Apprenticeships

Document

type: Case Study

Author:

Anne-Sophie Blin MSc, Andrew Eldred MA, MSc

Publication

Date: 27/09/2016

-

Abstract

This case study outlines the apprenticeship initiatives adopted by Crossrail as part of its Skills and Employment Strategy, including imposition of contractually-binding apprenticeship targets. It describes some of the main characteristics of contractors’ apprenticeship arrangements and explains how Crossrail’s priorities broadened half-way through the project to encompass extra qualitative aspects of contractors’ delivery of apprenticeships, and improved sharing and recognition of good practice. The report then attempts a balanced assessment of those areas where contractor performance seems to have improved over the course of the project, and those areas (not mutually exclusive) where more work remains to be done. The report ends with lessons learned and recommendations for the future.

This report would be of interest to HR directors, skills and employment specialists and social sustainability specialists.

-

Read the full document

Context

The following report describes Crossrail’s implementation of a variety of apprenticeship initiatives, including the delivery of apprenticeships by Tier 1 contractors and their supply chains. Before turning to consider this, the paper first examines the broader context for apprenticeship training in construction, including significant structural obstacles to industry investment in workforce skills.

What is an Apprenticeship?

An apprenticeship may be defined as a job with training. Conventionally, apprentices will have a contact of apprenticeship or employment and receive an hourly wage. Their training should involve a mixture of college-based learning and real-life experience gained whilst working. In the UK and elsewhere, apprenticeships are widely perceived as an effective means of addressing levels of youth unemployment.

The Decline in Construction Apprenticeships

Despite a partial recovery in recent years, the number of construction apprenticeships in the UK remains well below historic levels.[1] According to one recent account, there were only 18,000 construction apprentice starts in the UK during 2014/15, with drop-out rates close to 50%.[2] A lack of effective quality also means that not all opportunities badged as ‘apprenticeships’ necessarily provide individuals with measurable learning outcomes, such as knowledge, skills and competence. [3]

At first glance, this decline in construction apprenticeships might appear surprising. The industry continues to generate a high level of demand for intermediate and advanced level skills – both in traditional trades and new technologies.[4] Government and industry leaders regularly proclaim their desire to attract more young people into the sector.[5] Almost uniquely, construction retains a training board (the CITB) and a statutory training levy.

Running counter to all this, however, are significant structural obstacles to any general or sustained investment in workforce skills. Among these is the widespread fragmentation of industry employment, including a heavy reliance on subcontracting and high levels of self employment, much of it false.[6] High levels of subcontracting, particularly to SMEs, mean that there are significant transaction costs associated with training provision and little incentive for employers to take apprentices on.[7] Incentives to train are further undermined by a construction market dominated by competition on price rather than innovation,[8] declines in the influence of trade unions and collective wage setting,[9] and an ever-greater dependence on immigration as a source of labour.[10] Those construction employers who do invest in training are faced with the problem of ‘free-riders’ (i.e., competitors who avoid paying for training themselves, instead poaching qualified workers from other firms). In these circumstances, it is hardly surprising if the UK is sometimes characterised as trapped within a ‘low-skill equilibrium’, [11] contributing to comparatively poor levels of construction productivity, quality and innovation, in comparison to other countries.[12]

Figure 1 – Despite a high demand for skills and a statutory training levy, most UK construction employers are still failing to recruit and train apprentices.

Construction Clients and Apprenticeships

Recent years have seen a growing interest in client organisations’ potential role in helping to revive construction apprenticeship training. This contrasts with earlier trends (from the 1970’s onwards), when many clients pulled back from regulating construction supply chain employment arrangements through ‘social clauses’ or other means. This ‘hands-off’ approach was further reinforced by UK and EU legislation restricting the consideration of ‘non-economic’ factors in public procurement. [13]

By contrast, local authorities now routinely impose ‘Section 106’ jobs and skills requirements on developers as a condition of planning consent. On a larger scale, the Olympic Delivery Authority started in 2008 with an apprenticeship target of 100, subsequently increased this to 350, and eventually reported over 400 apprentices as having spent 30 days or more working on the Olympic Park or Athletes’ Village.[14] Crossrail’s apprenticeship programme, as will be seen below, has sought to be even more ambitious than this. In addition, the project has been fortunate to coincide with, and contribute to, wider policy developments aimed at transforming support for apprenticeships from a minority interest into a mainstream client requirement.

Before examining Crossrail’s experiences in more detail, however, it is worth recalling the structural obstacles cited above. To a large degree, every client – regardless of the size of its project or the strength of its contractual requirements – has little option but to work with, rather than against, the grain of current construction supply chain arrangements in order to meet its apprenticeship objectives. That is not to say that clients lack power to shape and change contractors’ practices. However, in the absence of greater consistency between clients and/or a deeper construction industry reform (both of which are touched upon in the Recommendations section), the most that a single client can probably hope to achieve is partial and incremental improvement.

Having established the context, the next section describes the main Crossrail apprenticeship initiatives themselves.

Apprenticeship Initiatives on the Crossrail Project

Early on, Crossrail formulated a Skills and Employment Strategy, in which it committed to contribute to developing a skilled workforce for employment on this and future infrastructure projects. Apprenticeships have been at the core of this Strategy.

TUCA Apprenticeships

Since 2011, Crossrail’s Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy (TUCA), in Ilford, has provided apprenticeship courses in Tunnelling Operations, Sprayed Concrete Lining and Plant Mechanics. TUCA has also established an Industrial Partnership in Tunnelling and Underground Construction, and an associated Industry Delivery Partnership, charged with designing new training programmes in response to (and anticipation of) technological advances and industry needs. Specific outputs have included:

- Development of a Materials Testing apprenticeship, which it is hoped will evolve into a new-style Trailblazer Standard;

- Development of a Tunnelling Operations Trailblazer apprenticeship standard;

- Initial plans to develop new apprenticeship standards at technician level and in Sprayed Concrete Lining.

TUCA is explained in more detail in a separate learning legacy paper.

