 now mean that public procurement for infrastructure projects include evaluation of social value, and that this aspect of works must by law be considered

Appendix

‘What went well’ feedback given by a Crossrail contractor in 2015

What worked well?

- Senior management understanding of the role. Being given the freedom to attend whatever meetings necessary and without invitation. This raised the profile of the role to the whole team.

- Community Relations Manager a member of the project senior leadership team and able to influence construction team.

- Reviewing work package plan before an activity goes to construction means that no activity should slip the net and will always be communicated if necessary.

- Planned engagement. Identify all stakeholders and schedule meetings with all.

- Membership of a local regeneration partnership – the service provided in opening doors with community partners has been invaluable. Further to this, the membership meant that [groups such as these and also BIDs] through association had to treat the project as a member rather than fight it.

- Building personal relationships with the business stakeholders. Understanding what their pressures are and working with them to find mutual ground. Even the most challenging stakeholder appreciated the regular face-to-face communication provided on his own terms.

- Following on from the previous point, being flexible about how you deliver messages and make sure it is always on the stakeholder’s terms.

- Been seen to go out of your way to get messages to the stakeholders and to get back to their queries quickly.

- Always deliver what you promise and provide regular updates on its progress.

- The noise trigger action plans although very time consuming built up a great deal of trust with key stakeholders. Working closely with the environmental manager, engineers and foremen to make sure that the investigation reports are quality and prove we are taking the noise levels seriously.

- Sitting next to the CRL counterpart and approaching all items as a team. This builds up trust and also is more efficient as it removes levels of communication.

- Regular informal progress, risk, communication discussions with CRL.

- Sitting in same area as Environment Manager and CRL Environmental Adviser – this allows informal discussion to take place easily and that everyone is kept up to date with any issues.

- Regular meetings with the project planning manager and Agents to identify potentially sensitive operations or PR opportunities.

-

Authors