Implementing the London Living Wage

Document

type: Case Study

Author:

Andrew Eldred MA, MSc, Anne-Sophie Blin MSc

Publication

Date: 26/02/2016

-

Abstract

This paper describes the steps taken to ensure implementation of the London Living Wage as a minimum hourly rate of pay on the Crossrail programme. It also outlines key lessons learned from this experience, and recommendations for other major project clients who might be considering implementing similar requirements in future.

-

Read the full document

Context

Living Wage Rates

There are currently no fewer than three ‘Living Wage’ rates in the United Kingdom. For the purposes of the present report, the most relevant of these is the London Living Wage, which is a voluntary rate for London set by the Living Wage Foundation. As the table below confirms, the London Living Wage is considerably higher than both the Living Wage National Rate (also set by the Living Wage Foundation and intended to cover the UK outside London), and the minimum statutory rate, recently renamed the National Living Wage.

Rate Status Set By Current Level

(as at April 2016)London Living: London Living Wage Voluntary Living Wage Foundation (calculated by the Greater London Authority) £9.40 Living Wage National Rate Voluntary Living Wage Foundation (calculated by Loughborough University) £8.25 National Living wage (previously the “National Minimum Wage Adult Rate” Voluntary Secretary of State for Business Innovation and Skills (advised by Low Pay Commission) £7.20 [1] Table 1 – UK Living Wage Rates

History

The Living Wage Campaign started in London in the early 2000s. In large part, this was in response to concerns about increased income inequality and in-work poverty, and the negative impact these trends were perceived to be having on particular communities and society more broadly.[1] Living Wages for these purposes are defined as the amount necessary to provide individuals with sufficient earnings over a normal working week of 38½ hours to cover the basic costs of living. [2]

Figure 1 – The Living Wage Campaign began at a meeting of local community leaders, organised by London Citizens (part of Citizens UK), in 2001.

From its early beginnings, the campaign has enjoyed considerable success in persuading organisations

to commit to the payment of Living Wages, not only for their own direct employees, but also to sub-contracted and agency staff. By February 2016, the Living Wage Foundation was reporting over 2000 organisations as accredited Living Wage Employers, including firms of all sizes and from many different economic sectors.

to commit to the payment of Living Wages, not only for their own direct employees, but also to sub-contracted and agency staff. By February 2016, the Living Wage Foundation was reporting over 2000 organisations as accredited Living Wage Employers, including firms of all sizes and from many different economic sectors.Since 2005, the Greater London Authority (GLA) has calculated a separate rate for London on behalf of the Living Wage Foundation, which is known as the London Living Wage. This rate is intended to reflect higher living costs in the capital and is announced annually in November by the Mayor of London during Living Wage Week, on the same day as the Living Wage Foundation confirms the new National Rate.

Relevance of Living Wages for Major Infrastructure Projects

Historically, construction has not been regarded as a low-wage sector [3]. This has meant that implementation of the London Living Wage has tended previously to be regarded as more relevant for ancillary occupations, such as cleaning, catering and security, but less so for construction occupations.[4]

During the sustained economic downturn after 2008, however, many construction workers’ earnings dropped substantially [5]. Furthermore, from 2009 the level of the London Living Wage started to outstrip minimum rates for some lower grades under the Construction Industry Joint Council Working Rule Agreement, negotiated nationally by construction employers and unions. Accordingly, lower-paid construction workers are now considered to be at greater risk of not receiving the London Living Wage than might have been the case before.

Stakeholder interest within the construction industry has therefore increased over time, especially as major projects such as the Olympics and Crossrail have made a public commitment to the London Living Wage as the minimum employment benchmark.[6] Trade unions have launched their own campaigns demanding a Living Wage for construction workers. More widely, the Mayor of London’s objective for the London Living Wage to become the norm by 2020 has helped provide further impetus, raising expectations that construction clients from both the public and private sectors will adopt it on their London projects.[7]

Figure 3 – During the sustained economic downturn after 2008, market rates for some lower-paid construction workers fell below the level of the London Living Wage.

