Crossrail Procurement Delivery

Document

type: Case Study

Author:

Kevin Lloyd-Davies BA Post Grad DipFM (CEM) FRICS MBIFM, Martin Rowark FRICS, John Mead BSc(Hons) MSc MCIOB, Peter Sell BSc(Hons) MRICS

Publication

Date: 27/09/2016

-

Abstract

This paper sets out the origins and approach to Procurement at Crossrail, the development of the ‘Six Pillars’ of procurement, and how these were deployed to successfully deliver over £11bn of capital spend over a 5 year period.

-

Read the full document

Introduction

The acquisition of Crossrail was one of the largest regulated procurements undertaken in the United Kingdom in recent times. This paper sets out how the procurement of such a complex asset was achieved and the approach taken. The paper discusses the effective deployment of best practice and the lessons learned from previous infrastructure projects of national importance; and their evolution.

Crossrail was procured (from 2010) using best procurement practice employed on the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. This methodology was further developed at Crossrail and adopted by Infrastructure UK (IUK), forming the basis of a procurement module in the Project Initiation Routemap. Much of the Crossrail procurement learning legacy is incorporated in the procurement module which provides helpful guidance when initiating procurement on major programmes in the UK.

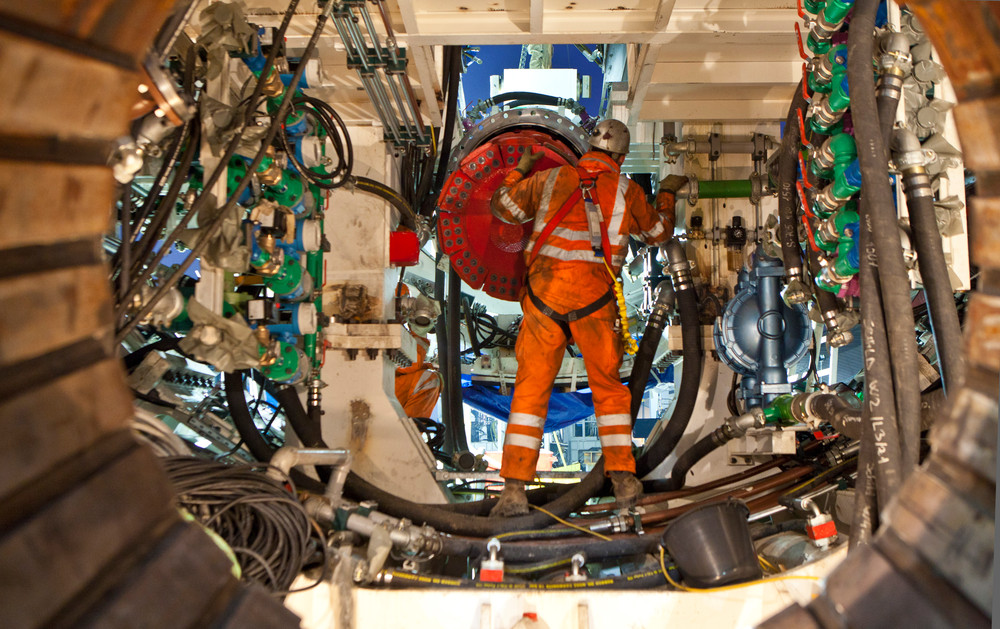

Figure 1 – Crossrail’s Tunnel Boring Machines were an early procurement for the programme

