Achieving Social Sustainability Objectives Through Performance Assurance

Document

type: Micro-report

Author:

Anne-Sophie Blin MSc, Andrew Eldred MA, MSc

Publication

Date: 14/03/2017

-

Abstract

In 2012 Crossrail introduced six Performance Assurance Frameworks (PAFs), intended to ensure that Tier 1 contractors met, and preferably exceeded, their minimum contractual obligations. The present paper examines Crossrail’s application of the PAF approach in assuring contractors’ management of Social Sustainability. It explains the context for the initial development of a Social Sustainability PAF in 2012 and why substantial revisions were made to the PAF contents and assessment process in 2014. It ends with an overview of the main outcomes, lessons learned and recommendations and would be relevant to any major project looking to develop their approach to social sustainability.

-

Read the full document

1. BACKGROUND

Performance Assurance Frameworks (PAFs) have been a distinctive part of Crossrail’s approach to maximising Tier 1 contractors’ performance on the project. There have been six of these in all, each covering a different field of activity. Section 6 at the end of the report identifies other Legacy reports for sources of information about the Crossrail PAF regime generally.

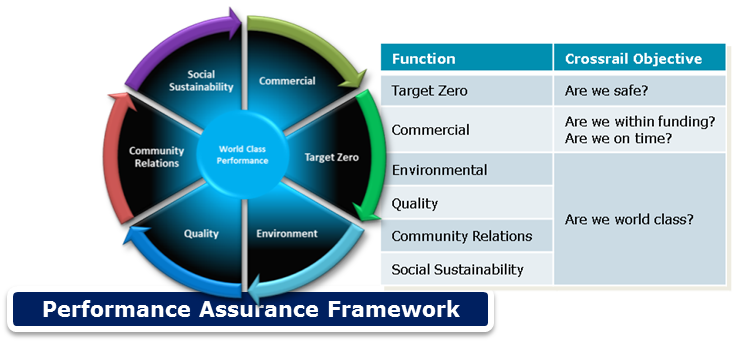

Figure 1 – Social Sustainability included in Performance Assurance Framework

This report concentrates on the development, implementation and modification of the Social Sustainability PAF, which was one of the suite of six developed from its inception in 2012 to the final assessment in January 2016. Like the other five PAFs, the Social Sustainability PAF has three main features:

a) Use of both leading and lagging indicators of performance. For PAF purposes, these have been defined, respectively, as:

• Inputs (i.e. quality of systems, processes, policies and procedures); and

• Outputs (i.e. traditional, quantitative KPIs)

b) Four, defined levels of performance – namely:

• Non-compliant: the Tier 1 contractor does not comply with the requirements of the contract;

• Basic compliance: the Tier1 contractor complies with the requirements of the contract;

• Value-added: the Tier1 contractor demonstrates performance above minimum contractual requirements;

• World-class: the Tier 1 contractor demonstrates industry-leading performance.

c) Regular assessments of Tier 1 contractors’ performance against PAF criteria. In the case of the Social Sustainability PAF, these assessments have taken place every six months, between January 2013 and January 2016.

The next three sections focus in turn on: (i) the contents of the Social Sustainability PAF; (ii) the assessment process; and, (iii) the main performance outcomes.

2. CONTENTS OF THE SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY PAF

2.1 Contractual requirements

As with the other PAFs, the provisions of Crossrail’s contract with Tier 1 contractors formed the main starting point for designing the original Social Sustainability PAF back in 2012. For present purposes, the contractual provisions were located in the ‘Responsible Procurement’ section (Part 15) of Crossrail’s Works Information. These embody a wide range of priorities, mostly linked to Crossrail’s Skills and Employment Strategy, launched in 2010. Under the Responsible Procurement provisions, each Tier 1 contractor has been required:

a) To meet numerical ‘Strategic Labour Needs and Training’ (SLNT) targets, calculated according to the tendered value of the contract (e.g., job starts, apprenticeships, work placements, etc.);

b) To use the Crossrail Jobs Brokerage to advertise all vacancies on the project, including vacancies with lower-tier supply chain employers;

c) To implement the London Living Wage as a minimum rate of pay for its own employees, and ensure that supply chain employers do likewise;

d) To take steps to encourage equality and diversity, including registration with the Diversity Works for London website and delivery of workforce diversity training;

e) To adopt measures to encourage supply chain diversity, including encouraging greater representation of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and advertising relevant procurement opportunities through the ‘Compete For’ web portal;

f) To draw up a Responsible Procurement Plan, setting out how it intends to fulfil each of the above requirements;

g) To report on progress to Crossrail every quarter.

Figure 2 – 2010 Skills and Employment Strategy

2.2 PAF Version 1 (2013 to 2014)

After consulting Tier 1 contractors during 2012, Crossrail launched the first version of its Social Sustainability PAF in January 2013. This original version remained the basis for assessing contractors’ Social Sustainability performance over the next two years, involving four assessment rounds in all. Distinctive features of PAF Version 1 included:

a) Incorporation of the full range of ‘Responsible Procurement’ requirements into the PAF. This meant that procurement matters (i.e., SME participation) were assessed alongside skills and employment matters (e.g., SLNT targets, London Living Wage, equality and diversity).

b) A greater emphasis on Output rather than Input measures of performance. Whilst PAF Version 1 incorporated some measures of Input performance, these did not extend much beyond the basic contractual requirements to develop a Responsible Procurement Plan and report quarterly on progress. Much greater prominence was afforded to Output measures, especially those relating to contractors’ delivery of numerical SLNT targets.

c) A limited conceptualisation of Value-Added and World-Class performance levels. These were defined principally in quantitative terms (e.g., delivering more job starts, apprentices, work placements, etc. than the contractual SLNT target). This approach further underlined the bias in PAF Version 1 towards lagging/ Output indicators of performance rather than leading/ Input indicators.