Establishing the requirement

Crossrail’s reasons for adopting the London Living Wage

More than one factor influenced Crossrail’s decision to establish compliance with the London Living Wage as a contractual requirement. These included:

- Organisational considerations. Crossrail is a subsidiary of Transport for London (TfL) which is, in turn, a functional body of the GLA and a living wage employer accredited by the Living Wage Foundation. Although these organisational factors were not enough on their own to bind Crossrail to implement the London Living Wage, they do provide an important part of the context against which that decision was taken.

- The corporate responsibility case. As part of its wider sustainability strategy, Crossrail was committed to demonstrating an ethical approach, together with wider community and social benefits. By helping to address income inequality and in-work poverty, there was clear potential for the London Living Wage to make a valuable contribution to fulfilling these wider objectives (see further ‘Overarching Strategy’, below).

- The business case. In reaching its decision, Crossrail also took account of growing evidence of the potential business benefits of implementing living wages in low-wage sectors. These benefits include reducing staff turnover and boosting productivity, job satisfaction and commitment. [1] [8] [9]

Contractual provisions

Construction activities have accounted for most of the workforce involved in the Crossrail programme, and therefore provided the principal focus for efforts to ensure supply chain compliance with the London Living Wage. Accordingly, Crossrail imposed several contractual requirements as a first step to ensuring compliance. These include requirements on Tier 1 contractors:

- To pay the London Living Wage as a minimum to all their own employees working on the programme;

- To use reasonable endeavours to ensure that their subcontractors also pay the London Living Wage as a minimum on the programme;

- Before issuing site security passes, to check individuals’ remuneration at least meets the London Living Wage;

- To audit subcontractors for compliance with the London Living Wage; and

- To cooperate with Crossrail in resolving any non-compliance with the London Living Wage.

Boundaries

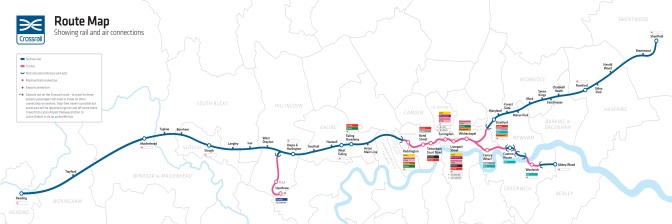

Crossrail has been able to apply these London Living Wage requirements only to those construction works which it and its Tier 1 contractors are delivering directly on the Central Section of the programme (i.e., running from Old Oak Common in the west to Pudding Mill Lane and Plumstead in the east). Other works forming part of the wider Crossrail programme fall outside this Central Section, including:

- Surface works to the west and east of the Central Section, delivered by Network Rail and its supply chain;

- Crossrail-related works carried out by TfL and its contractors (e.g., Bakerloo Line Link);

- Several commercial and/or residential developments mainly associated with Crossrail stations in central London, carried out independently by property companies and their contractors; and

- Other construction work related to the programme, but delivered outside Crossrail’s direct control (e.g., at Canary Wharf Station and the Woolwich Box).

In practice, the Living Wage Foundation has accredited several of the organisations involved in this other work as living wage employers (e.g. TfL, Canary Wharf Group, and a growing number of large London property developers). The present document does not, however, purport to cover how any of these organisations have gone about implementing the London Living Wage on their Crossrail-related works.

Figure 4 – Crossrail’s requirements to contractors to pay the London Living Wage applied only on the Central Section of the Programme. The Central Section broadly overlaps with the main pink section of the partial route map above: running from Old Oak Common (near Paddington) in the west, to Pudding Mill Lane (near Stratford) and Plumstead (near Woolwich) in the east.

Monitoring implementation

Crossrail has employed various mechanisms to ensure Tier 1 contractors monitor and enforce supply chain compliance with the London Living Wage effectively. Most of these mechanisms are rooted in explicit contractual provisions. In addition, a (non-contractual) performance assurance process has played a positive role in motivating Tier 1 contractors to fulfil, and in some cases exceed, base contractual requirements.