Olympic legacy

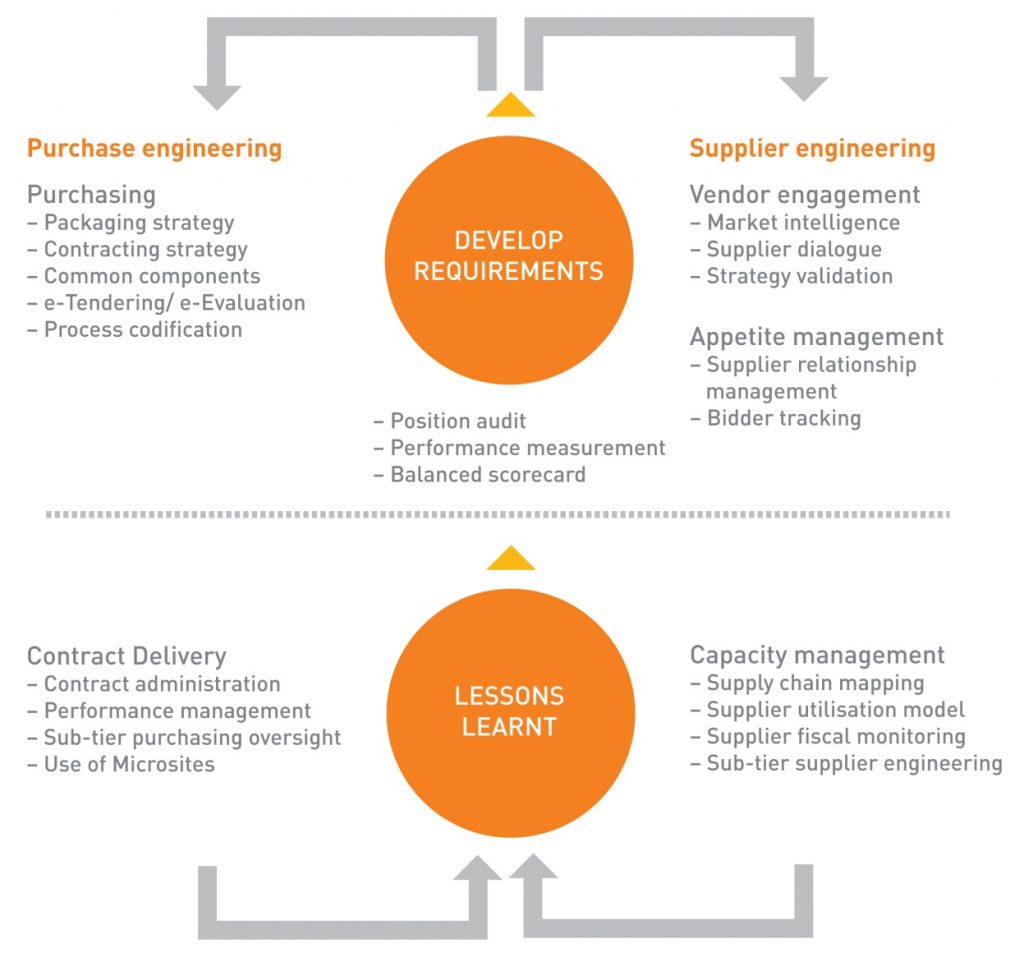

The London 2012 Olympics and Paralympics assets were procured using an innovative approach developed specifically to meet the programme requirements. It is now referred to as Purchase and Supplier Engineering (PSE) and articulated in the book “Programme Procurement in Construction, (Learning from London 2012)”; by Mead and Gruneberg. This approach offered another way of thinking about procurement on large infrastructure projects. Whilst the book did not claim to have invented a new approach it did point to best practice and how to deploy it. The PSE model is outlined in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 – Procurement and Supplier Engineering (PSE Model)

(reproduced courtesy of “Mead and Gruneberg” page 7, Programme Procurement in Construction, (Learning from London 2012))

The authors of this Crossrail procurement paper were also the instigators of the PSE approach at London 2012 and being credited for its success in the book. Bringing these people to Crossrail significantly helped to establish this best practice approach leading directly to the successes enjoyed by Crossrail today.

In its transition from pre- to post-Royal Assent, Crossrail considered how this complex scope was to be procured; and what was the best model which should be deployed. At the time the team wanted to secure similar results to London 2012 and employ best practice on the programme.

