Third Party Technical Interface Management

Document

type: Technical Paper

Author:

Geoff Rankin CEng MICE MAPM

Publication

Date: 14/02/2023

-

Abstract

The Elizabeth line traverses some of London’s most dense and evolving metropolitan areas. Safeguarding of the route has played an important part since the identification of a tunnelled route back in the early 1990s, following promoters’ recognition of the need to preserve and protect necessary building space and to manage interfaces with adjacent properties and developments.

This paper reflects experience and lessons learned while managing the potential impact of many third party developments during construction of the Central Section of the railway between Royal Oak Portal in the west, Pudding Mill Lane Portal on the northeast branch towards Shenfield, and Plumstead Portal on the southeast branch towards Abbey Wood.

-

Read the full document

1 Introduction

The Elizabeth line traverses some of London’s most dense and evolving metropolitan areas. Safeguarding of the route has played an important part since the identification of a tunnelled route back in the early 1990s, following promoters’ recognition of the need to preserve and protect necessary building space and to manage interfaces with adjacent properties and developments. This paper reflects some of the author’s experience and lessons learned while managing the potential impact of many 3rd party developments during construction of the Central Section of the railway between Royal Oak Portal in the west, Pudding Mill Lane Portal on the northeast branch towards Shenfield, and Plumstead Portal on the southeast branch towards Abbey Wood.

2 Crossrail Safeguarding – Crossrail Asset protection

In 1990 the Secretary of State exercised powers to issue a statutory instrument called a Safeguarding Direction for the Crossrail scheme to protect the route corridor and to mitigate and manage the risk of 3rd party development impact on the new railway. The Safeguarding Directions were updated thereafter as necessary to accommodate amendments to proposals.

During scheme development a team was established to manage Safeguarding, and the responsibility remained with London Underground between the 1990s and 2000s. When Cross London Rail Links (later Crossrail Ltd.) was set up in 2001, the Safeguarding team transferred into it along with the other TfL and London Underground planning and engineering teams responsible for Crossrail.

Crossrail Ltd. (CRL) picked up the mantle of reviewing and commenting on outside party development proposals within Safeguarding Limits referred to it by local planning authorities, and guiding interfacing developers towards solutions addressing Safeguarding concerns and requirements. This positive approach sought also to help realise the wider economic benefit of the new public transport system, thereby helping to deliver Crossrail’s business case.

In addition to route plans published under the Crossrail Bill Documents, a set of bespoke Crossrail guidelines defining constraints were developed and in 2009 a version was published which included methods for calculating ground settlement impact from tunnelling, and transmitted groundborne noise & vibration impact from the future operational railway. Several revisions and addendums followed keeping in step with construction progress, and also embracing TfL’s standard S1023 (Infrastructure Protection) and guidance document G055 (Deep Tube Tunnels and Shafts). The final construction phase edition – Crossrail Information for Developers March 2019 – is appended as a supporting document to this paper. Infrastructure Protection for the Elizabeth line was handed over to the TfL infrastructure protection team, therefore this paper doesn’t cover the post-Handover process for the Elizabeth line. (For further information and guidance please contact the TfL London Underground and Rail Infrastructure Protection team.)

3 Crossrail Safeguarding team – during construction

The safeguarding team key roles changed little over time. The key personnel were:

Crossrail Safeguarding Manager:

The Safeguarding Manager reported to the Crossrail Property Director and was responsible for the management of the team and for maintaining the Safeguarding limit plans, and for providing guidance and strategic decision making in the interests of protecting the Crossrail route throughout the project’s duration, and for overseeing Safeguarding communications with the Secretary of State.

Crossrail Safeguarding Planning Officer:

The Planning Officer reported to the Crossrail Safeguarding Manager and was responsible primarily for drafting and communication formal responses to Planning submittals received, to the local and other statutory planning authorities. The Safeguarding Planning Officer also had a comprehensive knowledge of the Safeguarded extents and vested land and subsoil extents. Crossrail were fortunate also to have continuity of its Planning Officer for the duration of construction.

Crossrail 3rd Party Developments Manager (Later Infrastructure Protection Manager)

The 3rd Party Development Manager was responsible to the Chief Engineer, for reviewing and accepting or objecting to 3rd party developers’ technical proposals, ensuring these adequately mitigated impacts on Crossrail. They also worked closely with the Crossrail Safeguarding Planning officer, 3rd party developers and internal stakeholders, and consulted and coordinated extensively with CRL supporting disciplines (Legal, Planning and Environment, Community Liaison Officers, Surveying, Insurance, Land & Property, Crossrail Framework Design Consultants and Crossrail construction project teams), towards achieving expedient coordination and management of outside party project interfaces; also orchestrating implementation of infrastructure protection measures where necessary (such as in-tunnel monitoring). The process of technical coordination and management adopted is covered under the CRL Safeguarding Review and Acceptance Procedure which is appended to this paper.

The 3rd Party Development Manager also prepared and distributed regular bulletins to senior management, promoting visibility and awareness of the many 3rd party development interfaces affecting the project delivery. Comprehensive records were also maintained in a database for all significant interfacing projects. This proved a valuable reference on numerous occasions.