Contractor Responsible Procurement Plans

As part of their wider social sustainability obligations under the contract, all Tier 1 contractors are required to submit a Responsible Procurement Plan shortly after contract award. Among other things, these Plans must outline each contractor’s proposed processes for implementing the London Living Wage clauses.

These plans were essential in establishing contractors’ commitment to deliver the social sustainability objectives that were established as part of Crossrail’s wider social sustainability strategy (see ‘Other Legacy Reports’, below). Crossrail has worked closely with contractors to review these Plans at regular intervals, to ensure the objectives and supporting processes (including those relating to the London Living Wage) are kept up to date, relevant and aligned with evolving views on what constitutes good practice.

Contractor induction Checks and Auditing

As described above, Crossrail’s contractual provisions require Tier 1 contractors to check compliance with the London Living Wage before issuing individuals with a site security pass. Typically this check is carried out as part of each contractor’s induction process (hence the term ‘induction checks’). As a further level of assurance, Tier 1 contractors are also required to carry out payroll audits of supply chain employers.

On the (relatively rare) occasions where induction checks or audits have identified a potential non-compliance, Tier 1 contractors are expected to investigate further and, if necessary, implement corrective actions, including payments of back-pay where appropriate.

Contractor Reporting

Supply chain London Living Wage compliance is one of the matters Tier 1 contractors must include in their quarterly Responsible Procurement reports to Crossrail, evidencing their fulfilment of key social sustainability obligations. In these reports Tier 1 contractors declare their estimate of the proportion of each employer’s on-site workforce receiving at least the London Living Wage. They are also asked to state the dates of any audits undertaken.

Performance Assurance

Every six months Crossrail carries out formal assessments of each contract’s social sustainability performance, including Tier 1 contractors’ management of supply chain compliance with the London Living Wage. In line with broader performance assurance principles, Crossrail’s social sustainability team ranks Tier 1 contractors against pre-determined performance criteria. For the London Living Wage, the different performance levels have been defined as follows:

- Basic compliance: the Tier 1 contractor can demonstrate that its own employees are paid the London Living Wage or above, that it has appropriate induction checks in place for all individuals coming to work onsite and a process for auditing supply-chain employers;

- Value-added performance: in addition to the basic compliance criteria, the Tier 1 contractor can demonstrate that it has a robust and proportional approach to managing its supply chain in relation to London Living Wage compliance. This includes, in particular, proactive checks at procurement stage and prior to mobilisation onsite. It also involves a robust approach to auditing, with a particular focus on ensuring that all subcontractors deemed potentially “high risk” (e.g. cleaning, catering, security and labour-only suppliers) are audited regularly throughout the duration of the contract.

- World class performance: in addition to the basic and value added criteria, the Tier 1 contractor (or at least one parent company in the case of joint ventures) can demonstrate support for Living Wages on projects beyond Crossrail, independently of any client requirement.

Resolving implementation issues

Overall, Tier 1 contractors have reported high levels of compliance with the London Living Wage, which have been verified by Crossrail’s own performance assurance assessments. Questions of interpretation and application have nevertheless cropped up from time to time. All these have been resolved, either by referring back to the wording of the contract, seeking guidance from the Living Wage Foundation, or by agreement between Crossrail and the Tier 1 contractors concerned. Below is an account of some of the key practical issues that have arisen and how they have been resolved.

Employers/ employees resident outside London

Enquiries have occasionally arisen about whether the London Living Wage applies only to businesses and individuals resident within the boundaries of the GLA. Both Living Wage Foundation guidance and Crossrail’s own contract clauses have made it clear that the London Living Wage should apply to anyone working on the programme’s London sites, regardless of their home address or the business address of their employer.