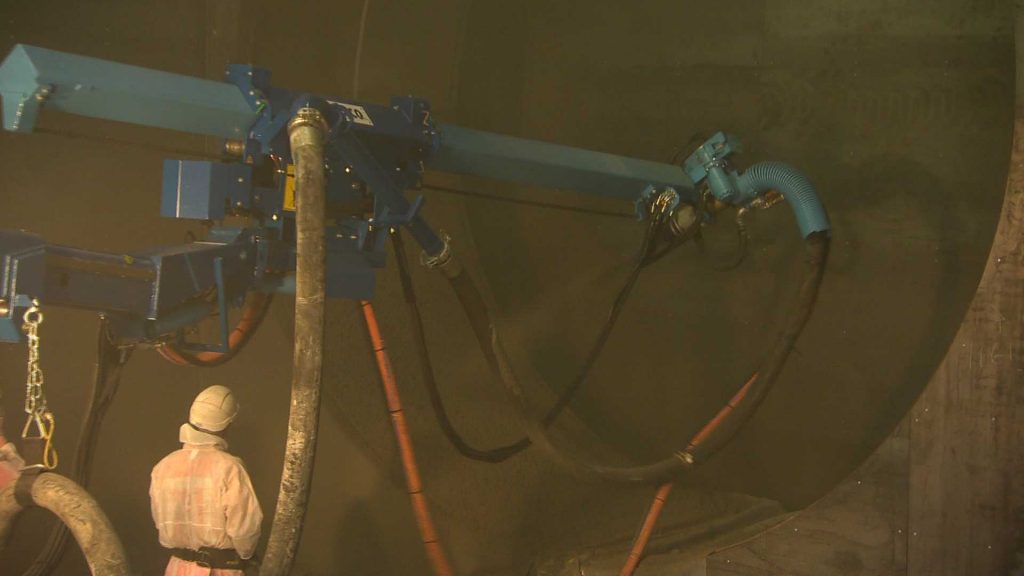

Figure 2 – Crossrail’s Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy (TUCA) has provided apprenticeships in a variety of disciplines, including sprayed-concrete tunnelling.

Crossrail in-house Apprenticeship Scheme

As a temporary and comparatively small organisation, employing mainly professional and support staff, Crossrail’s scope to take on apprentices and offer them sustained employment after completion has necessarily been fairly limited. Nevertheless, in view of the priority assigned to apprenticeships in the Skills and Employment Strategy, Crossrail has endeavoured to lead by example. The Talent and Resources directorate has liaised closely with Directors and functional leads to identify apprenticeship opportunities, and is expected to achieve just under 40 apprenticeship completions by the end of the project. All Crossrail in-house apprentices have been engaged on an advanced (NVQ 3) business administration framework, attending classes on day release at Lambeth College.

Contractor Targets and Safeguarding Quality

In 2009, Crossrail set a target of creating 400 apprenticeships over the lifetime of the project. As a precondition of contracting, Crossrail has worked with its contractors to establish numerical Strategic Labour Needs and Training (SLNT) targets for each contract. These are based on the value of each contract and require the delivery of one SLNT ‘output’ for every £3 million of contract value. A minimum of half of all ‘outputs’ calculated using this metric must be either local job starts or apprenticeships.

In addition to maximising the number of apprenticeships on the project, Crossrail has sought to protect the quality of these apprenticeships by imposing certain minimum safeguards. For example, the decision was taken to express Tier 1 contractors’ numerical SLNT targets as ‘outputs’, with associated minimum standards, rather than ‘heads’. This has arguably helped minimise any incentive to meet these targets by hiring large numbers of individuals on low-quality frameworks of short duration.

To count as one apprenticeship ‘output’ for SLNT target purposes, an individual must be pursuing a structured programme of training which leads to the completion of a full apprenticeship and is recognised by a sector skills council or standard setting body. The apprentice must also have worked on the project for at least 16 weeks in any one year, although in practice most stay much longer.

So far as reasonably practicable, apprentices should also be regular employees of a Tier 1 contractor, trade or labour-only subcontractor, or employment business. This is instead of being supplied on a temporary basis by an intermediary, such as an Apprenticeship Training Agency. Contractors must also demonstrate a process for developing and monitoring training plans for apprentices.

Figure 3 – Crossrail’s contracts include provisions designed to safeguard apprenticeship quality, as well as numerical targets.

Monitoring and Performance Management

As well as writing apprenticeship targets and minimum standards into contracts, Crossrail has implemented assurance processes actively to manage Tier 1 contractors’ performance. These have included:

- Quarterly progress reports, in which contractors are asked to provide details such as:

- Apprentice’s gender and date of birth;

- Title of the apprenticeship framework;

- Identity of employer;

- Locations of the apprentice’s home and college; and

- Apprentice’s unique college registration number (to avoid counting the same individual more than once).

- Twice-yearly performance assessments, using Crossrail’s Social Sustainability Performance Assurance Framework (PAF).

The Performance Assurance Framework is detailed in a separate learning legacy paper.

The rest of this report focuses principally on Crossrail’s experience in overseeing how Tier 1 contractors and (to a lesser extent) their supply chains have gone about delivering apprenticeships on the project. This account is divided into three parts, as follows:

- An outline of some of the main features of contractor apprenticeship arrangements;

- An explanation of why, in 2014, Crossrail and Tier 1 contractors agreed to start taking account of a broader range of performance indicators in relation to the delivery of apprenticeships;

- A description of some of the ways in which, latterly, Crossrail has attempted to disseminate good practice and further improve contractor performance.

Common Features of Contractor Apprenticeships

Apart from the numerical targets and minimum qualitative safeguards described above, Crossrail initially left it largely to Tier 1 contractors to decide for themselves how to go about delivering apprenticeships on the project. Questions such as which apprenticeship frameworks to use, the level of frameworks, how much to pay apprentices and the degree to which trade contractors and labour suppliers should become involved in delivering apprenticeships have therefore largely been left to Tier 1 contractors’ own discretion. Until 2014, Crossrail’s reporting and performance assurance processes also focussed predominantly on ensuring that Tier 1 contractors were on track to fulfil their numerical targets, rather than broader performance matters.

The following overview provides a mainly positive account of common features of contractors’ apprenticeship arrangements, as revealed through Crossrail’s reporting and performance assurance processes.

Tier 1 Corporate Schemes

In all but one case, each Tier 1 contractor (or at least one of the partners in a joint venture) has had a corporate apprenticeship scheme in place before becoming involved with the Crossrail project. These schemes vary in size and ambition. Whereas some play a central role in their firm’s resourcing strategy, others appear to operate principally as a means of fulfilling client apprenticeship requirements. Most (72%) of the apprentices on Crossrail so far have been employed directly by a Tier 1 contractor through one of these corporate schemes, rather than by a trade subcontractor or labour supplier.

Figure 4 – Apprentice Shane McHugh working on Hochtief-Murphy joint venture’s C310 Thames Tunnel contract.