4 Crossrail Safeguarding – Risk Management

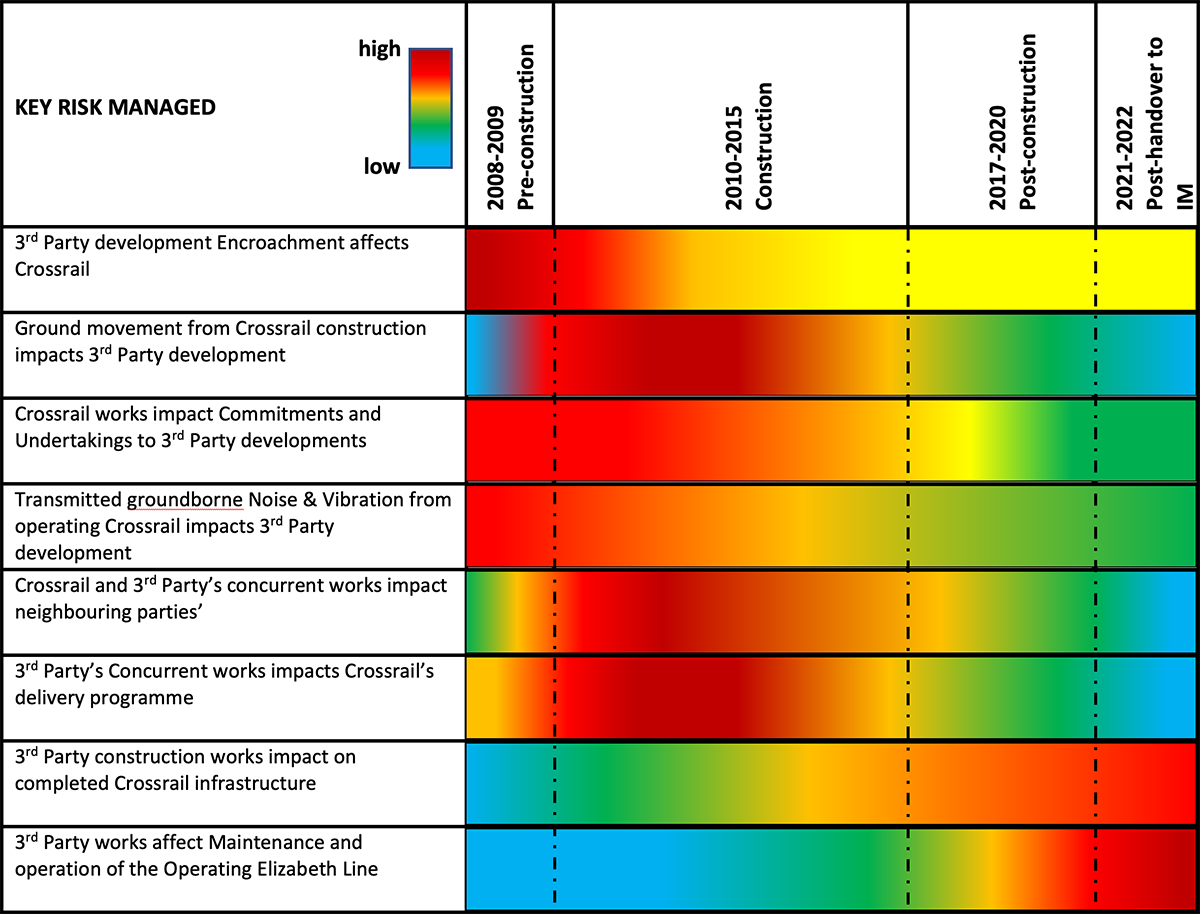

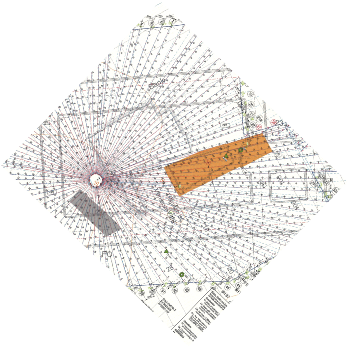

Figure 1 below presents a heatmap of the key risks in time, which the Safeguarding team were responsible for managing, and which are further discussed below for the benefit of sharing experience and lessons learned.

Figure 1: Key 3rd Party risks over time

4.1 Risk: 3rd Party development encroachment affects Crossrail

4.1.1 Space-proofing

The Crossrail Act 2008 afforded CRL powers to acquire land and subsoil in which to legally build the railway. In the days prior to construction, safeguarding offices, solicitors, engineers and planners worked hard to vest the land comprehensively, to secure the routeway as well as adequate subsoil land for temporary works and reservation of haulage routes. Doing this thoroughly was important to also to mitigate the risk of potential 3rd party claims, delays and disputes.