During transformation into a delivery organisation, and at the commencement of the procurement phase, it was realised, by Crossrail, that there needed to be a greater emphasis on the procurement structure. The highly successful PSE procurement approach was considered to be best practice and a suitable structure to employ at Crossrail. However, the PSE approach was not fully adopted until April 2011, following a 6 month development phase from October 2010. Crossrail needed to establish and put in place the appropriate processes and relevant experienced staff to deliver the model.

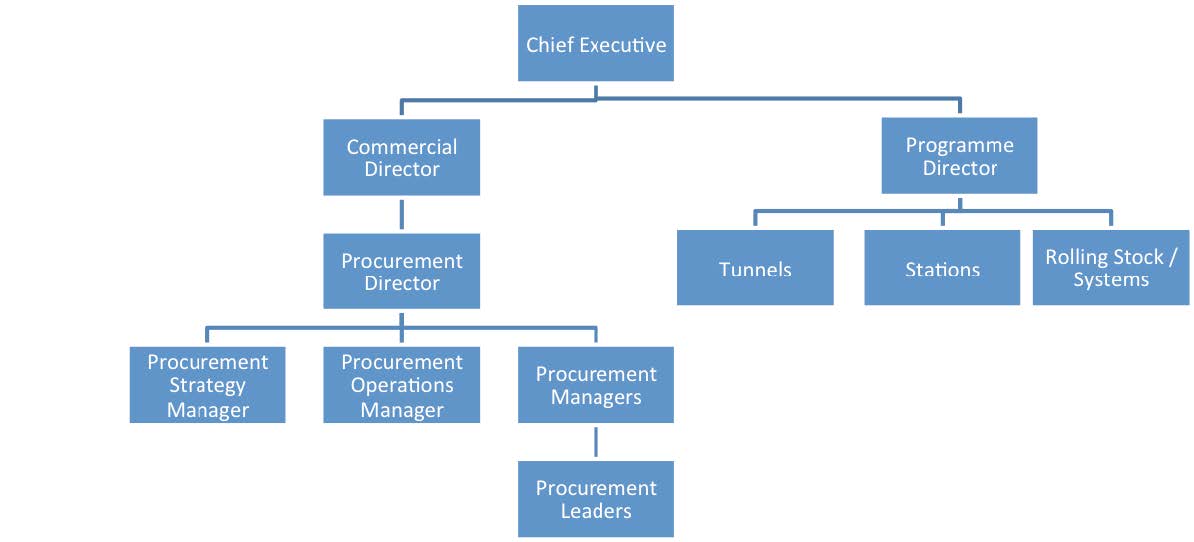

In response to this process and organisational need the Procurement Director, with the help of core team members, who were familiar with the PSE approach, put in place a procurement structure as shown in Appendix C.

The concepts developed in the PSE model were defined by the Crossrail core procurement team into a series of steps to successful acquisition. These steps were set down in a document called the “Procurement Code” which governed the deliverables required of the procurement function. These deliverables were further developed into the ‘Six Pillars’ of procurement and were deployed with full corporate commitment. These ‘Six Pillars’ were later to be incorporated into the IUK Project Initiation Routemap (procurement module).

Re-deployment of the London 2012 procurement approach

The procurement of Crossrail, prior to 2010, had followed a strategy evolved during the development phase of the programme. This strategy had been formulated for the purposes of attaining Royal Assent and, as such, had not been fully established from a delivery perspective. Procurement Policy, therefore, needed to evolve into the delivery objectives described below. This finally occurred by April 2010.

The packaging of Crossrail, in 2009, was very different from the model finally deployed in 2011; albeit elements would remain of the ‘old model’, as early works were required according to the programme delivery dates. When Crossrail began to procure the first major work packages it was still subject to an overlay of Governance from its key Stakeholders. This was later relinquished as the maturity of Crossrail was proven at Review Point 4 (RP4.2). With effect from May 2010, TfL delegated to the Crossrail Board full financial and procurement authority to implement the Crossrail Project and to establish a scheme of delegated authority within the Crossrail organisation. The process by which Sponsors assured themselves of Crossrail Limited maturity and gained confidence to provide delegated authority is explained in the Crossrail Learning Legacy paper ‘Lessons Learned from Structuring and Governance arrangements: Perspectives at the construction stage of Crossrail.