To a large extent, (a) to (c) above reflected the context within which PAF Version 1 was created. First, there was the fact that Crossrail’s principal objective in these early days was to ensure that contractors at least fulfilled their numerical SLNT targets – thereby enabling Crossrail to meet its own publicly stated commitments on job starts, apprenticeships, work placements, etc.

Secondly, and more generally, Crossrail had few fixed ideas initially about how Tier 1 contractors should go about fulfilling their SLNT targets and other ‘Responsible Procurement’ obligations; nor was it clear what Value Added or World Class Input performance might look like. Most contractors’ Responsible Procurement Plans were also quite sketchy on these points, whilst Crossrail staff involved in developing the PAF came predominantly from a procurement background, with little direct knowledge or experience of skills and employment issues. Accordingly, Crossrail was initially reluctant to put forward suggestions of its own about what ‘good’ or ‘best’ practice might look like.

2.3 Transition to PAF Version 2 (2014)

As shall be seen later (in ‘Performance Outcomes’, section 4), PAF Version 1 achieved a considerable degree of success. Nevertheless, as successive assessments were completed there was a growing consensus among both Crossrail and Tier 1 contractors that this Version could and should be improved upon. By 2014 seven issues in particular were thought to require attention.

a) Tackling weaknesses in contractors’ management processes

As explained above, many Tier 1 contractors’ early Responsible Procurement Plans failed to provide much detail about the processes they intended to adopt in order to fulfil their Social Sustainability obligations. During successive PAF assessment rounds in some cases it was found that contractors’ actual management processes differed from those set out in their Plans. For Crossrail, this suggested a need to incorporate more explicit Input performance measures into the PAF, in order to balance and support the existing Output measures.

b) Highlighting and sharing examples of good practice

At the same time as uncovering bad practice, PAF assessments also revealed examples of good and even exceptional practice. Both Crossrail and the Tier 1 contractors concerned were eager to highlight and share these examples with others. To facilitate this, Crossrail started to develop more detailed definitions of Value-Added and World-Class Input performance for each subject area, with a view to incorporating these eventually into a revised PAF.

c) Attaching greater weight to quality issues, especially in relation to apprenticeships

Both Crossrail and individual Tier 1 contractors were eager to ensure that the drive to hit numerical SLNT targets should not come at the expense of quality. This issue was felt to be particularly relevant for apprenticeships, where certain indicators of quality already enjoyed widespread acceptance (e.g., effective recruitment and mentoring processes, low drop out rates, high levels of post-completion employment). For Crossrail, the logical next step was to incorporate these indicators into a revised PAF.

Figure 3 – Contractors’ delivery of apprenticeships

d) Placing more emphasis on supply chain engagement

In the early days many contractors did not focus on the contractual obligation to maximise SLNT and other opportunities among their subcontractors and labour suppliers. For Crossrail by 2014 this was a priority to address, especially with the imminent start of the building and fit-out phase of the project, during which supply chain employers could be expected to account for a far higher proportion of the total site workforce than during the earlier tunnelling and civil engineering phase. Accordingly, Crossrail decided to incorporate more explicit requirements as part of a revised PAF, both in order to ensure Tier 1 contractors at least complied with their contractual obligations to involve their supply chains, and to promote some (at the time comparatively rare) examples of good practice.

e) Bridging the gap in equality and diversity requirements

As early as 2013 Tier 1 contractors were reporting difficulties in accessing the Diversity Works for London website (the main portal for carrying out the self assessments required to obtain a rating against the Diversity Works for London standard). By 2014, it was clear that issues with Diversity Works for London were creating a gap in Tier 1 contractors’ equality and diversity obligations under their contracts with Crossrail.

Crossrail concluded that at this comparatively late stage it would be impracticable to adopt a new external standard or to develop and administer one of its own. Instead, the Social Sustainability team decided to focus on using a revised PAF to encourage Tier 1 contractors to adopt some relatively simple, practical measures at site level. After consultation with contractors, these were finalised to include steps to address specific, everyday diversity and inclusion challenges, targeting employment and skills opportunities towards historically under-represented groups, and promoting respect.

f) Improving support for Crossrail employability initiatives

Although PAF Version 1 contained references to the Crossrail Jobs Brokerage, these framed Tier 1 contractors’ performance principally in Output terms as the mathematical ratio between the number of vacancies advertised and the number ‘converted’ into jobs for Brokerage candidates. However there were instances of inconsistent compliance with the requirement to advertise all vacancies through the Brokerage, and difficulties in measuring and influencing job outcomes (most of which were controlled by supply chain employers rather than Tier 1 contractors themselves).

After consultation with Tier 1 contractors and the Brokerage, Crossrail’s Social Sustainability team decided to move away from ‘conversion rate’ targets, and to prioritise instead new Input criteria, based on steps the Brokerage and some Tier 1 contractors were already taking to improve buy-in among subcontractors and labour suppliers. In addition – and as a further support for equality and diversity – new PAF World Class criteria were developed to encourage Tier 1 contractors to participate in employability initiatives then being piloted by the Brokerage. Among other things, these included partnerships with Buildforce (injured ex-service personnel) and Women Into Construction.(references to be included).