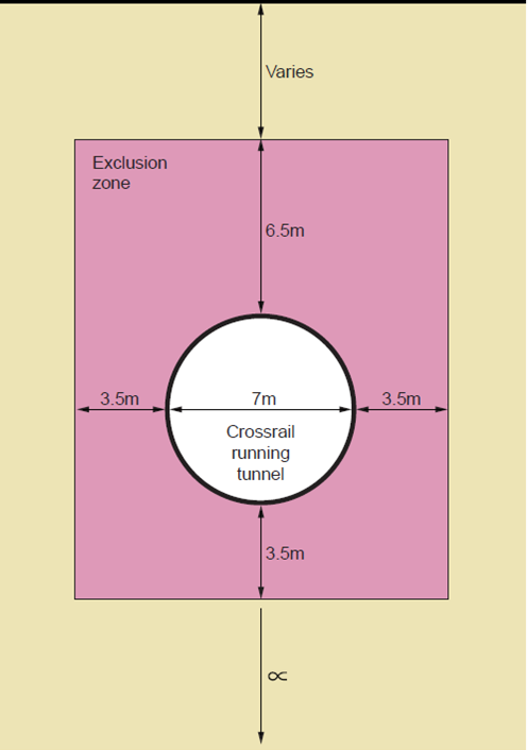

Generally the subsoil prism procured in which to drive tunnels comprised 3.5m lateral, 6.5m vertical above, and 3.5m vertical below tunnel extrados as designed at the time of vesting.

Figure 2 – Extent of subsoil prism vested in Crossrail

Vesting also provided rights to Crossrail to exclude from the subsoil prism outside parties’ works (such as piles, temporary excavations, drill bores etc.) that might otherwise impact railway infrastructure. During design development, tunnel alignments were refined and optimised, so the as-built tunnel is not always symmetrically placed within the vested subsoil, thus requiring further spatial clearance checks always to be undertaken during the Crossrail Safeguarding team’s technical review of 3rd Party Developers’ proposals (allowing also for their temporary works).

The Crossrail Safeguarding direction required Local Planning Authorities to consult Crossrail for all planning applications received under the Town & Country Planning Act, within Crossrail Safeguarding Limits (extending up to 30m either side of the railway corridor). This provided very good visibility and early warning of development impact although there were still a few instances where development applications were notified late or possibly not at all. In such instances fortunately the 3rd party developers took the initiative with some guidance from the Safeguarding team, to contact Crossrail and work within the spirit of the Safeguarding direction, and these development interfaces progressed smoothly. The fact that the numbers were very small is a likely testament to good and consistent communication protocols and good understanding forged between Crossrail’s Planning Officer and the local planning authorities.

4.1.2 Ground movement impact from 3rd party development

Managing encroachment also benefitted the project through reduction of ground movement impact on buried Crossrail assets. The Information for Developers guidance addresses the subject extensively.

A key lesson for future projects is that 3rd party interfacing engineers should consult with their engineering design colleagues at an early stage to interrogate and understand the allowable tolerances of movement-sensitive railway systems, such as platform edge screen doors, lifts and escalators, overhead line equipment, and also significantly rail track forms (especially floating track which may be ultra-sensitive to out-of-alignment displacements). Likewise allowable differential movement tolerances between tunnel, station and shaft connecting structures should be established, also taking into consideration allowances for the mass of any over site developments. It is always worth asking if sufficient displacement tolerances have been allowed for ground movement imposed by 3rd party developments impacting during the 120-year life span.

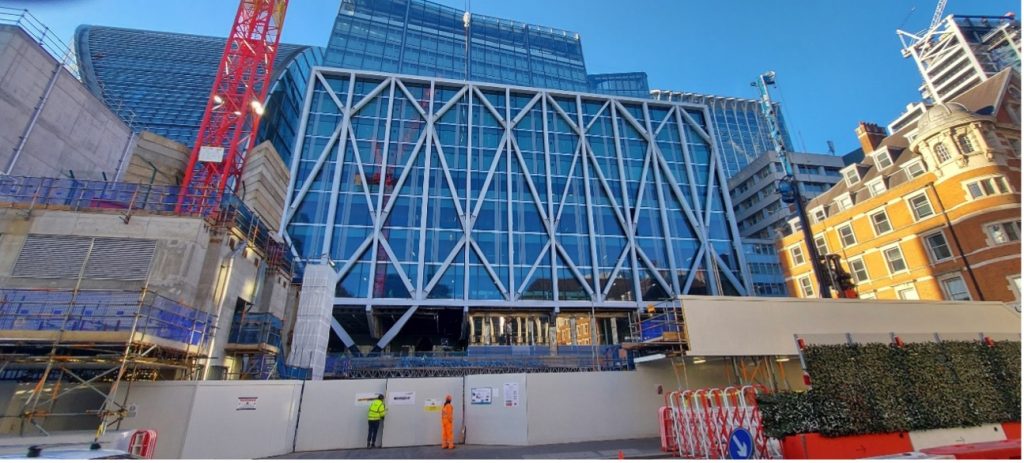

Figure 3 shows the development at 21 Moorfields which oversails the Crossrail entrance above Moorgate station. The entire building also bridges over the Moorgate sidings, relying on large diameter (circa 2.5m) piles bored to within approximately 3m of the Crossrail running tunnel containing ultra-high noise attenuation floating track slab (the GERB system), supported on mechanical springs and highly intolerant to lateral differential movement. Monitoring results demonstrated that lateral movements during piling and subsequent pile loading did not surpass the very tight allowable tolerances (<2.5mm).