Choice of Discipline

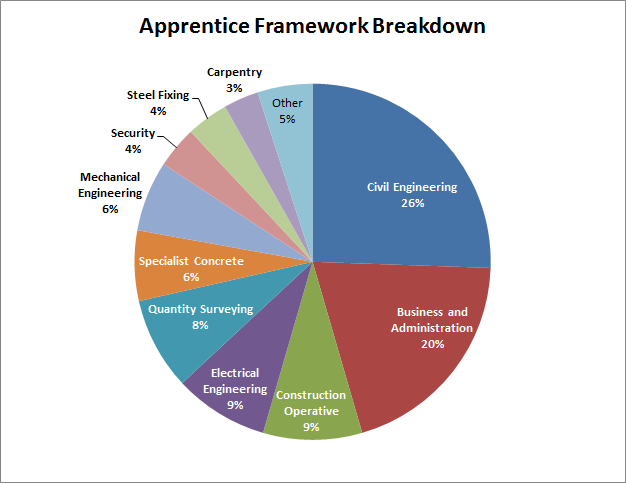

In nearly all cases, Tier 1 contractors’ use of their own corporate schemes has meant that construction, engineering and related disciplines have tended to predominate – as illustrated by the breakdown in Chart 1 below. Given the nature of the project, Crossrail has welcomed this balance. The main exception has been one Tier 1 contractor which did not have an existing corporate scheme, and has relied instead on employing a relatively high proportion of apprentices on a generic (business administration) framework to fulfil its numerical target.

Chart 1 – Breakdown of apprentices on Crossrail by framework (up to February 2016). So far, around 70% of apprentices of the project have been employed on construction or related frameworks.

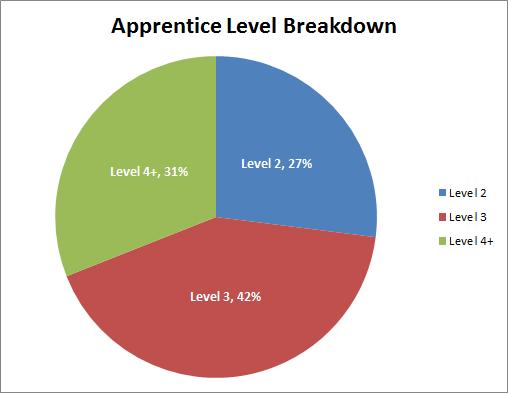

Level of Apprenticeships

Three levels of apprenticeships are available in the UK:

- Intermediate level apprenticeships (NVQ level 2)

- Advanced level apprenticeships (NVQ level 3)

- Higher apprenticeships (NVQ level 4 and above).

Just as with the choice of discipline, Crossrail has never sought to restrict contractors’ selection of framework levels (i.e. intermediate, advanced or higher). This recognises the diversity of skill levels during different phases of the construction process, particularly amongst subcontractors.

In practice, the balance between different levels has tended to reflect each Tier 1 contractor’s delivery model and/or the extent of trade contractor and labour supplier involvement in delivering apprenticeships. For example, Tier 1 contractors who generally confine their direct activities to managing a supply chain have tended to recruit predominantly advanced and higher level apprentices. By contrast, Tier 1 contractors who still employ significant numbers of construction operatives directly and/or who have actively encouraged trade contractors and labour suppliers to employ apprentices usually report a more mixed range of levels.

Figure 6 – Laing O’Rourke’s C502 Liverpool Street Station contract: winners of the Crossrail Apprentice Employer of the Year Award 2015. The judges’ award citation highlighted, in particular, the range of apprenticeships the firm provides, including intermediate, advanced and higher levels.

Intermediate apprenticeships have predominated on just two contracts. Whilst superficially similar, these cases have in fact differed quite significantly, both with respect to the reasons for adopting lower-level frameworks, and the amount of further training and development apprentices have received after completion.

The first case once again involved the Tier 1 contractor with no apprenticeship programme before the Crossrail project. In this instance, nearly all its business administration apprenticeships were at intermediate level, with progression to higher levels in only a few cases.

In the second case, Morgan Sindall made a conscious decision on its C350 Pudding Mill Lane Portal contract to focus on entry-level opportunities, despite having a well-regarded corporate apprenticeship scheme of its own. The main driver for this decision was to encourage and support labour suppliers – not traditionally associated with offering apprenticeships – to provide an intermediate construction operations framework to local young people from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. On completion, Morgan Sindall has also ensured that all former apprentices have remained in employment and received further training, enabling them to acquire extra ‘tickets’ to operate different types of construction plant.

Looking at the project as a whole, Chart 2 below confirms that the balance between different levels has been reasonably even so far. It seems likely that the share of advanced and higher level frameworks will grow over the next two years – reflecting the generally higher skill requirements of building, mechanical, electrical and railway systems work, in comparison with civil engineering.

Chart 2 – Breakdown of apprentices on Crossrail by NVQ level (up to February 2016).

Chart 2 – Breakdown of apprentices on Crossrail by NVQ level (up to February 2016).Rates of Pay

Whilst Crossrail has imposed a general policy of London Living Wage compliance on the project, it has not insisted on this rate for apprentices. This was a pragmatic decision, based on the need to avoid causing undue disruption to existing pay structures, including differentials. It has also provided some advantages for apprentices themselves – for example, facilitating transfers between Crossrail and non-Crossrail contracts. This approach is also in line with Living Wage Foundation guidance that apprentices need not receive the full rate.

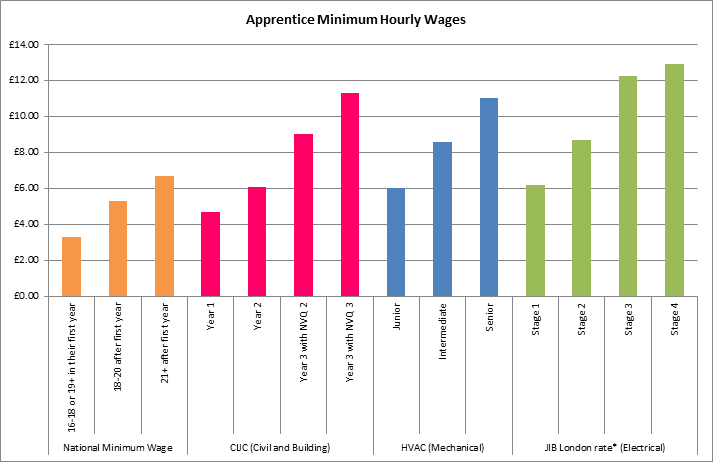

Instead, employers have been encouraged to pay at least in line with industry benchmark wage rates for apprentices, such as those set out in the Construction Industry Joint Council (CIJC) Working Rule Agreement. These rates exceed the National Minimum Wage apprentice rates by some margin. Most Tier 1 contractors are members of the Build UK trade association (signatory to the CIJC), and therefore tend to operate rates of pay for their own construction apprentices at or above CIJC rates any way. This requirement is not necessarily passed down to trade subcontractors or labour suppliers, however.