The procurement process was, therefore, subject to oversight by external stakeholders. This drove internal processes to have multi-levels of approvals resulting in inefficiencies. These inefficiencies were exacerbated by processes that were not using modern procurement techniques e.g. reliance on paper based systems rather than utilising the full processing power of the e-tendering systems. In essence, the procurement process had started from a difficult place.

Procurement of a programme the size and nature of Crossrail needed good project and production management using modern procurement practices. The programme complexity and schedule deadlines ultimately drove a need for ‘industrialised’ processes in procurement. A major change was, therefore, required and Crossrail set about mobilising a procurement production line to deliver construction procurement on an industrial scale.

A governance model would also be developed to support the PSE model and incorporated into the procurement code.

Procurement Policy, governance and organisational model

The Procurement Policy and its overarching objectives, as developed by April 2010, were in line with TfL’s policy and would be guided by the following objectives (extracts):

a) To deliver best affordable value;

Achieve best affordable value in delivering CRL’s high level objectives. Seek opportunities for efficiency and economies of scale across the Programme by working with TfL and industry partners. The achievement of best affordable value also requires that the procurement procedures and contractual arrangements support the delivery of related Government and TfL policies.

b) Establish effective governance and control;

Conduct the procurement activities in a manner that satisfies the requirements of accountability and internal control, fulfils CRL’s legal obligations, complies with financial constraints and effectively manages commercial risk.

c) Apply a standardised approach;

Provide and enforce effective, efficient and consistent commercial arrangements for procuring works, products and services of a common nature.

d) Build and maintain effective supplier relationships

Recognise that in order to achieve best affordable value appropriate relationships must be developed and maintained with suppliers and their supply chains.

The Crossrail Procurement Policy, mentioned above, is based upon simple principles which make clear statements about the approach it will take to meet its objectives. This approach was based on 33 Key Policy Principles and was established from lessons learned from other infrastructure projects. The lessons suggested that where Policy was extensively drafted, but lacked defining principles, they did not give the degree of leadership, direction and guidance needed to be influential and effective.

These clear and direct principles were used in the planning and delivery of the project. The senior management team established these early on to enable key decisions on strategy. These were made in a timely manner in order to set out the 2 key documents driving the programme, namely; the Delivery Strategy and the Procurement Strategy.

Having set the Procurement Policy with key principles a clear direction for the procurement strategy was now in place. Some examples of the key policy principles include:

Policy Objective

Key Principle To deliver best affordable value in delivering CRL’s high level objectives

KPP 2

Procurement activities delivering best affordable value for money

Build and Maintain Effective Supplier Relationships

KPP 5

Build and Maintain Effective Supplier Relationships

KPP 7

Formal market engagement strategy

Establish Effective Governance and Control

KPP 10

Ensure procurement is competitive, efficient, fair and transparent and in accordance with the Regulations

Apply a Standardised Approach KPP 13

Use of NEC suite with ‘light touch’ amendments

Build and Maintain Effective Supplier Relationships

KPP 30

Implement fair payment practices e.g. project bank accounts

The governance objective to “Establish Effective Governance and Control” was developed through the Crossrail Legal and Secretariat Team. This team implemented and managed the day to day governance related to delegated powers for decision making. Procurement was an integral part of this process reporting into the Board through the Procurement Sub-Committee (PSC) and latterly the Commercial and Change Sub-committee (CCSC). This sub-committee and authorised officers had delegated powers to approve plans and shortlists according to their levels of authority. Financial authorities and the authority to approve the award of contracts were vested in the Board without limit, and delegated to the PSC/CCSC up to a limit of £100 million.