Figure 3. 21 Moorfields development approaching completion, with works for separate development above Moorgate box commencing in foreground

Another consideration for practical movement monitoring of completed tunnels (especially in stations,) is the cladding system enveloping the tunnel substrate, which may cover up and render the substrate practically inaccessible for surveyors to monitor in future. It is advisable that infrastructure protection engineers make early representations to cladding system designers and architects to ensure that cladding and the subframes to which they attach, are specified and designed in a manner that allows monitoring equipment such as prisms to be attached without any substantial alterations, and for the cladding not to move differentially to the substrate to which it is attached. This will ensure that monitoring readings from equipment attached to cladding is true also of the tunnel substrate underneath, and furthermore that monitoring can be undertaken relatively easily during the 120-year operating lifetime of the project.

It is far easier and cheaper to intervene at the project design stage rather than later during operation, to incorporate more movement tolerance and adjustment mechanisms, thereby mitigating risk of early (possibly unforeseen) repair and replacement of systems that might run out of movement tolerance during service.

4.2 Risk: Ground movement from Crossrail construction impacts 3rd Party development; Crossrail works impact Commitments to 3rd Party developers

Crossrail Information Paper D12 sets out how Crossrail and its contractors will aim to ensure the impact of ground movement on existing buildings is limited to a level below Damage Category 3 (i.e. not exceeding cosmetic, non-structural damage) as defined by the Burland scale presented in Table 1 of the Information Paper.

This criterion, and the principles of ground movement impact described therein, was extended also to 3rd party developments subject to Crossrail Safeguarding controls, to ensure a consistent approach to impact mitigation.

Thus CRL’s Safeguarding engineering team needed to ensure 3rd party developers were suitably briefed, and without prejudice provided with sufficient technical information about the Crossrail project and its site investigations, to successfully complete their evidence-based assessments for the discharge of their Safeguarding Planning Conditions.

In the early years of Crossrail delivery, CRL published guidelines to enable 3rd party developers commencing works before the commencement of Crossrail tunnelling to estimate and mitigate the predicted ground movement impact arising from tunnelling in the vicinity. The calculation methodology was published in earlier editions of Crossrail Information for Developers and can still be viewed in the Crossrail 2 guidelines (available on the Crossrail 2 Safeguarding website).

In general, monitored actual ground settlements of 3rd party developments during construction of Crossrail works compared well against predictions and it is good to report that for these developments CRL has not to date been alerted to any instances of unforeseen or excessive ground settlement impacts from Crossrail works.

In hindsight with a mind on improvements for future tunnelling projects, it is recommended that from the outset and with senior management support, good working relations and communication mechanisms be established between tunnelling construction teams and the Safeguarding team to best ensure comprehensive understanding and communication of all significant ground movement impacts, including if possible settlement contributions for planned dewatering and other temporary works. It is important for the best assurance of mitigation of ground movement risk that those interfacing with 3rd party developers have clear visibility of all ground movement predictions arising from construction so these can be communicated at the earliest opportunity to best inform developers’ design mitigation. For example it is possible that wells for deep aquifer dewatering may impose additional settlement risk to nearby development.

It is perhaps no surprise that a lot of concurrent 3rd party development concentrated around the stations in the central section of Crossrail. The clients of several adjacent major developments also entered into agreements with CRL which obliged parties to respect each other’s spatial and other interests. Significant efforts to avoid complaints to the Secretary of State and substantial risk were well understood by the CRL teams involved. This was demonstrated in Crossrail’s interface with the 100 Liverpool Street redevelopment, a very large development next to the Broadgate entrance of Liverpool Street which commenced late in the Liverpool Street station construction programme. The property was also the subject of agreements which sought both to protect the existing building and to safeguard its future development. After discussions with the 3rd party development team, it became clear that the initial urban design and planned finished ground levels surrounding the station entrance which were designed to match the profiles of the existing building (as was the baseline assumption) would not work for the new development. Were Crossrail to have proceeded with existing plans, this would have alleviated delivery programme pressures in the short term but at the risk of jeopardising the rightful aspirations of the developers. After recognising the potential consequences for Crossrail, it is a testament to the Liverpool Street station construction delivery team that they assigned budget and resources to address the tricky challenge of revising landscaping levels to tie in, and to engage wholeheartedly with the developer’s construction team to manage and accommodate the complex concurrent construction interfaces through the phases of both projects. The new 100 Liverpool St development fits very well alongside the Elizabeth line station entrance and the resulting urban realm is arguably a vast improvement.

Figure 4 – Photo taken in Feb 2018 from Crossrail’s 1-14 Liverpool St office, showing the Broadgate Ticket Hall glazed canopy in the foreground and the 100 Liverpool St development immediately behind the red site boundary. The photo was taken following demolition, substructure works, utility diversions and start of shell and core construction.

Figure 5 – Photo taken in April 2018 looking westward towards the glazed Broadgate Ticket Hall entrance. Both projects substantially complete.