Trade associations for other speciality areas, such as mechanical and electrical contracting, also operate apprentice rates, negotiated as part of their own National Working Rule Agreements (i.e., the HVAC for mechanical and the JIB for electrical). These rates tend to be higher than those in the CIJC.

Chart 3 – Comparison of minimum apprentice rates under the National Minimum Wage and various construction industry National Working Rule Agreements (as at February 2016). Crossrail has encouraged contractors and their supply chains to pay apprentices at least the applicable Agreement rate.

Cases where Crossrail has become aware of apprentices receiving only the National Minimum Wage apprentice rate, or a little bit more, have been quite rare. For example, Servest – a security contractor active on many contracts and which has so far recruited and trained 19 apprentices on the project – pays its apprentices well above the National Minimum rate. Tier 1 contractors’ difficulties in obtaining apprentice pay information from other subcontractors, however, could mean that low pay is more common than it has been possible to establish so far.

Promoting Good Practice and Improvement

Over time, Crossrail’s understanding of contractors’ approaches to the delivery of apprenticeships has improved thanks to the quarterly reporting and PAF processes. These have revealed significant differences of approach between contractors, both in relation to their management processes (e.g., recruitment, mentoring, supply chain engagement), and the outcomes achieved (e.g., completion rates, sustainable employment, diversity). By 2014 this led Crossrail to review the relevant literature, in order to identify a broader range of performance indicators for delivery of apprenticeships. [15] [15] [16] [18] Tier 1 contractors were then consulted for their own preferences and insights.

This exercise confirmed that there was scope for Crossrail to do more to highlight good practice in delivery of apprenticeships and, in particular, to encourage Tier 1 contractors to start making improvements in those areas where industry performance has traditionally been weak.Revising the Social Sustainability PAF

As a first step, and in consultation with Tier 1 contractors, Crossrail made revisions to the Social Sustainability PAF apprenticeship provisions during the second half of 2014. This included incorporating the following as new performance criteria exceeding basic contractual compliance:

- Operating a high-quality corporate apprenticeship scheme beyond the Crossrail project;

- Providing a high proportion of construction, engineering and related frameworks, relative to generic frameworks such as business administration;

- Maintaining an appropriate balance between different apprenticeship levels (i.e., intermediate, advanced and higher);

- Paying in line with industry benchmark wage rates, or better;

- Considering diversity in the recruitment and selection of apprentices;

- Ensuring high completion rates, and providing sustainable employment on completion;

- Engaging trade contractors and labour suppliers, in order to improve the number and quality of apprenticeship schemes operated by supply-chain firms.

Highlighting and Rewarding Good Practice

To complement these and other revisions to the Social Sustainability PAF, Crossrail started to convene regular joint working group meetings in 2015 to help disseminate good practice. Contractors rated especially highly for the quality of their apprenticeship delivery have been invited to share the distinctive features of their approach, followed by a more general discussion in which contractors as a group have been able to exchange queries, problems and insights with their peers. Examples are given later of some of the positive outcomes that have resulted from these exchanges.

As well as dissemination, Crossrail also sought to recognise and reward good practice through the annual Crossrail Apprenticeship Awards. Since 2015, Tier 1 contractors’ relative performance against the revised PAF apprenticeship criteria has determined which contracts have been short-listed for the Apprenticeship Employer Award. For 2016, an additional Supply Chain Apprenticeship Employer Award was introduced. The purpose of this new award was to encourage greater supply chain involvement by highlighting the achievements of those trade contractors and labour suppliers who are already delivering apprenticeships on the project to a high standard.Figure 9 – Martin Scott of Kilnbridge collects his firm’s award as 2016 Crossrail Supply Chain Apprenticeship Employer of the Year. So far, Kilnbridge have employed 14 apprentices on the project.

Results to Date

At the time of writing (July 2016), with another two years to go before completion, Crossrail and its contractors have managed to recruit and train almost 600 apprentices, well above the original 400 target. In addition, three PAF assessments have been completed to date using the revised apprenticeship criteria. This has resulted in marked changes in some contracts’ absolute and relative performance ratings under the PAF, which Crossrail believes more accurately reflects differences in the quality of contractors’ delivery of apprenticeships on the project.

In terms of measurable improvements in performance, however, progress so far remains mixed. With the benefit of hindsight, greater progress would probably have been achieved if some or all of the additional performance indicators introduced in 2014 had been in place from the start, and preferably underpinned by specific contractual requirements. The following accounts may prove helpful for other clients wishing to benchmark their own experience and/or considering ways of improving contractor performance on future projects.

Improving Diversity

As part of its wider Skills and Employment Strategy, Crossrail has sought to maximise job and development opportunities for local people and to improve the construction industry’s generally poor performance with regard to diversity. By incorporating a specific reference to diversity in the recruitment and selection of apprenticeships, it was hoped that the revised PAF would help reinforce these efforts.

Morgan Sindall’s initiative to recruit local young people into entry-level roles (see above) has been widely promoted to other Tier 1 contractors as good practice, including recognition of the leading role played by the contract’s Construction Manager at the 2015 Crossrail Apprenticeship Awards.

Figure 10 – Colin Edwards, Morgan Sindall Construction Manager and winner of the 2015 Crossrail Apprentice Advocate award for his mentoring of apprentices on the C350 Pudding Mill Lane Portal contract.

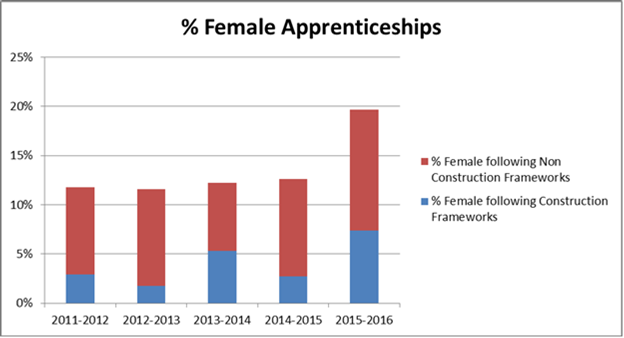

Crossrail has also been active in highlighting female role models from all levels on the project, and the partnership with Women into Construction has so far helped 25 women into jobs or apprenticeships, either with Crossrail or one of its Tier 1 contractors. Encouragingly, Chart 4 below confirms a recent upturn in the number of female apprentices as a share of the total new apprentice intake: 27% of the 2015-16 intake was female, more than double the 13% figure the previous year. The proportion of female apprentices on construction and related frameworks has also increased.