Short-term assignments

Initially, some Tier 1 contractors foresaw potential difficulties in guaranteeing compliance with the London Living Wage for individuals coming on site to work intermittently or for short periods. In reality, this has not been a major issue as most such individuals appear to be paid above the London Living Wage any way. Crossrail has recommended a proportionate approach towards this issue, prioritising longer-term and recurrent employers and employees.

Established pay rates below the London Living Wage

Crossrail’s contract has made clear that the London Living Wage is the minimum rate for any hours worked on the programme. Accordingly, it takes precedence over any existing company or industry pay benchmarks, including base rates under the Construction Industry Joint Council Working Rule Agreement, some of which (as explained above) now fall below the London Living Wage. In order to comply with this requirement, some construction employers who normally pay in line with the Working Rule Agreement have supplemented their usual basic rates with a guaranteed hourly bonus, bringing total hourly earnings up to the London Living Wage.

Apprentices

Crossrail has not insisted on contractors paying their apprentices the London Livng Wage. This was a pragmatic decision, based on the need to avoid causing undue disruption to contractors’ existing pay structures (including differentials), and providing some advantages for apprentices themselves (e.g., facilitating transfer between Crossrail and non-Crossrail contracts). It is also in line with Living Wage Foundation guidance that apprentices need not receive the full rate.

Instead, employers have been encouraged to pay at least in line with industry benchmark rates for apprentices, such as those set out in the Construction Industry Joint Council Working Rule Agreement. In practice, some apprentices on advanced and higher apprenticeship programmes have received rates of pay at or above the London Living Wage.

Figure 5 – The London Living Wage does not normally apply to apprentices. Crossrail has nevertheless encouraged contractors to pay above National Minimum Wage apprentice rates.

Overtime, Bonuses, Expenses and Benefits

Most construction operatives work in excess of the 38½ hours per week on which the London Living Wage is calculated. This has prompted the question of whether employers could continue to pay below the London Living Wage for basic guaranteed working hours but make up the shortfall using overtime premium payments well in excess of the London Living Wage (such as those set out in the Construction Industry Joint Council Working Rule Agreement).

Crossrail rejected the practice of generating an artificial ‘average’ hourly rate by taking account of higher overtime earnings. For one thing, this was inconsistent with the wording of the contract (which requires the payment of London Living Wage for any hour worked on the programme). Secondly, advice received from the Living Wage Foundation confirmed that Living Wages are predicated on the principle that individuals should not need to work overtime in order to meet basic needs.

Crossrail and Tier 1 contractors have further agreed that bonus payments should count towards the London Living Wage only if they are effectively guaranteed (i.e. paid consistently every week, rather than being discretionary or contingent on meeting production targets, etc.). Similarly, it has been agreed that daily travel and overnight subsistence payments (relatively common in construction) ought not to be included in the calculation.

Holiday pay, pension contributions and other benefits which cannot normally be included in calculations for National Minimum Wage compliance also do not count towards the London Living Wage.

Implementation date

As has been seen, the Mayor of London announces the annual increase to the London Living Wage each November. Neither the Mayor nor the Living Wage Foundation sets a hard-and-fast deadline for implementing the increase across supply chains, which often tend to be postponed until supplier contracts come up for renegotiation. This option is not available in a construction context, and so soon after the Mayor’s announcement, Crossrail has issued a formal communication to all Tier 1 contractors notifying them of the change. In line with general practice within the GLA group, Tier 1 contractors have then been given until April the following year to implement the new rate, including cascading the communication down through their own supply chains.

Figure 6 – The Mayor of London announces the new London Living Wage rate in November 2015. Employers on Crossrail have until 1 April 2016 to implement the new rate.

Lessons learned and recommendations for future projects

As well as the practical implementation issues outlined above, experience on Crossrail has highlighted some broader lessons about the client’s role in ensuring compliance with the London Living Wage and similar requirements. These are considered below, including three related recommendations for clients on future major infrastructure projects. In addition, one further recommendation is included for consideration by the Living Wage Foundation and its members.