4.3 Risk: Transmitted groundborne Noise & Vibration from operating Crossrail impacts 3rd Party development

Table 1 in Crossrail Information Paper D10 sets out the project policy and allowances for mitigating transmitted groundborne noise and vibration impact on occupants of buildings alongside the operational underground railway. As with ground movement, the same principles of compliance were adopted, thus CRL imposed Safeguarding Planning conditions, obliging developers to submit evidence demonstrating compliance with IP D10 allowable limits for predicted transmitted groundborne noise & vibration. Crossrail’s published guidance Information for Developers included a methodology for calculating transmitted groundborne noise & vibration impact, to support developers’ submissions. Many development projects were assessed by the Safeguarding team. Evidence would suggest the work put in by developers’ design teams and CRL’s acoustic specialist reviewer has so far mitigated any significant impacts to occupants of developments.

The author attributes a part of this success to having a good working relationship with the CRL Environment team, who afforded the Safeguarding team ready access to acoustic advisors for the purpose of completing assessment of developers’ submissions, and to expand and develop Safeguarding guidance to cover both shallow and deep foundations instances.

4.4 Risks: Crossrail and 3rd Party’s concurrent works impact neighbouring parties and vice versa

Concurrent works were a significant 3rd party interface risk. Under the Safeguarding Direction, CRL were granted rights to recommend Planning Conditions be applied to ensure that its delivery programme would not be impeded by outside party works.

The Crossrail Act 2008 also obliged CRL to take necessary steps to protect 3rd parties from the impacts from Crossrail delivery and to compensate 3rd parties impacted by delivery of the Crossrail works in defined circumstances. There were a number of 3rd party development interfaces, notably above the Bond Street, Tottenham Court Road and Liverpool Street Crossrail stations and at Fisher Street shaft, where it fell to the Crossrail delivery teams and to the Safeguarding team to manage these opposing risks and work with 3rd party developers concerned. The parties took steps to reasonably avoid concurrent ground movement impact on neighbouring properties. to ensure clarity of ownership of ground movement impact and to ensure the best understanding of ground movement (particularly in areas requiring compensation grouting control during tunnelling).

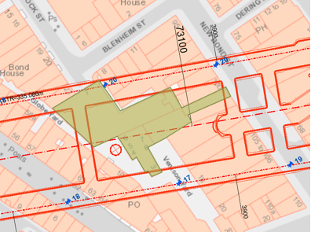

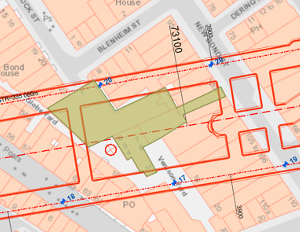

Figure 6 below, taken in September 2012, shows the basement excavation for the extension of Bonhams, 101 New Bond Street, located in the Haunch of Venison Yard. Figures 7 and 8 show that the excavation was very close to Crossrail’s grout shaft BOS2 with its tubes-a-manchettes (TAMs) radiating out from all sides.

Figure 6 – Bonhams basement excavation in Haunch of Venison Yard

Figure 7 – Location of station tunnels below and grout shaft BOS2 within Haunch of Venison Yard

Figure 8: Crossrail grouting TAM array from BOS2 shaft in Haunch of Venison Yard

The new basement (approximately shown by the green footprint on the plan in Figure 7) extinguished the possibility of the Crossrail tunnelling contractor monitoring and correcting ground movement below the footprint using compensation grouting. There were extensive discussions between the CRL Safeguarding engineering team and the 3rd party’s design team, in consultation with the Bond Street station tunnel delivery team, to inform the design and to coordinate the basement delivery programme. This culminated in the developer providing a very stiff raft foundation solution capable of resisting adverse differential settlement arising from the construction of Crossrail tunnels. The basement was also completed in time ahead of scheduled tunnelling, thus largely avoiding the risk of concurrent ground movement impact on neighbouring properties and affording clarity of ownership and responsibility for mitigation of impacts.

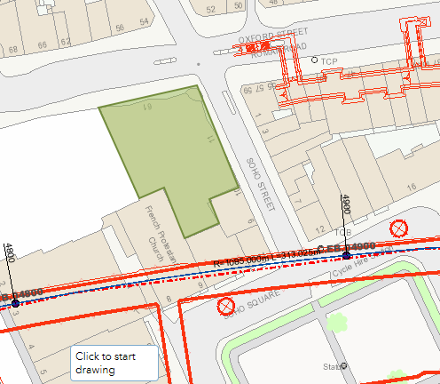

Figure 9 shows the footprint of another development site 61-67 Oxford Street to the north of Soho Square. The development included a deep basement extending approximately 12m below ground level, coincident with the level of Crossrail grout Tube a Manchette (TAM) pipes (not shown) to the north of the platform tunnel which themselves encroached into the development footprint. Notwithstanding mitigating efforts, concurrent programmes conspired to bring the developer’s basement construction programme directly into conflict with Crossrail’s tunnelling and TAM installation programme.