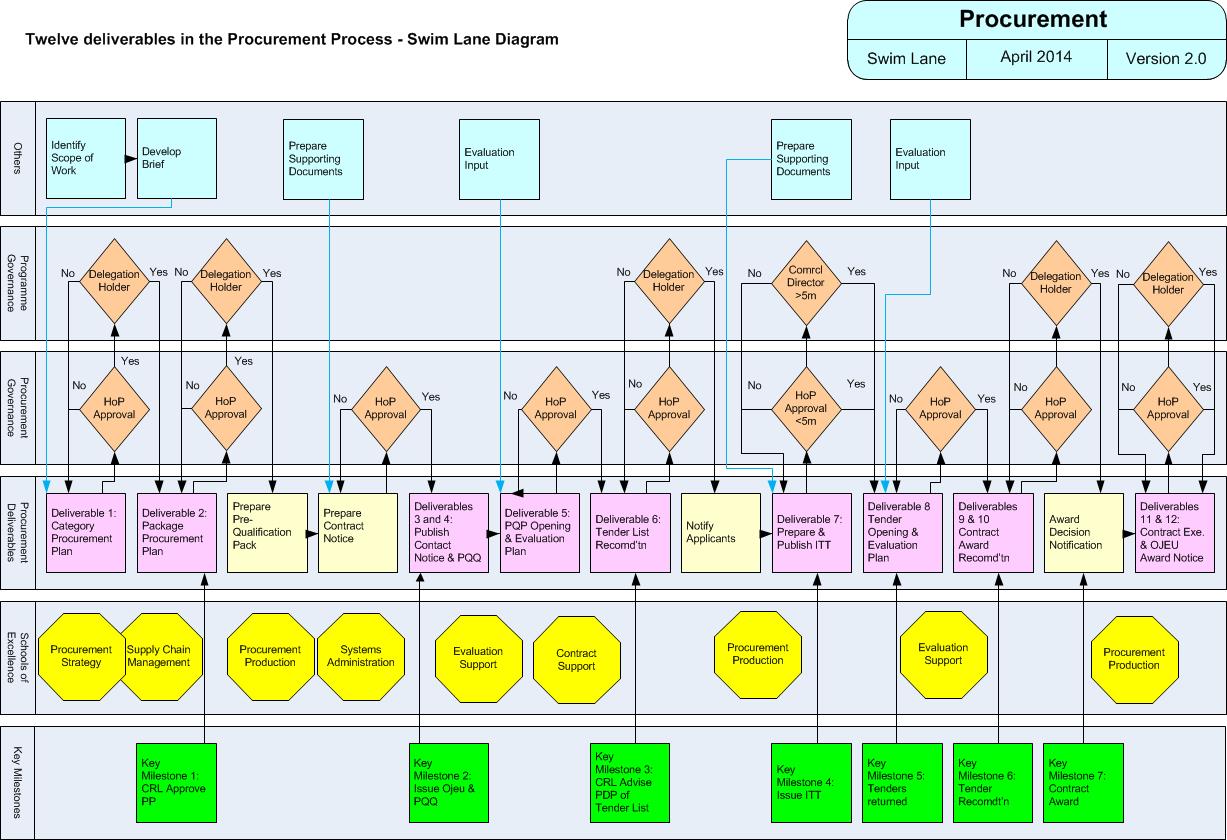

Clear instructions on procurement governance was developed and incorporated into a “Procurement Code” for compliance by the procurement team. This code contained a swim lane diagram of the 12 procurement deliverables which linked the points at which programme and procurement governance was required (see below).

Figure 3 – Procurement swim lane diagram

The flat governance structure without tiers of consultation and approval made governance of Crossrail remarkably efficient considering the significance of the decisions being made. It offered a highly robust process for challenge and accountability, whilst facilitating action where it was most needed.