Figure 4 – Women into Construction

g) Resolving teething issues relating to the PAF itself

Inevitably, some teething issues cropped up as PAF Version 1 was rolled out across the project. Some of these issues related to aspects of the assessment process (see fsection 3.1, below). On the content side, Tier 1 contractors questioned the inclusion of supply chain diversity, which they felt belonged more naturally as part of Crossrail’s Commercial PAF rather than the Social Sustainability PAF.

After an initial period of consultation in late 2013, Crossrail worked up a proposed new PAF criteria in draft. These were discussed further with Tier 1 contractors, and refined. To facilitate a smooth transition, Crossrail offered Tier 1 contractors the option to undergo a ‘mock’ assessment under the new criteria in autumn 2014. This proved helpful not only in identifying further refinements to the PAF itself, but also highlighting just how far many contractors still had to go in order to comply with the revised requirements (see section 4).

2.4 PAF Version 2 (2015 to 2016)

After the mock assessments in autumn 2014, the first formal assessment using PAF Version 2 took place in early 2015. So far two further assessments have taken place, in mid-2015 and early 2016. Key elements that have changed/developed/were highlighted were:

a) Communicating priorities

In order to communicate Crossrail’s strategic priorities as clearly as possible, PAF Version 2 performance criteria were grouped around four key areas, listed below. For each area, the PAF included a vision statement, describing in simple terms what contractors need to do in order to reach World Class levels of performance.

Performance Area Vision Statement Strategic Labour Needs and Training (SLNT)

‘The Contractor maximises SLNT opportunities through strategic planning, effective engagement with the supply chain and the Crossrail Jobs Brokerage team. Through its corporate apprenticeship scheme and by working closely with its key subcontractors, the Contractor aims to influence the qualitative standards of apprenticeships for the construction industry in a positive manner.’ Equality and Diversity

‘The Contractor takes a proactive stance in considering what equality and diversity mean for a site-level environment and is taking action to address key challenges.’ London Living Wage

‘Processes in place in relation to the London Living Wage are robust and followed through in a systematic manner from procurement through to contract management.’ Delivery of Social Sustainability

‘Social Sustainability is managed effectively through strategic planning and clear allocation of responsibilities at site level. The Contractor works closely with its supply chain and develops its capability in relation to Social Sustainability, influencing how similar requirements are implemented on future projects.’ Table 1 – PAF Version 2 performance areas and vision statements

b) Performance criteria

The following tables pick out selected examples of the performance criteria used in PAF Version 2. This is intended to illustrate how these criteria were designed to address both Crossrail’s core Social Sustainability requirements and the additional priorities which emerged during 2013-14. PAF Version 2 details these requirements.

i. Strategic Labour Needs and Training (SLNT)

The main change was to balance PAF Version 1’s focus on numerical SLNT outputs with broader qualitative criteria, including supply chain engagement, apprenticeship quality and support for the Crossrail Jobs Brokerage.

Priorities Basic Compliance criteria Value Added criteria World Class criteria Meeting/ surpassing contractual targets T1 on track to deliver minimum contractual targets T1 on track to deliver ‘stretch’ apprenticeship target T1 supporting Brokerage work placement initiatives (e.g., Women into Construction) Supply chain provision of skills and employment opportunities T1 seeks to involve subcontractors in delivery of apprenticeships and other SLNT initiatives T1 sets explicit apprenticeship targets with subcontractors (preferably contractually binding) T1 takes account of work package characteristics when setting subcontractor targets (e.g. maximising apprenticeship opportunities on labour-intensive subcontracts) Apprenticeship quality T1 has training plans in place for own apprentices T1 demonstrates good practice in operation of own apprentice scheme (e.g., effective recruitment, mentoring, high retention rates, etc.) T1 promotes good practice apprenticeship standards among subcontractors Employer support for the Crossrail Jobs Brokerage T1 and subcontractors advertising vacancies through Brokerage T1 facilitates direct contacts between subcontractors and Brokerage T1 uses Brokerage to advertise job vacancies outside the Crossrail project and/or to source candidates for apprenticeships, work placements, etc. Table 2 – PAF Version 2 revised SLNT performance criteria

ii. Equality and Diversity

The priority was partly to replace the Diversity Works for London standard by encouraging contractors to adopt simple and practical initiatives at site level to address under-representation and/or disadvantage.

Priorities Basic Compliance criteria Value Added criteria World Class criteria Effective E&D policies T1 ensures subcontractors have E&D policies in place T1 identifies and addresses specific site-level E&D challenges (e.g. language issues) T1 encourages subcontractors to target traditionally under-represented groups (e.g. through support for Brokerage work placement initiatives) Effective E&D training T1 provides E&D training to site-based managers T1 implements appropriate E&D training and/or engagement programmes for whole site workforce T1 implements respect initiatives on site Table 3 – PAF Version 2 revised Equality and Diversity performance criteria

iii. London Living Wage

The main objectives were to remove any uncertainty about the level of checks necessary to comply with contractual requirements, and to encourage contractors to adopt additional measures, up to and including support for living wages outside the Crossrail project.

Priorities Basic Compliance criteria Value Added criteria World Class criteria Effective assurance T1 passes LLW requirements down to its subcontractors and has adequate induction checks and auditing processes in place T1 implements specific good practice principles in relation to early supply chain engagement, induction checks, auditing, remedial actions, and communicating LLW annual increases T1 supports living wage compliance outside of the Crossrail project Table 4 – PAF Version 2 revised London Living Wage performance criteria

iv. Delivery of Social Sustainability

The desire was to make the contract-level processes and resources required for contractors to fulfil their Social Sustainability commitments effectively more explicit than before.