Figure 9 – Development site at 61-67 Oxford Street showing location of Tottenham Court Road station tunnels and Crossrail grout shafts

Whereas Crossrail’s Safeguarding direction and imposed Safeguarding Planning Conditions afforded Crossrail some protection to ensure the developer did not disrupt the Crossrail programme, significant costs resulted from prolongation of the 3rd party developer’s programme. Some lessons from this are:

- The period in the run-up to, and during tunnelling, is generally the most critical for delivery. It is also a time when tunnelling programmes (especially when costly programme-critical controlling dependencies are involved,) are subject to short notice change, and therefore not an entirely reliable basis for planning interfacing works.

- Although the competing demands of a 3rd party development on the programme of a large infrastructure project are a relatively small risk in the grander scheme of major project programme delivery they should be a considered factor in the planning and programming of works to manage risk.

- Without long lead times, which are not necessarily prevalent within the development planning application process, it is more difficult for tunnelling project teams (faced with tight deadlines and massive delay costs), to adapt for new interfacing works at short notice. For example, compensation grouting systems installed to protect the existing urban realm may not be readily adaptable to accommodate late changes to the overburden regime, such as from 3rd parties’ new deep basement construction works. In the case of the aforementioned development the listed French Protestant Church sits on the developer’s site boundary. It had to be protected from the movement impacts of both CRL and the developer’s works. In this instance concurrent tunnelling and basement excavation works would have made monitoring and control of ground movement very difficult. It is not always possible to anticipate the likelihood of converging programmes and conflicting interface works, but if consulted by local Planning authorities prior to Planning approval then Safeguarding teams may with experience, at least have the option to assess and better consider a planning response, which may go as far as recommending refusal (or deferment) of development. This may be preferable to embarking on uncertain and complex interface management at a critical time in project delivery, with potential for significant compensation claims. Such decisions would need to be considered obviously within the context of any existing Undertakings and Assurances, Deeds of covenant or agreements between the parties that might otherwise mitigate the risk.

- Safeguarding engineers should be very wary of development applications planned to be concurrent or near-concurrent with tunnelling. They would be advised to act conservatively and research the construction interface risks carefully and of course reasonably. It is recommended that such research be assisted by legal colleagues and the tunnelling project managers concerned, to afford the best decision making in the interests of all parties. Thus good relationships with construction teams are essential.

4.5 Risk: 3rd Party construction works impact on completed Crossrail infrastructure

The construction (from tunnelling to fit-out) of Crossrail presented significant challenges for the team serving to protect the fledgling infrastructure from the impact of 3rd party development.

At the outset Crossrail did not know how many 3rd party development projects would be encountered and no particular 3rd party developer interfacing work provisions were allowed for in the major delivery contracts. Some out-turn statistics can now be tabled for interest to potentially inform consideration in future projects;

Approx. total number of Planning applications notified to CRL by local Planning authorities across the Central Section 9000 Approx. number of 3rd Party Developer’s planning applications for which conditions were recommended by Crossrail Safeguarding, and for which technical submissions were reviewed for release thereof 240 Approx. number of 3rd Party Developments deemed to impose significant impact risks (as described in Crossrail guidance) and therefore subjected to pre-commencement and post-construction visual defect surveys. 33 Approx. number of 3rd Party Developments deemed to impose greater risk and therefore requiring implementation of intrusive monitoring systems (Manual as well as automatic monitoring) of Crossrail tunnel assets during construction. 12 Table 1 – Quantum of 3rd Party Development interfaces 2009-2021

Tier 1 contract provisions largely excluded scope covering interfacing 3rd party developments (saving those specifically covered by Undertakings and Assurances). As such, Crossrail Investment Authority and Technical approval had to be obtained for all contractors’ support in implementation of in-situ asset protection measures. In hindsight the effort to procure and drive scope change to protect railway infrastructure was resource-sapping. Future major project planners might consider the lessons shared, possibly allowing sums for contractor support (including implementation) of 3rd party in-tunnel monitoring systems, and for facilitating in-tunnel surveys. These allowances could be incorporated into the Geotechnical Baseline Reports of future projects. It is worth noting that costs are likely recoverable from the interfacing 3rd parties utilising the services, thus not adding to the overall cost of the infrastructure project. The Crossrail Safeguarding team raised approximately £1.8M worth of works contract instructions to implement infrastructure protection measures on behalf of developers, at nil cost.

A number of logistical challenges encountered during in-tunnel monitoring are listed below for future awareness and consideration. These not surprisingly had arguably greater impact for developments with long delivery programmes:

- Over several years of construction tunnels evolved from empty concrete shells to the fitted-out overhead line powered railway. Clearly transformation is a major hindrance for tunnel ground movement monitoring systems which function best undisturbed. Significant efforts were made to work with Tier 1 project management teams to reduce the attrition and damage to monitoring equipment but these efforts were only partially successful. This is an important consideration for monitoring.

- Generally, it is most expedient for 3rd parties to implement monitoring themselves, however, for logistical and safety reasons at least, this was not feasible until after completion of tunnelling and completion of installation primary railway systems. Instead, monitoring was either delegated to CRL surveyors or to the Tier 1 contractors.