In addition to the internal governance processes an independent Procurement Expert Panel (PEP) was appointed through the Institution of Civil Engineers. This panel provided guidance at the 3 gates discussed below and comprised of a Chair Person and relevant experts from a number of disciplines appropriate for the scope being procured. Typically, this included technical, legal, financial, and procurement members from senior positions within industry. The Panel would report and make any necessary recommendations to the Crossrail CEO following the pre-arranged meeting sessions (normally quarterly). The guidance provided was very useful in many instances and particularly informed our approach to the Rolling Stock procurement. Other major programmes are now adopting this independent review as means to test the procurement approach against the required objectives, identified risks, potential challenge issues, and scope being procured, and current Regulations,

Procurement governance operated on very similar lines to that of London 2012, whereby there were three key gates prior to the execution of the contract. These gates were underpinned by the 12 deliverables; all of which were implemented below Crossrail Board level (refer to the swim lane diagram above).

The 3 key gates were:

- The Category Plan or Procurement Plan

- The Shortlist

- The Award

These gates were recognised as outputs from the Procurement process as follows:

- Category Plans were put in place in accordance with the agreed Procurement Strategy. The categories e.g. Stations, Tunnels would explain and determine how the scope of works and services would be packaged and procured (a packaging strategy) relative to the market capacity and risk appetite. These would also align the delivery requirements of the programme. The plans were approved by the PSC /CCSC prior to the next stage of procurement.

- A detailed Procurement Plan would then be developed for each packaged project (identified scope) within the relevant Category Plan; recognising the requirements set out at high level. These became, in effect, a detailed execution plan. These plans were then approved if the recommendations were acceptable by the PSC/CCSC or, for lower value procurements, an authorised officer – the Commercial Director (up to £25m) or Head of Procurement (up to £10m).

- A shortlisting process was then used to determine the suppliers who were deemed ‘fit to supply’; this being a Pre-Qualification Questionnaire (PQQ) process based on the Procurement Regulations. Anonymity of suppliers was vigorously applied at this point with the competition process deciding the outcome. During the shortlisting and award processes, the anonymity of suppliers was vigorously maintained in order to ensure that decisions were made strictly in accordance with the criteria, rather than any subjective opinions. The shortlisting decision based on a review of the recommendation and findings was made by the PSC/CCSC or, for lower value procurements, an authorised officer – the Commercial Director (up to £25m) or Head of Procurement (up to £10m).

- The Award gate was a decision point at which authority was sought to commit to a contract based on the recommended offer received (go or no-go point). Depending on the value, either the Board or the PSC/ CCSC (up to £100m) or the CEO (up to £25m) or other authorised officers (up to £5m), reviewed the recommendation and decided either to approve or reject it.

Crossrail procurement was subject to the Utilities Regulations 2006 (Amended 2009) which imposed overriding treaty obligations on Contracting Authorities, including those of equal treatment and transparency. Therefore, the processes developed in the procurement code reflected both the internal and external governance compliance.

The procurement structure was similar to the model used on London 2012, whereby the transactional aspects of the procurement process were undertaken in a formulaic way (refer to the 12 deliverables and swim lane diagram), using techniques and principles of production engineering (Procurement Production Team). The same structure was adopted, in principle, by the Thames Tideway project following Crossrail’s lead.

The intent was to build a procurement machine that was able deliver industrial scale procurement based on the tried and tested approach at London 2012.

A detailed structure of the re-organised procurement team to deliver this model, as constructed at April 2011, is provided in Appendix C.

This team structure fitted into the programme matrix as shown below.

Figure 4 – Programme Structure

A clear line of responsibility was established to the Director for Procurement, or latterly Head of Procurement, who oversaw its effective and efficient operation.

This structure incorporated 3 main procurement activities which are detailed below.

Planning, strategy and assurance

Part of the procurement function had responsibilities for the oversight of procurement delivery, validating strategy and plans, and the 12 deliverables process. This was a small team of senior managers, who were highly experienced experts and were responsible for:

- Procurement policy, strategy and the ‘Procurement Code’ (setting out the internal and external governance and processes for procurement)

- Validating strategies and work plans

- Programme procurement risks

- Chairing the Standard Document Change Meeting (SDCM)

- Assurance of the processes set out in the code and compliance with Policy and strategy objectives