Ensuring appropriate allocation of roles and responsibilities

Some Tier 1 contractors began by interpreting their London Living Wage obligations as a supply chain management or corporate responsibility issue, and as such a matter for their procurement, sustainability or community relations teams to manage.

Although understandable up to a point, the potential drawbacks of such an approach included (a) insufficient attention to monitoring and enforcement in a few early cases, and (b) a disconnect between London Living Wage implementation and Tier 1 contractors’ control processes over other supply chain employment practices, managed by employment relations specialists.

Encouraged by close collaboration between Crossrail’s own social sustainability and employment relations functions, all contracts eventually adopted a joined-up approach to supply chain employment practices, which future projects could seek to establish from the outset.

Recommendation 1: Rather than treating Living Wages as a stand-alone requirement, clients should consider integrating the Living Wage more closely with other provisions relating to supply chain employment relations (e.g., employment status, freedom of association, industry collective agreements, payroll auditing, employee whistleblowing, etc.).

Supplementing core contractual provisions

As has been already explained (in ‘Resolving Implementation Issues’, above), numerous questions arose during the course of the programme which it was not always possible to resolve simply through interpretation of the (rather succinct) wording used in Crossrail’s Tier 1 contracts. Furthermore, not all Tier 1 contractors’ initial processes to monitor and enforce compliance were as effective as they might have been. Instances where the quality of these processes varied quite significantly included:

- The wording of the Living Wage question on induction forms;

- Safeguards to ensure an individual’s identity remains confidential in the event they declare that they are not receiving the Living Wage;

- Measures for scrutinising subcontractors’ employment practices during procurement and/or prior to mobilisation onsite;

- Payroll auditing.

Crossrail was able to work through all these issues collaboratively with Tier 1 contractors, assisted to a significant degree by the voluntary performance assurance process. This eventually brought about greater consistency of practice across the programme, although in future clients might prefer to embed these shared understandings and good practice processes at the outset. Given variability in contractor performance, clients might also want to consider reserving the right to conduct their own payroll audits of lower-tier suppliers as a way of supplementing Tier 1 contractors’ own processes.

Recommendation 2: In addition to core contractual provisions, it would be helpful for clients in the future to provide supplementary information, confirming their expectations of good practice with regard to contractors’ monitoring and enforcement of compliance. Such information might also include clarification of key issues of interpretation (e.g., those highlighted in ‘Resolving Implementation Issues’, above). Preferably all this information should be included in a broader employment relations Code of Practice, issued with the contract and incorporated into it. Clients should also consider reserving the right to carry out their own payroll audits.

Managing London Living Wage compliance on ancillary contracts

As well as its main construction contracts, Crossrail procured a wide variety of ancillary services (e.g. archaeological works, legal services, management consultancy, and some facilities management). In the interests of consistency, a question about London Living Wage compliance was included during the procurement of these services, and the same clause incorporated into commercial contracts.

Monitoring compliance in these circumstances was always likely to prove difficult from a resourcing perspective, however. Moreover, close monitoring seemed disproportionate in many cases, given the comparatively low value of some contracts, work being performed in remote locations away from any Crossrail premises, and the minimal risk in some cases of actual pay rates falling below the London Living Wage (e.g., in contracts for professional services). Higher-risk contracts were relatively rare: for example (and in contrast to some other projects), nearly all security work on Crossrail was procured by Tier 1 contractors rather than by Crossrail itself.

For these reasons, Crossrail adopted a proportionate, risk-based approach to monitoring London Living Wage compliance on ancillary contracts, focussing principally on those areas where the perceived risks were greatest.

Recommendation 3: Clients should bear in mind all types of procurement when considering Living Wage policies. There are considerable advantages to be gained from close communication between the corporate procurement function and the team responsible for Living Wage implementation, and adopting a proportionate, risk-based approach to monitoring compliance in relation to such contracts.