- Best efforts were made to procure access to tunnels to maintain monitoring equipment and to carry out manual surveys for 3rd parties, but access was quite often delayed or denied in the wake of pressing tunnel delivery activities. Monitoring output (frequency of data reporting and quality of data) also suffered as a consequence. This needs to be considered carefully by developers and infrastructure protection teams alike to best manage and mitigate the risk of periods of interrupted monitoring disrupting development construction.

- Contract handovers (such as from the tunnelling to the railways systems delivery) required re-establishment of working relationships with incoming delivery teams, and renewal of instructions to contractors to support monitoring, especially where monitoring for the 3rd parties was undertaken by the Tier 1 contractors and where handovers resulted also in alterations to power and communication supplies to installed monitoring equipment.

- Both 3rd party and Crossrail delivery programmes experienced changes, meaning that plans and instructions had to adjust accordingly, the consequences of which needed to be managed to mitigate further impacts to each party. It is fortunate that all parties generally were patient and understanding of this, and appreciative of the efforts made to mitigate the impact.

- Successful monitoring depended somewhat on the choice of monitoring equipment. As might be inferred from the list above, automated monitoring was not readily feasible in the early life of tunnels, due to the risk of damage to expensive total stations and the transience of power and comms systems. Optical prisms, preferably within an automated system, have generally proved best all round at recording the true magnitude of tunnel distortions (radial and circumferential distortions) both in the early and later stages of Crossrail delivery. That said CRL has encouraged prescription of systems best matched to developers’ circumstances and also for early warning of aberrant settlement. Automatic wi-fi tilt meters and tiltmeter beams have also been used extensively.

4.6 Risk: 3rd Party works affect Maintenance and Operation

Handover of control of access from Tier 1 contractors to Infrastructure Maintainers of the new Elizabeth line presented challenges to the Infrastructure protection team particularly for procurement of access to continue and to implement monitoring of infrastructure. The challenges are briefly summarised below in the hopes that they may assist others preparing for this phase of implementation on future similar large railway projects;

- The Elizabeth line Central Section tunnels and stations are maintained and operated by two different Infrastructure Management organisations: each with their own access processes and procedures with different timescales.

-

- LU: for Bond Street, Tottenham Court Road, Farringdon, Liverpool St, and Whitechapel stations.

- RfLI: for running tunnels, portals, shafts and tunnel ventilation infrastructure on stations

- RfLI and the operator MTR Elizabeth line for the remaining central area stations -Paddington, Canary Wharf, Custom House, Woolwich and Abbey Wood.

- Additionally the Network Rail IM operational boundary needs to be considered west of Royal Oak Portal/Westbourne Park turnback facility, east of Pudding Mill Lane portal and east of Abbey Wood station.

- While LU procedures were adopted with little change from previous, the RfLI access procedures also differed from Network Rail procedures. This extended the learning curve appreciably.

- During the transition phase, Crossrail contractors retained partial control of access to areas still under completion, testing and commissioning all of which was of high priority to complete delivery of Crossrail and took precedence in many cases.

- The 6 months up to Handover and 12 months after was evidently a period of rapid transformation and evolution of access procedures, as Crossrail morphed from a construction project into an operational railway and as the construction teams gave way to the infrastructure managers. The Infrastructure Protection duty also transitioned from Crossrail to TfL’s IP team with an extended period of embedment of Crossrail’s Infrastructure protection team in support. A very steep learning curve ensued as the team sought to understand railway access planning for the Elizabeth line and then to disseminate knowledge to 3rd party developers needing to implement in-situ protection of the operating railway. The time and effort required to forge working relationships with the various railway access planning communities should not be underestimated. The challenge for infrastructure protection teams, of transitioning in mindset from protection of construction project assets to those of an Operational Railway should also not be underestimated and overcoming the challenges needs to be supported by both the construction project Delivery team and the future operator alike. In the first year after handover infrastructure protection engineers seeking to implement protection on the railway had to spend 60-80% of their time on rail access planning and coordination.

- Inevitably access for 3rd Parties including monitoring contractors, suffered as a number of planned work shifts were rejected or even aborted at very late notice due to misunderstanding or lack of awareness of the new access procedure, problems with coordination and trained safety personnel shortages and of course railway commissioning priorities. These are examples of inevitable challenges to Infrastructure Protection when bringing a new major transport project into service.

- As to what more the Infrastructure Protection team could have done to prepare itself for transition hindsight perhaps it probably would have been beneficial to bring an experienced Network Rail access planner into the team at an early stage with the operational knowledge to better engage with the RfLI rail access planning members in order to cascade this back to the infrastructure protection team and 3rd party developers.