Priorities Basic Compliance criteria Value Added criteria World Class criteria Effective planning T1’s Responsible Procurement plan approved by Crossrail T1 regularly reviews and updates its Plan T1 embeds Plan into procurement and commercial processes Clear roles and responsibilities T1 has a Responsible Procurement Representative in place and defines the relevant roles and responsibilities of others on the contract T1 implements own performance improvement plan in response to PAF assessment recommendations T1 demonstrates senior buy-in and involvement of other functions in achieving objectives (e.g. procurement/ commercial) Effective supply chain management T1 passes requirements down and monitors supply chain compliance T1 tailors approach depending on work package/ subcontractor characteristics T1 adopts specific initiatives to engage supply chain (e.g., performance management, reward and recognition) Table 5 – PAF Version 2 revised Delivery of Social Sustainability performance criteria

3. THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS

Having outlined the contents of the Social Sustainability PAF, this section will now describe how Crossrail and its Tier 1 contractors have operated the assessment process. The following table summarises the main stages of this process. Whilst there have inevitably been some modifications and refinements over time, the essential features of the PAF assessment process have remained broadly the same since 2013.

Stage Description 1. Submission of evidence Crossrail invites each Tier 1 contractor to submit evidence of its progress in relation to PAF requirements one month ahead of a review meeting. This evidence needs to relate to activity during the six-month period covered by the assessment, and is in addition to Social Sustainability reports which each contractor should already have supplied for the preceding two quarters. 2. Scoring

The Crossrail Social Sustainability team reviews the evidence, scoring each contractor against the PAF performance criteria and making recommendations on how the contractor might improve its scores in future. Draft scores and recommendations are then forwarded to the contractor, ahead of the review meeting. 3. Review meeting This meeting is usually attended by a member of Crossrail’s Social Sustainability team and the Tier1 contractor’s Project Director and Social Sustainability lead. Representatives of Crossrail’s Delivery function (e.g., the Project Manager or his/ her nominee) are also encouraged to attend.

At the review meeting, participants typically discuss the draft scores and recommendations, including any areas of disagreement. After the meeting, the contractor is given another month in which to submit evidence supporting any change to the draft scores.

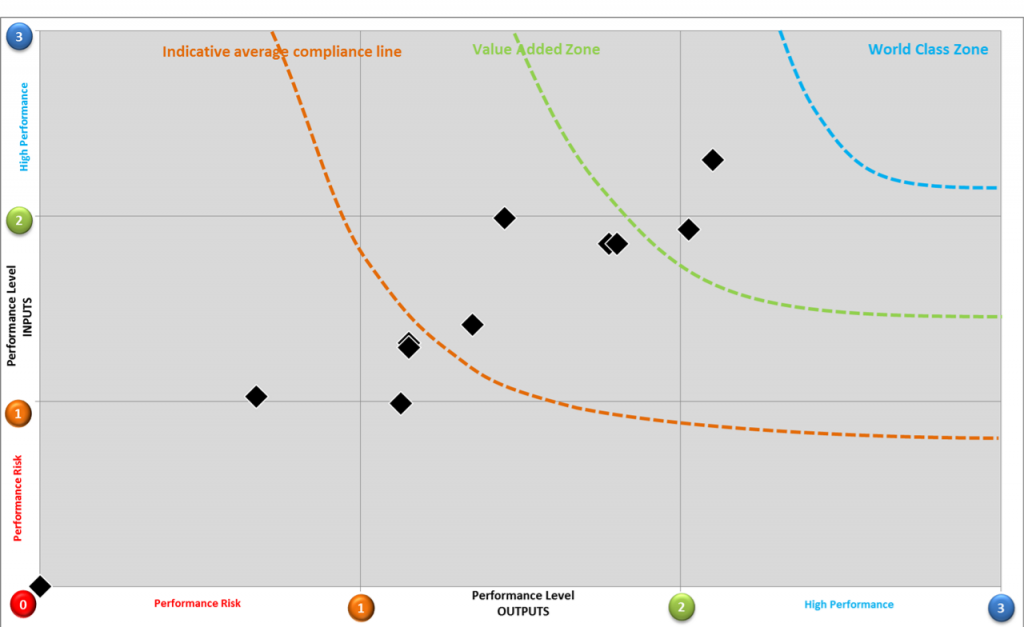

4. Performance benchmarking Once final scores across all contracts have been agreed, Crossrail maps each contractor’s absolute and relative performance on a chart. 5. Communication of results On completion, the scores and performance chart are circulated to senior managers within Crossrail and each Tier 1 contractor. 6. Performance improvement plans and intermediate review meetings After the conclusion of the assessment round, Tier 1 contractors are invited to develop a performance improvement plan. Crossrail discusses progress against these plans with each contractor at intermediate review meetings which take place approximately half-way between each six-monthly assurance assessment. Table 6 – Main stages of the Social Sustainability PAF assessment process

3.1 Maximising value from the assessment process

Although the main stages of the PAF assessment process have remained largely unchanged, Crossrail has made some adjustments to how the process has operated. As with the changes made to PAF contents, most of these adjustments took place in or after 2014, based on the first two years’ experience of operating the Social Sustainabiity PAF and participants’ reflections on how to maximise the value from the assessment process.

a) Allowing each Tier 1 contractor to define its own level of ambition for the PAF

Contractors have varied in their degree of enthusiasm for exceeding PAF basic compliance criteria, both generally and in relation to specific performance areas. Whilst peer comparisons and the sharing of good practice have encouraged some to move up the ratings, latterly Crossrail has sought to emphasise each contractor’s responsibility for its own performance. Accordingly, so long as it achieves compliance with the minimum contractual requirements, each Tier 1 contractor has been allowed to decide its level of ambition for itself.