Figure 7 – Archaeology was one of Crossrail’s most important non-construction procurements. MOLA, the successful contractor, pays all its personnel (including short-term hires) at or above the London Living Wage

Testing the business case for paying Living Wages

It has already been explained that the factors Crossrail took into account before deciding to mandate the London Living Wage included the evidence then available of potential business benefits in paying Living Wages, such as lower staff turnover and higher productivity, job satisfaction and commitment (see ‘Establishing the Requirement’, above ).

Since then, however, comparatively little attention has been devoted to testing these purported benefits on the Crossrail programme itself. Partly, this is because Crossrail has procured very little work from low-paying sectors directly, and so has had no immediate interest in measuring absolute or relative performance. Instead, Crossrail has focussed mostly on the compliance and reputational dimensions of enforcing the London Living Wage (as outlined above), rather than any associated business benefits.

Anecdotally, however, some security subcontractors on the programme are understood to have reported advantages from paying the London Living Wage, including lower staff turnover and a greater flexibility around shift arrangements. As part of the Learning Legacy, therefore, Crossrail plans to produce a further report, the purpose of which will be to highlight real-life examples where the London Living Wage appears to have had a positive impact on the programme, as well as other instances (if any) where the expected benefits have not materialised (see ‘Other Legacy Reports’, below).

Nevertheless, with the benefit of hindsight, Crossrail accepts that more could have been done to track the London Living Wage’s impact from the start of the programme. This is therefore something which future projects should contemplate putting in place.

Recommendation 4: As well as considering potential business benefits as part of an initial decision to mandate the payment of Living Wages, future projects should give serious consideration to setting up processes for capturing evidence systematically of their actual impact (whether positive, negative or neutral). Given the increased incidence of low pay among parts of the construction workforce, this should include evidence of the impact of Living Wages on relevant construction activities, as well as more traditional areas such as catering, cleaning and security.

Extending the ‘Living Wage Employer’ accreditation to encompass construction projects

Although some construction clients, including Crossrail and the Olympic Delivery Authority, have opted to incorporate compliance with the London Living Wage into their contracts, this is not currently a precondition for accreditation as a Living Wage Employer by the Living Wage Foundation. Although accreditation typically requires organisations to extend Living Wages to supply chain employees based on their ‘premises’ (e.g., cleaning, catering, security and temporary agency workers), construction projects seem to be mostly excluded from this principle. This is because on such projects the Living Wage Foundation often deems a construction site to be the ‘premises’ of the main construction contractor, rather than the client organisation.

Whilst it is understandable that the Living Wage Foundation needs to draw a line somewhere, arguments in favour of taking account of organisations’ behaviour in their role as construction clients include:

- The dividing line between construction activities, repair and maintenance and facilities management is not always a clear one;

- Construction works will often take place within or near a client organisation’s ‘premises’ (e.g., the renovation or extension of an existing office, factory or store);

- Client organisations on some projects play a direct role in procuring and/or managing construction works (either with or without specialist support from a construction management contractor);

- Unless clients establish a level-playing field by incorporating Living Wages into their contracts, construction contractors who bid on the basis of Living Wages are at risk of losing out to others on cost grounds;

- Perhaps as a consequence of the preceding point, take-up of the Living Wage Employer accreditation among construction contractors remains low;

- As we have seen, pockets of low pay have now emerged in parts of the construction labour market (see ‘Context’ above).

Accordingly, the final recommendation is that the Living Wage Foundation should consider developing further clarification and best practice guidance in relation to construction projects.

Recommendation 5: Clients such as Crossrail and the Olympic Delivery Authority have shown how Living Wage requirements can be implemented successfully on construction projects. In order for these isolated initiatives to become the norm, however, the Living Wage Foundation should consider developing further clarification and best guidance in relation to construction projects. Such clarification/ guidance could be helpful in defining circumstances where the Foundation’s accreditation criteria already capture organisations acting in their capacity as construction clients. It could also set out an improved process for encouraging take-up of the Living Wage accreditation among construction contractors – possibly through the Foundation’s existing Service Providers Recognition Scheme, or something similar.