Chart 4 – Female apprentices as a proportion of the total new apprentice intake on Crossrail for each year (2011-12 to 2015-16). The chart also shows the breakdown between women following construction and non-construction apprenticeship frameworks.

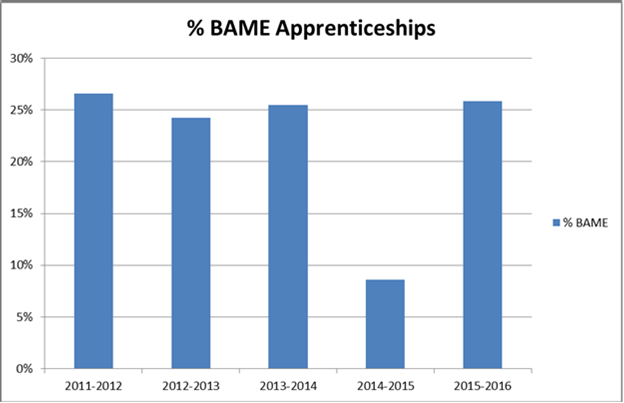

In 2015-16, 32% of the new apprentice intake across the project came from a Black Asian or Minority Ethnic (BAME) background. This too represents an improvement on earlier years, but – as with the gender balance – Crossrail recognises that there is still considerable room for improvement.

Chart 5 – BAME apprentices as proportion of the total new apprentice intake on Crossrail for each year (2011-12 to 2015-16).

Maximising Completion Rates

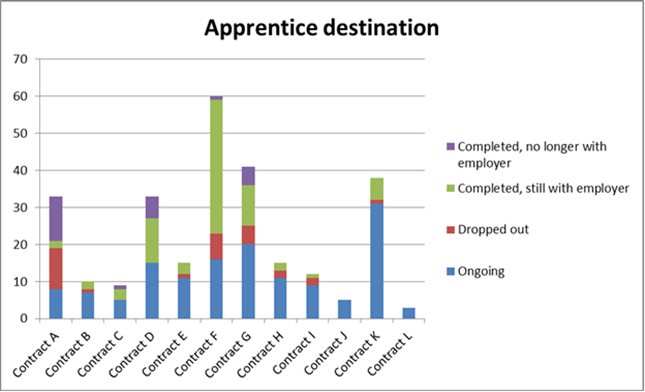

Most Tier 1 contractors with established corporate schemes have consistently reported high or very high completion rates – as displayed in Chart 5 below. Once this information started to be collected in 2014, however, high drop-out rates on two contracts gave some cause for concern. One of these involved the Tier 1 contractor which did not have an apprenticeship scheme in place before the Crossrail project (‘Contract A’ in the chart): here, 28% of apprentices had dropped out before completion. The other – not featured in the chart – involved a new joint venture responsible for one of the earliest large contracts. This contract struggled to balance delivery of numerical targets and quality, at one point recording a drop-out rate of 43%.

Chart 6 – Breakdown of apprentices on Crossrail by contract and destination (as at February 2016).

The PAF assessment process and discussions in working group meetings have helped to raise awareness of particular practices which appear to have contributed to very high completion rates on some contracts. Unsurprisingly, a thorough recruitment process has been highlighted as key to success. Some of the best performing contractors in this area – for example, the Balfour Beatty Bemo Morgan Sindall Vinci (BBMV) joint venture at its C510 Whitechapel and Liverpool Street Tunnels contract – offer work placements as a way of testing individuals’ motivation and suitability for an apprenticeship.

Most Tier 1 contractors have a corporate apprenticeship manager responsible for ensuring apprentices are on track to complete their frameworks. The quality of day-to-day mentoring at site level can vary significantly, however, and many of the contracts with the best completion rates also have the highest level of on-site mentoring support.

The BAM Ferrovial Kier (BFK) joint venture has experimented with a contract-level apprentice forum on its C435 Farringdon Station contract. Inspired by this example, two other contractors subsequently adopted something similar: the Dragados Sisk joint venture on its C305 Eastern Running Tunnels contract and the Alstom TSO Costain (ATC) joint venture on its C610 System-wide contract. The aim of these forums has been to help apprentices establish networks, share experiences, supplement their learning, offer their own suggestions for improving apprenticeships, and raise any issues of concern.

Figure 14 – Members of ATC’s Apprentice Forum on a visit to another Crossrail contract, at Paddington.

Maximising Sustained Employment

Chart 6 above also confirms generally high levels of continued employment after completion. This reflects the fact that most Tier 1 contractors with a corporate scheme treat their directly-employed apprentices as full members of staff from the moment of recruitment, and take them on with a view to employing them over the longer term. Once again, Contract A has been the main exception. As in other areas, most Tier 1 contractors have struggled to obtain reliable information about levels of sustained employment for apprentices employed by subcontractors.

Engaging trade contractors and labour suppliers

In the early years of the project, Tier 1 contractors were generally slow to secure any meaningful quantitative commitments from their subcontractors and labour suppliers. This largely explains the relatively low proportion of supply chain apprenticeships to date (28%). It also reflects the fact that Crossrail did not at the outset seek to impose on Tier 1 contractors any minimum share or quota of apprenticeships from the supply chain.With hindsight, this was possibly a missed opportunity, and since 2014 Crossrail has encouraged Tier 1 contractors to do more: for example, by emphasising the importance of supply chain engagement in the revised PAF and new Apprenticeship Award categories.

The situation has begun to improve from 2014, with some Tier 1 contractors – encouraged by the PAF – becoming much more active in negotiating explicit apprenticeship commitments from trade subcontractors and labour suppliers. The Alstom TSO Costain (ATC) joint venture has been especially successful in this regard, and now expects a majority of apprentices on its C610 System-wide contract to be delivered by trade subcontractors and labour suppliers by 2017.

These efforts garnered considerable recognition for ATC at the most recent (2016) Crossrail Apprentice Awards. This included an individual award for an electrical apprentice employed by BMSL, one of ATC’s labour suppliers, and a special commendation for its security contractor, Servest, in the Supply Chain Employer award. ATC also received the overall Tier 1 Contractor Award, the judges citing in particular its exceptional work in involving trade subcontractors and labour suppliers in delivery of apprenticeships.

Figure 15 – Mike Greenwood, ATC C610 Project Director, receiving his contract’s award as Crossrail Tier 1 Apprentice Employer of the Year in 2016.

Finally in addition to encouraging Tier 1 contractors to improve the quantity of trade contractor and labour supplier apprenticeships, the new PAF criteria now recognises as outstanding any efforts to improve the quality of supply chain provision, including recruitment processes, diversity, employment terms and conditions, mentoring, etc. So far, no Tier 1 contractor has been able to demonstrate this level of performance, however.