b) Taking particular pains to ensure consistent and fair scoring across all contracts

Since 2014 even more attention than before has been paid to justifying scores by explicit references back to the relevant performance criteria, and undertaking a second, validation exercise before scores are finalised. This was felt to be essential for giving Tier 1 contractors greater confidence that they were being assessed on a level playing field.

c) Improving collaboration

Since 2014, Crossrail has taken various steps to improve collaboration within and between contracts. These have included:

• Reducing the number of attendees at review meetings (helped by the sharper focus of the PAF on skills and employment matters), and using these meetings primarily to address any non-compliance issues;

• Offering support outside the formal assessment process to help resolve non-compliances. Instead of dictating a resolution, Crossrail has encouraged contractors to develop their own approach, drawing wherever possible from good practice examples from other contractors;

• Establishing quarterly Social Sustainability Working Group meetings to provide Tier 1 contractors with a collective forum for sharing good practice across the project. The Working Group has also fostered the development of a handy network for contractor Social Sustainability leads representatives and generated healthy competition between contracts.

d) Recognising and rewarding outstanding performance

From 2015 onwards, success in Crossrail’s two annual award competitions (Apprentice Awards and Sustainability Awards) has been tied directly to Tier 1 contractors’ performance under the Social Sustainability PAF. These have offered contractor Social Sustainability leads and their organisations a further incentive to align Input and Output performance as closely as possible with PAF Value Added and World Class requirements.

Figure 5 – Laing O’Rourke C510 Liverpool Street Station: winners of Crossrail Apprentice Employer of the Year 2015

Figure 6 – Morgan Sindall C350 Pudding Mill Lane Portal: winners of Crossrail Social Sustainability Award 2015

4. PERFORMANCE OUTCOMES

Having described the contents of the Social Sustainability PAF and the assessment process, the next section reviews the degree to which these can be said to have had a positive impact on Tier 1 contractors’ performance during the period of the PAF’s operation, from 2013 to 2016. For these purposes, the two versions of the Social Sustainability PAF will be reviewed separately in turn.

4.1 PAF Version 1 Impact

During the early days of the project Crossrail’s two priority objectives were bedding in the performance assurance process itself and generating greater confidence that Tier 1 contractors were on track at least to achieve their minimum Output obligations under the Works Information Responsible Procurement provisions.

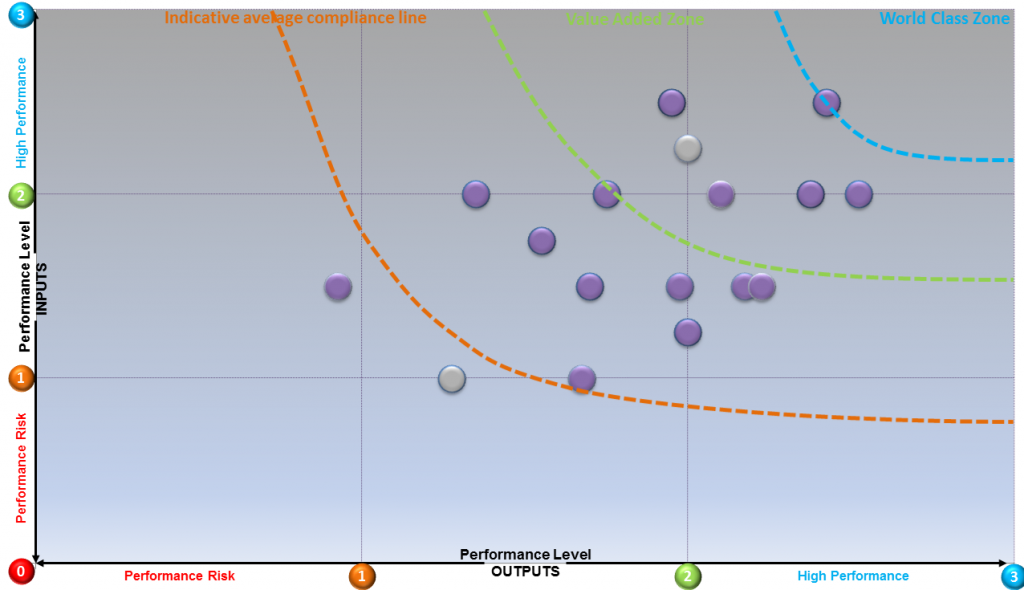

Judged against these two priorities, PAF Version 1 can be regarded to have achieved a considerable measure of success. In general terms, the PAF did manage to embed the process of performance management on the project. More specifically, it served to highlight individual Tier 1 contractors’ initial progress (or in some cases lack of progress) in fulfilling their contractual Output obligations. The resulting pressures to deliver – from both Crossrail and through comparisons with their peers – proved particularly helpful in incentivising Tier 1 contractors to fulfil, and in several cases exceed, their SLNT targets. This in turn gave Crossrail greater assurance that its own skills and employment commitments were likely to be met. By the time of the third and penultimate assessment under PAF Version 1, most contracts had made significant progress against the original PAF performance criteria and were achieving relatively high scores, as demonstrated in Figure 13 below.