Other Learning Legacy items

It is also useful to bear in mind that Crossrail’s London Living Wage requirements constitute one element of a broader set of employment and skills provisions, which in turn have formed part of an overarching Sustainability Strategy. Further information about this wider context is available via the following Crossrail Learning Legacy publications:

- Skills and Employment Strategy

- Social Sustainability Performance Assurance Framework

- Social Sustainabilty Working Group

- Sustainability Strategy

- Construction Employment Relations – including more in-depth consideration of auditing and other mechanisms for assuring supply chain employment practices (to be published in 2018).

References

[1] Wills, J. and Linneker, B. (2012) The Costs and Benefits of the London Living Wage – Queen Mary, University of London and Trust for London

[2] GLA Economics (2013) A Fairer London: The 2013 Living Wage in London – Greater London Authority

[3] Office for National Statistics (2014) Patterns of Pay: Estimates from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, UK, 1997 to 2013 – ONS

[4] Wills, J. (2001) Mapping Low Pay in East London – TELCO

[5] van Wanrooy, B., Bewley, H., Bryson, A., Forth, J., Freeth, S., Stokes, L. and Wood, S. (2013) Employment Relations in the Shadow of Recession: Findings from the 2011 Workplace Employment Relations Survey – Palgrave Macmillan

[6] Regan, P. (2012) Negotiating the Citizens Agenda for Wages, Training and Employment – Olympic Delivery Authority

[7] GLA Economy Committee (2014) Fair Pay: Making the London Living Wage the Norm – Greater London Authority

[8] Sokol, M. Wills, J. Anderson, J. Evans, Y. Buckley, M. Frew, C and Hamilton, P. (2006) The Impact of Improved Pay and Conditions on Low-paid Urban Workers: the Case of the Royal London Hospital – Queen Mary, University of London

[9] Wills, J. Kakpo, N. and Begum, R. (2009) The Business Case for the Living Wage: the Story of the Cleaning Service at Queen Mary – Queen Mary, University of London

[1] The Chancellor of the Exchequer’s announcement of the ‘National Living Wage’ in November 2015 means that from April 2016 the UK will have five different statutory minimum rates of pay, as follows:

- National Living Wage – payable to workers aged 25 or above;

- National Minimum Wage Adult Rate – payable to workers aged between 21 and 24;

- National Minimum Wage Youth Rate – payable to workers aged between 18 and 20;

- National Minimum Wage Youth Rate – payable to workers aged under 18; and

- The National Minimum Wage Apprentice Rate – payable to apprentices aged between 16 and 18, and those aged 19 or over who are in their first year.

-

Authors

Andrew Eldred MA, MSc - Crossrail Ltd

Andrew Eldred was Head of Employee Relations at Crossrail until early 2017. His responsibilities included trade union engagement, oversight of contractors’ management of site employment relations, and delivery of apprenticeships and other skills and employment commitments. Before joining the Crossrail programme, Andrew held several senior employment relations roles in construction, including three-and-a-half years as the ODA Delivery Partner’s Industrial Relations Manager on the London 2012 Olympic Park construction programme. He holds an MA in Modern History from the University of Oxford and an MSc in Human Resource Management from Birkbeck College, London.

Anne-Sophie Blin MSc

Anne-Sophie Blin was the Lead Social Sustainability Officer at Crossrail from 2013 to end of 2016. In this role, she oversaw the implementation of the Crossrail Social Sustainability strategy, working with contractors to ensure they fulfilled their contractual obligations in relation to job creation, skills developments, promoting equality and diversity, and enforcing the London Living Wage. Before joining Crossrail in 2013, Anne-Sophie advised international property companies on developing and implementing strategies covering environmental and economic as well as social sustainability. She holds an MSc in Urbanisation and Development from the London School of Economics and a Master’s degree in International Relations from Sciences Po, Paris.

-

Peer Reviewers

Michael Kelly MICRS, Chair, Advisory Council Living Wage Foundation

Julie Thornton, Head of HR, Tideway

Scott Young, Head of Skills and Employment, Tideway