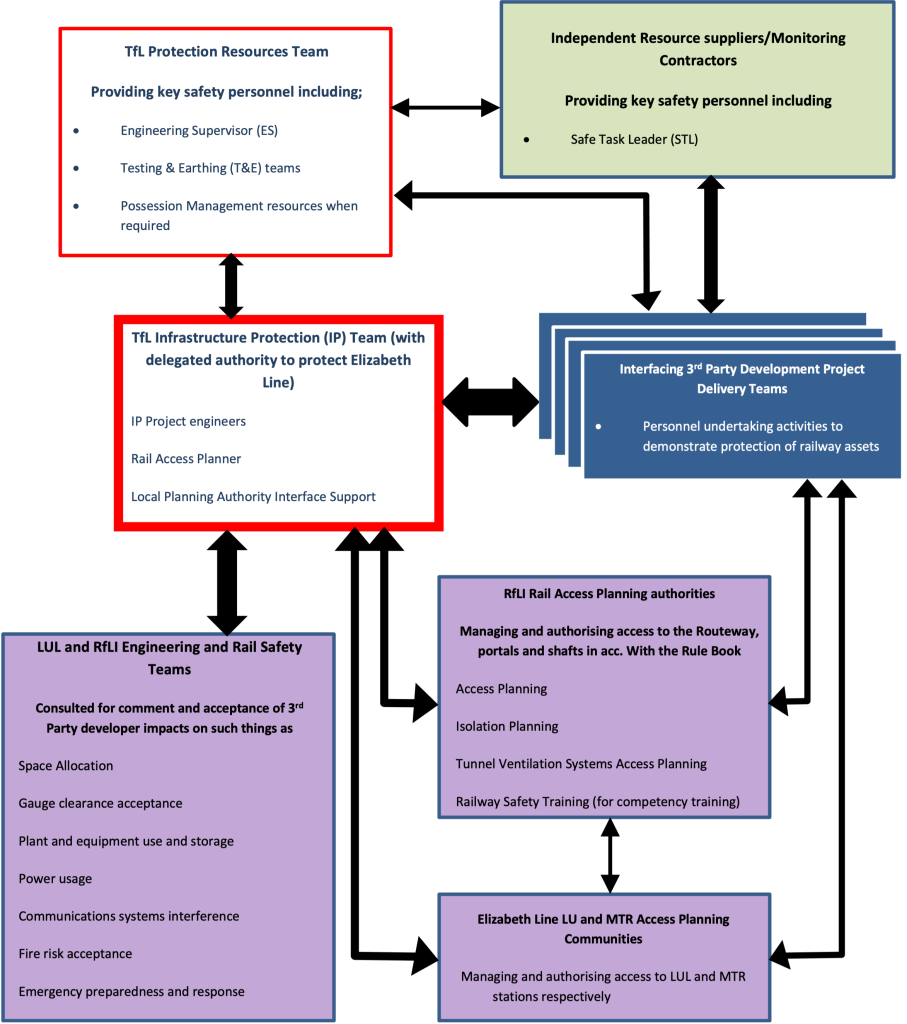

- It is pleasing to report that a steadier, more reliable state of rail access planning has been reached. Figure 4 below depicts the current organisation structure of the Elizabeth line Infrastructure Protection team.

Figure 10 – Communication flowcharts of Elizabeth line Infrastructure Protection with RfLI/LU team for tunnel/station/shaft access/outside parties

5 Conclusions

The Crossrail Safeguarding (Infrastructure Protection) team was kept very busy throughout the 12 year construction programme up to handover of the completed Elizabeth line.

Change and adaptation were constant companions during this time which necessitated fast learning, the setting up of systems for rapid review as well as management, control and monitoring of 3rd party developments and reporting to affected stakeholders, and discipline energy to drive scope change required to implement infrastructure protection and dogma to keep managing the risks.

Success probably pivoted mostly on effective communication and understanding of different parties’ objectives and a willingness to engage and collaborate notwithstanding competitive interest to achieve development goals. It is thanks to the many competent and professional people involved in both the Crossrail and 3rd Party Developers’ teams that goals were largely achieved to mutual satisfaction.

-

Document Links

-

Authors

Geoff Rankin CEng MICE MAPM

Geoff is a chartered Civil Engineer with a background in the planning and design of major infrastructure projects in the UK and abroad. Geoff joined the Crossrail Chief Engineer’s Group in October 2008, initially supporting procurement of the Final Design and Tunnel, Portal and Shaft construction contracts; thereafter Client Package Manager of Contract C122 (Bored Tunnels and Building Damage Impact Assessment), focussing initially on de-risking tunnelling. In 2011 he was given the role of Crossrail’s Third Party Development manager leading a small team with support from disciplines across the Project’s spectrum, to manage and mitigate Crossrail’s ground settlement impact on the built metropolis and its stakeholders, and also conversely, to manage and control the impact of Outside Party developments on Crossrail

Over time Crossrail’s management structure changed in sync with project’s progression. Geoff’s role changed to Crossrail Infrastructure Protection Manager, reporting to the Manager of Engineering. He continued guiding and assuring Outside party development impact, but also managing the Settlement Deeds, managing several survey contracts, and providing technical advice and support to Crossrail’s Insurance team to close out ground settlement claims alleged against the Crossrail project. Geoff’s final years on Crossrail until mid-2022, focussed mostly on the revising infrastructure protection guidance and procedures to align to the Elizabeth line Rule Book and Infrastructure Managers’ access and egress procedures; also on migrating the Infrastructure Protection duty to the TfL Infrastructure Protection team.