Figure 7 – PAF Round 3 results

4.2 PAF Version 2 Impact

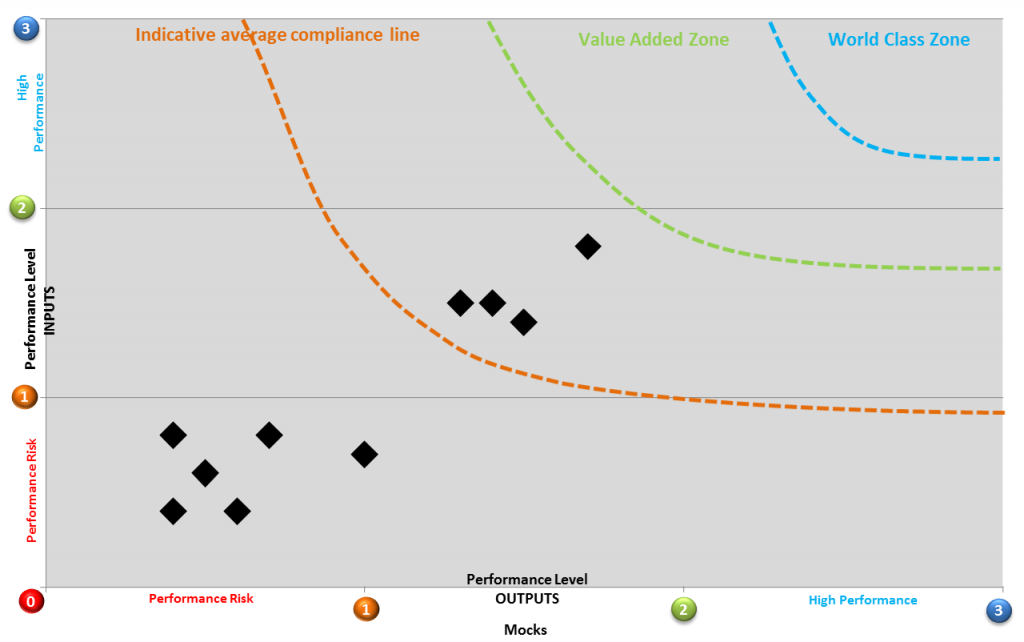

Inevitably, the very substantial changes made to the Social Sustainability PAF in 2014 caused a significant reconfiguration of scores across the project. The effects were particularly stark on those contracts where Output performance had previously been relatively good, but supporting Inputs (i.e., systems processes, policies and procedures) were poor or absent. The mock assessments carried out in autumn 2014 (illustrated in Figure 14 below) identified a clear gap between a minority of contracts where performance against the new criteria held up fairly well, and the majority where considerable additional work would now be required to claw back the position.

Figure 8 – Results of PAF Version 2 Mock assessment – Autumn 2014

As with PAF Version 1, successive assessments under PAF Version 2 have seen steady improvement in overall contractor performance: as illustrated in Figure 15. On each of the weakest contracts, Crossrail’s Social Sustainability team has worked hard to understand the specific obstacles underlying non-compliance with Works Information requirements. For the most part, Tier 1 contractors have been willing to cooperate in tackling these, although in a few cases it became necessary to seek an intervention from Crossrail middle or senior management in order to break an impasse.

Figure 9 – PAF Round 7 results

Whilst overall scores have improved, Figure 15 also confirms that performance has continued to vary across contracts. A few Tier 1 contractors have remained only superficially engaged, content to fulfil minimum Output requirements but little more. In other cases, PAF Version 2 has proved genuinely transformational, with several contractors introducing substantial improvements to their management processes in line with the amended PAF requirements. These improvements have in turn helped to inform the same contractors’ approaches in addressing similar client requirements on other projects, including the Thames Tideway Tunnel and High Speed 2.

5. LESSONS LEARNED AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This section analyses some of the key lessons learned from this experience, plus recommendations for other client organisations which might be considering implementing something similar.

5.1 Benefits of a PAF (or equivalent) process on a major project

At the outset it is important to re-emphasise that the PAF has not operated in a vacuum. A key principle underlying PAF development was that the starting point for assessing contractor performance (i.e., basic compliance levels) had to be rooted in the contract and Crossrail’s overarching strategic priorities. Without the 2010 Skills and Employment Strategy and the Works Information’s ‘Responsible Procurement’ provisions, any attempt to subsequently introduce Social Sustainability performance criteria and assessments would almost certainly have struggled to gain any momentum.

The principal contribution of the PAF has been that it gave Crossrail a strong, and at the same time flexible, mechanism for driving contractor performance towards achievement of its strategic priorities. Specific benefits have included:

• Providing an alternative incentive for contractor performance, to make up for the fact that Crossrail (as a one-project organisation) has no power to incentivise through promises of repeat work. The main elements of this alternative incentive have included the visibility generated by regular assessments, peer pressure (considerably enhanced by the use of charts portraying contracts’ relative position) and the sharing and celebration of good practice.

• Encouraging contractors to innovate above and beyond contractual requirements (and thereby partially overcoming constraints imposed by public procurement rules on what contractual clauses can and cannot require).

• Enabling Crossrail to make adjustments in particular areas over time. The development of PAF Version 2 half way through, for example, allowed Crossrail to incorporate lessons learned from implementation of PAF Version 1 and to modify its own priorities to reflect the changing nature of the project (viz. placing more emphasis on supply chain management to reflect the greater reliance on subcontractors during the stations and system-wide fit-out phase).

Recommendation 1:

As a preliminary step, client organisations need to establish clear strategic priorities in relation to Social Sustainability and embed these in contractual requirements so far as possible.

Once this has been done, there are considerable potential benefits in further supporting and supplementing these contractual requirements through development of a strong yet flexible performance assurance framework. These benefits include driving contractors’ delivery of the client’s strategic priorities, encouraging performance above and beyond mere contractual compliance, and allowing adjustments to be made in particular areas to reflect previous lessons learned or changing circumstances.