Optimising Training Provision

Employers on Crossrail have enjoyed a free hand in deciding which colleges to partner with for apprenticeship purposes. Whilst Tier 1 contractors are required, as part of their quarterly reporting, to identify which colleges apprentices are attached to, Crossrail has not sought to fetter their discretion by reference to college location, OFSTED rating, or any other criteria.

Whilst not a formal part of the PAF (even in its revised version), Crossrail has started recently to question Tier 1 contractors more closely about their rationale for partnering with particular colleges and the quality of these relationships. The specific information requested has included:

- Contractors’ criteria for selecting partner colleges;

- Contractors’ conscientiousness in monitoring college reports;

- Other evidence of collaboration between a contractor and a college (e.g., joint involvement in selecting apprenticeship candidates).

To date, the information received has been quite limited. In one instance, a Tier 1 contractor appears to have taken special care to ensure that its chosen college was relatively close to its work site, so that apprentices had a similar journey from and to home every day, regardless of whether they are at college or at work. For the most part, however, this subject appears under-explored – providing ample scope for clients and contractors to do more in future.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations

This paper has sought to describe the variety of apprenticeship initiatives on the Crossrail project. In particular, it has emphasised how Crossrail has attempted to influence Tier 1 contractors and their supply chains’ delivery of apprenticeships, both in terms of the number of apprenticeships delivered and (especially latterly) the quality of that delivery. This has involved close collaboration between Crossrail and contractors, as well as a willingness on both sides to modify approaches in the light of experience. So that other clients might benefit from this experience, outlined below are some of the main lessons that have been derived over the lifetime of the project, with specific recommendations in relation to each of these (see Recommendations 1 to 5).

Outside of Crossrail, the past few years have seen the profile of apprenticeships and the range of supportive public policies increase markedly. The current UK Government is committed to achieving 3 million new apprenticeships between 2015 and 2020. To improve take-up of apprenticeships on publicly-funded contracts, the Government has also issued new guidance on how to incorporate explicit apprenticeship commitments into all public procurements worth £10 million or above, and how to assess contractors’ bid submissions in relation to these commitments.[19] In January 2016, the Department for Transport and several client organisations jointly endorsed a new Transport Infrastructure Skills Strategy (TISS), incorporating client pledges to contribute 30,000 new transport infrastructure apprenticeships by 2020 to the Government’s overall 3 million target.[20]

Crossrail has welcomed all these developments and has been particularly active in supporting the development and implementation of the TISS. It is hoped that ‘top-down’ policy initiatives of this sort will have a positive overall effect, and strongly endorse the view that clients as a whole need to do more (see Recommendation 6). Nevertheless, for construction workforce skills development to become genuinely more sustainable, Crossrail believe that ‘bottom-up’ changes to underlying industry practices and institutions are also necessary. As such, Crossrail welcomes the forthcoming review by Mark Farmer, sponsored by ministers and the Construction Leadership Council, to examine the existing ‘construction labour model’ and ‘what business models and other arrangements could better support skills and skills pipelines in the sector’.[21] Government, clients, contractors and the industry’s workforce will all have a role to play in delivering the fundamental adjustments to existing practices and institutions that any effective industry reform programme is likely to require (see Recommendation 7).

Figure 16 – Oliver Trim, electrical apprentice at BBMV joint venture’s C512 Whitechapel Station contract

Impose Quantitative Apprenticeship Targets, but also Safeguard Quality

Undoubtedly, Crossrail and its Tier 1 contractors’ success in meeting and then surpassing the original target of 400 apprentices would have proved much more difficult, if not impossible, to achieve without specific numerical apprenticeship commitments written into contracts. In addition, the inclusion of these commitments has arguably helped provide a springboard for further collaboration between Crossrail and Tier 1 contractors over the course of the project, including the agreed introduction of broader measures of contractor performance in delivering apprenticeships during 2014.

For the most part, numerical targets do not seem to have compromised apprenticeship quality on the project. Partly this could be because the targets themselves were not especially onerous, and could, with the virtue of hindsight, probably have been set higher (a matter considered further elsewhere – see ‘Other Legacy Reports’, below). Crossrail’s minimum quality standards, also incorporated into the contracts, have probably also helped to reduce any incentives for contractors to sacrifice quality for quantity. These have included insisting on a minimum of 16 weeks before apprentices may be counted for target purposes, expressing apprenticeship targets in the form of ‘outputs’ rather than ‘heads’, and maximising regular employment status.

Other clients might, however, reasonably decide to impose higher quantitative targets and/or express these targets in the form of ‘heads’ (e.g. apprentices as a minimum proportion of the total workforce). If so, they should be careful, however, not to lose sight of quality considerations in the process.

Recommendation 1: Contractually binding apprenticeship targets are probably indispensable for any client wishing to improve the quantity of apprenticeship training undertaken by its construction supply chain. Clients should, however, take care to maintain an appropriate balance between quantitative and qualitative considerations. For example:

- Quantitative targets should be realistic, and not so onerous that quality ends up being sacrificed;

- If targets have to be expressed in the form of ‘heads’ rather than ‘outputs’, these should be supplemented by additional qualitative requirements (i.e., minimising the risk that organisations might resort to short, low-quality and/or irrelevant apprenticeship frameworks).

Figure 17 – Jordan Malcolm-Taylor, apprentice at BFK joint venture’s C435 Farringdon Station contract.

Consider the Full Range of Apprenticeship Priorities

With the benefit of hindsight, there would have been advantages in Crossrail defining a wider range of apprenticeship priorities at the outset of the project, and incorporating some or all of these into its contracts.

Recommendation 2: Clients should look to establish a comprehensive range of qualitative objectives in relation to delivery of apprenticeships. Detailed priorities may differ between clients and/or from one project to another, but should take into account:

- • The nature of the works (potentially relevant to the types and levels of framework that are most appropriate);

- • How the works will get delivered (e.g., the degree of dependence on subcontractors and/or labour suppliers);

- • Potential skills shortages (i.e., providing a rationale for preferring some frameworks over others);

- • Structural issues underlying poor apprenticeship performance (e.g. a lack of diversity, unattractive terms and conditions of employment, high drop-out rates, low levels of post-completion employment, poor selection of college(s) and/or weak employer-college links).

Figure 18 – Fatima Alghali, commercial apprentice at BBMV joint venture’s C510 Whitechapel and Liverpool Street Tunnels contract, and 400th apprentice on the Crossrail project.