Figure 10 – Tideway is implementing the main elements of the PAF process5.2 The need to allow for some flexibility in applying performance criteria

The fundamental purpose of PAF assessments (or any equivalent process) is not to serve as a mere auditing tool, but rather actively to support contractor delivery of the client’s strategic objectives. Necessarily, this has involved Crossrail adapting and evolving its expectations over time and to reflect the diversity of contractors’ circumstances.

Examples of this need to take a flexible and proportionate approach include the following.5.2.1 Updating and improving Responsible Procurement Plans

Under the terms of Crossrail’s contract, each Tier1 contractor was required to submit a draft version of its Responsible Procurement Plan at the procurement stage, and a final version within four weeks of contract award. With hindsight, this timeframe now seems unrealistic and even counterproductive. In practice, contractors’ Social Sustainability delivery teams were not in place, either at procurement (tender responses generally being drafted by bid teams not involved in delivery), or immediately post award. As a result, many Responsible Procurement Plans were little more than a copy of the contract terms, containing little if any explanation of the systems, policies, procedures and resources that needed to be in place if Crossrail’s Social Sustainability objectives were to be met.

As has already been explained, Crossrail eventually tackled this problem by placing a greater emphasis in PAF Version 2 on Input measures of performance. This rebalancing of the PAF prompted most contractors to amend and update their Responsible Procurement Plans, assisted by Crossrail’s Social Sustainability team and good practice examples from elsewhere. By encouraging them to clarify and upgrade their systems, policies, procedures and resources, these revisions also helped many contractors eventually improve their delivery of the Output measures of performance.

Future clients should benefit from at least some contractors now having a better idea of the processes required to deliver Social Sustainability objectives (not least because of lessons learned from the Crossrail project). Nevertheless, we believe that there will still be merit in treating contractor Responsible Procurement Plans (or their equivalent) as living documents, to be updated and amended from time to time in order to reflect lessons learned and/or changed circumstances.5.2.2 Taking due account of the size, nature and delivery phase of individual contracts

During each round of PAF assessments, contracts have differed from one other in various ways, including their relative size/ value, the nature of the activities being undertaken (i.e., labour or capital intensive), and the phase of delivery (i.e., extent of reliance on subcontractors rather than self-delivery by the Tier 1 organisation). Initially there were understandable concerns expressed by some contractors that Crossrail was applying the same expectations to all contracts, and that consequently smaller and less labour-intensive contracts could be penalised because of their more limited opportunities to exceed minimum contractual requirements, particularly in relation to the delivery of SLNT targets.

Especially after the introduction of PAF Version 2, Crossrail has sought to assuage such concerns by emphasising its expectation that each contract should look to maximise the available opportunities through ongoing implementation of effective processes, in line with its Responsible Procurement Plan. As a consequence, expectations during successive assessment rounds were tailored to the size, nature and delivery phase of each contract. In particular, Crossrail based its assessment of Output performance mainly on activities and achievements during the preceding six-month period, rather than on any longer-term historical performance.

5.2.3 Keeping evidential requirements relevant and proportionate

Crossrail was keen to avoid PAF assessments being perceived as unnecessarily burdensome or bureaucratic. Accordingly, Crossrail adopted a degree of flexibility in relation to the evidence required to demonstrate performance. Whilst PAF Version 2 listed examples of acceptable evidence, Tier 1 contractors had the option of submitting alternative evidence provided this was suitable and relevant.

Likewise, contractors were not required to submit evidence already reviewed in previous assessments. This was particularly pertinent when it came to evidence of Input measures of performance, which were essentially the systems, processes, procedures and resources in place to deliver each area of the PAF. In the absence of any significant changes, there was no requirement to resubmit such evidence. By contrast (and as we have seen), Crossrail did expect contractors to submit evidence of Outputs every six months, in order to demonstrate their ongoing implementation of the Inputs.

Recommendation 2:

In implementing a performance assurance process, client organisations should allow for a degree of flexibility. This is to ensure that the process is perceived as supporting the practical delivery of strategic objectives as opposed to a bureaucratic or box-ticking exercise. Any framework should permit (and preferably encourage) contractors to update and improve their implementation processes over time. It should also be designed and/or applied so that contracts are assessed fairly, regardless of size, nature and delivery phase. Evidential requirements should also be relevant and proportionate.

Figure 11 – Knorr-Bremse platform edge screen contract

5.3 Benefits of combining a range of mutually reinforcing mechanisms (both contractual and non-contractual) in order to drive contractor performance

Before the development of the PAF in 2012-13, the Responsible Procurement provisions of the contract did not always deliver constructive exchanges between Crossrail and its contractors. Contractual quarterly meetings typically focused on testing the accuracy and completeness of each contractor’s (contractually-mandated) quarterly report and progress in delivering easily quantified contractual SLNT targets. Neither side devoted as much attention to other aspects of performance or to consideration of the underlying enablers or obstacles to improving performance.

Introduction of the non-contractual PAF process in early 2013 started to broaden the scope of these quarterly discussions. Replacement of PAF Version 1 with Version 2 in 2014-15 took this a stage further. At the same time, as we have seen, Crossrail introduced a range of additional, non-contractual mechanisms designed to reinforce Works Information requirements and the PAF, including a Social Sustainability Working Group and award schemes linked directly to performance against PAF criteria. These various measures have all paid dividends, in driving contractor performance and improving collaboration both between Crossrail and its contractors and among contractors themselves.

Recommendation 3:

Each client organisation should work to put in place a coherent system of mutually reinforcing contractual and non-contractual mechanisms to drive contractor performance in line with its overarching strategic priorities. In particular, clients should look to facilitate sharing of good practice and innovation, as well as healthy competition and recognition and reward.5.4 Maintaining positive client-contractor relationships

Whilst it is possible to characterise the PAF process as partly coercive (viz. through the regular visibility given to any instances of poor performance), ultimately PAF assessments would have proved unworkable without the acceptance and collaboration of Tier 1 contractors. As outlined above, Crossrail’s Social Sustainability team sought at various stages, and in different ways, to secure contractor buy-in – for example:

• By involving contractors in the design and subsequent redesign of PAF contents;

• In minimising the staff time and bureaucracy taken up by the assessment process;

• By providing mock assessments ahead of introduction of PAF Version 2, and offering direct support to contracts struggling to resolve non-compliances;

• By taking due account of differences between contracts and the implications such differences might have on what particular contracts could reasonably be expected to achieve; and,

• In promoting the sharing and celebration of good practice through the establishment of a Social Sustainability Working Group and award schemes linked to PAF performance criteria.Future clients may decide to establish direct commercial incentives and/or penalties linked to contractors’ performance or non-performance of their Social Sustainability obligations. Although such measures should at least help capture contractors’ interest, even here clients will probably still need to work on building and maintaining positive relationships with their contractors – for example:

• To motivate contractors to achieve more than the minimum necessary to secure the incentive and/or avoid the penalty;

• To maximise contractors’ willingness to be flexible in the event of a change in circumstances or adjustment in priorities; and,

• To obtain contractors’ co-operation in lower-priority areas, which might not be included in the incentive or penalty.Recommendation 4:

Regardless of whether or not direct commercial incentives or penalties are attached to Social Sustainability obligations in future, clients should continue to devote considerable attention to building and maintaining positive relationships with contractors, in order to maximise collaboration and promote discretionary performance behaviours.5.5 Securing internal organisational support at all relevant levels

On Crossrail, Social Sustainability benefited from a high degree of awareness and commitment at a senior level, up to and including the Chairman. This in turn reflected the importance both Crossrail and external stakeholders attached to the commitments made in the Skills and Employment Strategy , including job opportunities for local people, apprenticeships, equality and diversity, and the London Living Wage.

Executive responsibility for ensuring Crossrail’s Social Sustainability objectives lay with the Talent and Resources Director, who reported regularly on progress to the Executive Committee and the Board. Crossrail’s Board established a dedicated committee overseeing implementation of sustainability as a whole (i.e., covering economic and environmental matters, as well as Social Sustainability), later transferring this remit to a sub-committee of the Executive Committee, chaired by the Chief Executive.

This focus at a senior level raised awareness of Social Sustainability and individual contractors’ PAF performance elsewhere in the organisation, and meant that on occasions Crossrail’s Social Sustainability team was able to call upon Executive support to overcome persistent performance problems on particular contracts.

Interest among Crossrail’s contract-based staff (i.e. project managers, project business managers and contract administrators) should have been more engaged in the early days of the project to persuade this group to take ownership of the Social Sustainability agenda on their contracts. At times, as well, the Social Sustainability team (who were head-office based) were possibly too quick to escalate concerns to the Executive, bypassing contract-based staff.

When rolling out PAF Version 2 during 2014-15, the Social Sustainability team consciously set out to build closer relationships with Crossrail contract teams. As well as strengthening support for Social Sustainability and the PAF process among this crucial group, closer engagement helped the Social Sustainability team understand better the formal mechanisms used by the contract teams to manage relationships with their Tier 1 contractors. After the Tier 1 contractor’s organisational effectiveness and commitment, the strength of support from Crossrail’s own contract team has proved the next most powerful predictor of contracts’ ultimate PAF assessment rating.

Recommendation 5:

Client organisations should ensure that there is strong support at all relevant levels of the organisation for Social Sustainability priorities. Results of performance assurance assessments should be made visible to all internal stakeholders. From the outset there should be a concerted effort to win the active support of contract-level delivery teams, who should also be allocated clear responsibilities to support the ongoing implementation of a performance assurance framework (or equivalent) at contract level. Ideally, a client organisation should also incorporate Social Sustainability priorities into relevant delivery team members’ personal performance management objectives. By the same token, the client’s Social Sustainability specialists should take care to build and maintain strong relationships with contract delivery teams, and respect (and when appropriate use) the formal contractual mechanisms with which the latter administer the relationship with Tier 1 contractors.Figure 12 – BFK C435 Farringdon Station

-

Document Links

-

Authors

Anne-Sophie Blin MSc

Anne-Sophie Blin was the Lead Social Sustainability Officer at Crossrail from 2013 to end of 2016. In this role, she oversaw the implementation of the Crossrail Social Sustainability strategy, working with contractors to ensure they fulfilled their contractual obligations in relation to job creation, skills developments, promoting equality and diversity, and enforcing the London Living Wage. Before joining Crossrail in 2013, Anne-Sophie advised international property companies on developing and implementing strategies covering environmental and economic as well as social sustainability. She holds an MSc in Urbanisation and Development from the London School of Economics and a Master’s degree in International Relations from Sciences Po, Paris.

Andrew Eldred MA, MSc - Crossrail Ltd

Andrew Eldred was Head of Employee Relations at Crossrail until early 2017. His responsibilities included trade union engagement, oversight of contractors’ management of site employment relations, and delivery of apprenticeships and other skills and employment commitments. Before joining the Crossrail programme, Andrew held several senior employment relations roles in construction, including three-and-a-half years as the ODA Delivery Partner’s Industrial Relations Manager on the London 2012 Olympic Park construction programme. He holds an MA in Modern History from the University of Oxford and an MSc in Human Resource Management from Birkbeck College, London.