Maximise Supply Chain Opportunities

On reflection, Crossrail would also have been in a stronger position to influence the quantity and quality of apprenticeships below Tier 1 if contractual requirements had been in place to facilitate this.

Recommendation 3: Where (as will often be the case) supply chains are likely to constitute a significant proportion of the total workforce, clients should give serious consideration to contractual requirements designed to maximise supply chain involvement in the delivery of apprenticeships – incorporating both quantitative and qualitative aspects. Depending on the circumstances, these might include:

- Minimum targets for supply chain apprenticeships. These might need to be set along a sliding scale, proportionate with the degree to which each Tier 1 contractor plans to ‘self-deliver’ works or rely on subcontractors and/or labour suppliers;

- Requirements on Tier 1 contractors to encourage trade subcontractors and labour suppliers to establish corporate apprenticeship schemes where none exist, and to support improvements in the quality of existing supply chain schemes.

Figure 19 – Rajeev Chavda, electrical apprentice employed by BMSL, a subcontractor working on ATC’s C610 System-wide contract, and winner of the 2016 Crossrail Advanced Infrastructure Apprentice award.

Manage Contractor Performance and Incentivise Good Practice

Even in the absence of explicit contractual provisions, Crossrail has had some success in promoting good practice and challenging contractors on broader aspects of their performance. On future projects, more demanding contractual requirements up front should go some of the way towards achieving the same goal. Clients must not, however, deceive themselves that strong contractual provisions are sufficient on their own to guarantee that project apprenticeship objectives will be met. Whilst some Tier 1 contractors involved with the Crossrail project have successfully used the experience to build up their capabilities in this area, others have not, and even where an enhanced capability exists it generally remains a fragile thing, dependent on the continued participation of a handful of committed and experienced individuals. Accordingly, even where future projects adopt wide-ranging strategic priorities and embed these strongly into their contracts, we still see an important role for active performance management by the client to ensure that contractors fulfil and ideally surpass their apprenticeship requirements.

Recommendation 4: Clients should put robust assurance processes in place to ensure contractors and their supply chains are complying with minimum quantitative and qualitative requirements, and provide incentives for exceeding these requirements. Examples include:

- Reporting requirements. These should include definitions of any quantitative measures of apprenticeship quality (e.g., drop-out rates, sustained employment rates, etc.);

- Performance management. Analysis of contractors’ reports should be used to inform subsequent discussions as part of a PAF, or equivalent, process. For example, high levels of drop-out should be investigated, since these might indicate serious weaknesses with recruitment, employment terms and conditions and/or site-level support;

- Facilitating innovation and sharing good practice. Clients on multi-contractor projects are in a strong position to coordinate sharing of information between contractors and highlighting good practice. Examples of the former might include encouraging contractors to share data on supply chain organisations that have provided apprentices on one contract, and might therefore be presumed to be capable of doing so on other contracts. Multi-contractor working groups could prove useful in fostering innovation, such as the joint development of new apprenticeship frameworks. Public recognition of good practice, exemplified by Crossrail’s annual Apprentice Awards, also helps incentivise and promote good practice.

- Commercial incentives/ penalties. We fully endorse the decision made by the Tideway project to link an element of contractors’ commercial bonus to achievement of skills and employment objectives. This incentive was not available on the Crossrail project, and would have proved helpful in overcoming instances of contractor non-cooperation or under-performance.

Figure 20 – Zoe Conroy, technician engineer apprentice at Laing O’Rourke’s C422 Tottenham Court Road Station contract.

Consider Intervening More Directly

As well as adopting different techniques for strengthening apprenticeship training indirectly (as outlined in this report), Crossrail has made various direct interventions with the same objective in mind. These have included work undertaken by Crossrail’s Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy (TUCA), such as the development of new ‘Trailblazer’ apprenticeship frameworks. Crossrail’s Jobs Brokerage has also sought to support contractor and supply chain apprenticeships, particularly in the area of recruiting from socially disadvantaged and traditionally under-represented groups. Whilst direct interventions of this sort fall outside the scope of the present report, they will be covered in more detail elsewhere (see ‘Other Legacy Reports’, below).

Recommendation 5: As well as influencing apprenticeship delivery indirectly, clients should consider whether and how they might intervene more directly: for example, through building training capacity, developing new apprenticeship frameworks and/or supporting jobs brokerage arrangements.

Figure 21 – Narges Afshari, engineering apprentice on Dragados Sisk joint venture’s C305 Eastern Running Tunnels project. Narges was recruited through Crossrail’s Jobs Brokerage, in partnership with Women into Construction.

Develop a More Consistent, Multi-client Approach

Individual client apprenticeship requirements should prove easier to implement and have greater impact if they are aligned and consistent with those of other clients. The Transport Infrastructure Skills Strategy (TISS) has created a model which clients in other sectors should now look to follow. Since, at the time of writing, it remains at an early stage of implementation, the TISS also presents a challenge to transport infrastructure clients themselves to develop the levels of coordination and management processes necessary to achieve their target of 30,000 new apprenticeships by 2020 and other TISS objectives.

Recommendation 6: Both within the transport infrastructure sector and outside it, client organisations need to prioritise major improvements in the quantity and quality of apprenticeship provision. So far as possible, these priorities should be clear and consistent with one another, and supported by robust contractual provisions and management processes to ensure construction supply chains deliver on their apprenticeship commitments.

Figure 22 – Crossrail apprentices join Crossrail Chairman, Sir Terry Morgan, and Government ministers, Patrick McLoughlin and Lord Ahmad, in launching the Transport Infrastructure Skills Strategy at TUCA in January 2016.

Address the Long-term, Structural Obstacles to Investment in Construction Skills

Ultimately, shortcomings in the provision of apprenticeships cannot be addressed in isolation from the serious, structural flaws in construction business models, employment practices and labour market institutions which underlie these shortcomings. Until a wider and more ambitious programme of industry reform is implemented, any improvements in apprenticeship provision achieved on major projects such as Crossrail are likely to prove incomplete and potentially short-lived. Client organisations have a contribution to make in tackling these wider issues, but so too do contractors, Government and representatives of the industry’s workforce.

Recommendation 7: All stakeholders in the UK construction industry have an interest and responsibility to tackle the long-term, structural obstacles to investment in construction skills. As the terms of reference for the present Farmer Review (above) acknowledge, this requires not only a rethink of training and development arrangements, but also a fundamental reconsideration of current construction business models, employment practices and labour market institutions. As well as overcoming systemic labour shortages, a wide-ranging overhaul of construction skills and employment systems could help the UK industry address other long-standing issues, including comparatively low productivity, poor quality, patchy uptake of new technology, over-reliance on immigration, and the limited appeal of construction careers to young people. Any review should take note of any distinctive institutional and other arrangements which enable other countries’ construction sectors to perform so much better than the UK. Specific matters for each of the industry’s stakeholders to consider include:

- Contractors: alternatives to current business models and practices, including the form and extent of subcontracting; how supply chain management techniques might be used to improve subcontractors’ delivery of skills objectives; and, what new labour market institutions, or improvements to existing institutions, might be required to support sustained improvements in industry performance;

- Clients: in addition to a more coordinated approach on apprenticeships (as per Recommendation 6, above), what broader support to provide for skills and employment good practice and the labour market institutions underpinning such practice;

- Government: what further steps can be taken to embed socially sustainable skills and employment practices through public procurement; whether current ‘employer-led’ models of vocational education and training are fit for purpose, or if (as in other countries) a broader range of stakeholders should be involved; and, what legislative and administrative changes (e.g., in connection with tax and employment status) are required to counteract construction’s currently degenerative competitive environment;

- Workforce: how workforce interests and perspectives are to be represented in the development of a more sustainable labour model for the construction sector, and the operation of this model through particular practices and institutions.

Other Learning Legacy Reports

The present report has covered one element of Crossrail’s Skills and Employment Strategy. Other related reports already posted on the Learning Legacy website include:

- An overview of the Crossrail Skills and Employment Strategy itself (published September 2016);

- An account of the establishment, operation and outcomes achieved by Crossrail’s Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy (published September 2016);

- A short assessment of the work of Crossrail’s Social Sustainability Working Group in disseminating good practice, including in relation to apprenticeships (published September 2016);

- An analysis of Crossrail’s implementation of the London Living Wage (published February 2016).

Further learning legacy reports, due to be published in March 2017, will also cover related themes, including:

- Implementing contractually-binding skills and employment targets;

- The Crossrail Jobs Brokerage;

- Crossrail’s Social Sustainability Performance Assurance Framework.

References

[1] Clarke, L. (2005), From Craft to Qualified Building Labour in Britain: a Comparative Approach, Labor History 46(4): pp.473-493.

[2] Prior, G. (2016), Only 12% of Construction Trainees Become Apprentices – Construction Enquirer, 16 May 2016.

[3] Richard, D. (2012), The Richard Review of Apprenticeships – School for Start Ups.

[4] UKCES (2012), Sector Skills Insights: Construction – UK Commission for Employment and Skills.

[5] See, for example: BIS (2013), Construction 2025 – Department of Business, Innovation and Skills.

[6] Behling, F and Harvey, M. (2015), The Evolution of False Self-Employment in the British Construction Industry, Work Employment and Society 29(6), pp.969-988.

[7] Chankseliani, M. and James Relly S., (2015), From the Provider-led to an Employer-led System: Implications of Apprenticeship Reform on the Private Training Market, Journal of Vocational Education and Training, pp.1-14.

[8] Loosemore, M, Higgon, D. and Aroney, D. (2012), Competing on Identity Rather than Price: A New Perspective on the Value of HR in Corporate Strategy and Responsibility, in Dainty, A. and Loosemore, M. [eds.], ‘Human Resource Management in Construction: Critical Perspectives’ – Routledge, pp.111-129.

[9] Druker, J. (2007), Industrial Relations and the Management of Risk in the UK Construction Industry, in Dainty, A., Green, S. and Bagilhole, B. [eds.], ‘People and Culture in Construction: A Reader’ – Taylor & Francis, pp.70-84.

[10] CIOB (2015), An Analysis on Migration in the Construction Sector – Chartered Institute of Building.

[11] Finegold, D. and Soskice, D. (1988), The Failure of Training in Britain, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 4(3), pp.21-53.

[12] Clarke, L. and Herrmann, G. (2007), Divergent Divisions of Construction Labour: Britain and Germany, in Dainty, A., Green, S. and Bagilhole, B. [eds.], ‘People and Culture in Construction: A Reader’ – Taylor & Francis, pp.85-105.

[13] ILO (2001), The Construction Industry in the Twenty-First Century: Its Image, Employment Prospects and Skill Requirements – International Labour Organisation.[14] Bowsher, K. and Martins, L (2011), London 2012 Apprenticeship Programme – London 2012 Learning Legacy

[15] Ofsted (2010), Learning from the Best: Examples of Best Practice from Providers of Apprenticeships in Underperforming Vocational Areas – Office of Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills.

[16] Ofsted (2010b), The Successful Training of Apprentices: Key Steps – Office of Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills.

[17] Ofsted (2012), Ensuring Quality in Apprenticeships: A Survey of Subcontracted Provision – Office of Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills.

[18] FISSS (2013), 21st Century Apprenticeships: Comparative Review of Apprenticeships in Australia, Canada, Ireland, with Reference to the Richard Review of Apprenticeships and Implementation in England – Federation of Industry Sector Skills and Standards.

[19] CCS (2015), Procurement Policy Note – Supporting Apprenticeships and Skills Through Public Procurement – Crown Commercial Service.

[20] Morgan, T. (2016), Transport Infrastructure Skills Strategy: Building Sustainable Skills – Department for Transport.

[21] CLC (2016), Construction Industry Labour Model Study – Construction Leadership Council.

-

Document Links

-

Authors

Anne-Sophie Blin MSc

Anne-Sophie Blin was the Lead Social Sustainability Officer at Crossrail from 2013 to end of 2016. In this role, she oversaw the implementation of the Crossrail Social Sustainability strategy, working with contractors to ensure they fulfilled their contractual obligations in relation to job creation, skills developments, promoting equality and diversity, and enforcing the London Living Wage. Before joining Crossrail in 2013, Anne-Sophie advised international property companies on developing and implementing strategies covering environmental and economic as well as social sustainability. She holds an MSc in Urbanisation and Development from the London School of Economics and a Master’s degree in International Relations from Sciences Po, Paris.

Andrew Eldred MA, MSc - Crossrail Ltd

Andrew Eldred was Head of Employee Relations at Crossrail until early 2017. His responsibilities included trade union engagement, oversight of contractors’ management of site employment relations, and delivery of apprenticeships and other skills and employment commitments. Before joining the Crossrail programme, Andrew held several senior employment relations roles in construction, including three-and-a-half years as the ODA Delivery Partner’s Industrial Relations Manager on the London 2012 Olympic Park construction programme. He holds an MA in Modern History from the University of Oxford and an MSc in Human Resource Management from Birkbeck College, London.

-

Peer Reviewers

Scott Young, Head of Skills and Employment, Tideway