- Reviewing clarifications at contract award and notifications

- Independent debriefing of losing tenderers during the standstill period

- Managing internal and external Audits

- Liaison with stakeholders and external bodies

Procurement delivery

The procurement delivery (front office) element of the team comprised of senior procurement managers and leaders who were subject matter experts. They were embedded within the project delivery teams with the following characteristics:

- Procurement Managers were responsible and accountable for a procurement category and its delivery, for example stations

- Procurement Leaders were responsible and accountable for the end-to-end procurement of a particular project within a category, for example Bond Street station (they reported to the Procurement Managers)

- Assembling contract specific documents

- Obtaining approvals

- Liaising with key stakeholders to the category or specific procurement

- Liaising with procurement operations

Procurement Operations

Procurement operations, or the back office functions, were the production, or industrialisation, element of procurement activities. It consisted of experts in procurement systems, supply chain management and evaluation. The procurement operations team also consisted of a cohort of more junior team members who supported the Procurement Leaders. Some of these became professionally qualified and progressed to Procurement Leadership during their time at Crossrail.

The procurement operations team had the following characteristics:

- The operation and support of all e-tendering systems including evaluation software

- Developing and maintaining standard procurement documentation and ensuring the ownership of such by obtaining approval through the SDCM forum

- Managing the ‘Requirements’ from the functions into the documents

- Supply chain management

- Contract and legal support (liaison with the internal Crossrail legal team)

- Evaluation support

This model has, in the past, sometimes been referred to as ‘centralised procurement’. However, this is misleading, as the procurement delivery teams were embedded within project teams. The procurement team managed the procurement phase and facilitated the scope transaction on behalf of the project team.

It is important to note that the effective functioning of this type of unified structure depended on clear responsibilities and accountabilities being set out at the beginning. This was successfully achieved at London 2012 and Crossrail by the deployment of the ‘Procurement Code’ and a thorough understanding of the 12 deliverables required of the respective teams.

The strengths of this procurement model are:

- All procurement activity has clear accountability and line of sight to a single Director

- Strategic objectives are delivered consistently through the procurement organisation and project team e.g. Project bank accounts or skills and training

- There is visibility across the whole programme, particularly when managing the interfaces between packages and taking feedback from live projects

- Consistency and adherence to policy, thus mitigating procurement risk

- Having a consistent approach to tendering, allowing tenderers and project teams to become familiar with contract terms and Works Information

- Benefits in contract delivery across the whole programme so that project teams have a consistent approach to delivery, e.g. the same reporting requirements and strategic objectives on every project

- Avoiding duplication by using the back office to develop standard documentation; and processes

- Provides a consistent suite of contracts across the programme

- Change to standard documents, contracts and requirements are managed in a controlled way

There is no doubt that the approach was very successful. Crossrail procured its work contracts without a single procurement failure; or delay to the programme critical path; or formal procurement challenge.

However, there are a couple of learning points that deserve a mention.

- Firstly, the matrix model has 2 reporting lines, one through the Procurement Director, or Head of Procurement, and the other through the project team to the Construction Director. This can lead to “internal conflicts” particularly when the project team has not been fully briefed on the procurement process; as outlined in the Procurement Code. Having said this it has not been a particular issue on the Crossrail Programme.

- Secondly, a risk was identified at the transition stage from procurement into construction or service operation phase. There was a potential risk of losing commercial and contract knowledge from the procurement phase.

When a contract was awarded it was then passed to the project delivery team and its commercial function. A handover check list was prepared and all contract documents, PCGs, bonds and other pre-conditional documents were provided to the project team. Where any documents were awaited, typically bonds or PCGs, these were highlighted for action by the relevant person. The risk of knowledge loss was dealt with, in practice, by transitioning procurement leaders into those commercial roles, when appropriate to do so. In most cases they would have suitable commercial qualifications, as well as being CIPS qualified; e.g. Chartered Surveyors (MRICS), legal training (LLB or LLM), or engineering (MICE).

The governance protocols for Conflicts of Interest are also worth mentioning as their administration placed a significant burden on Crossrail . Crossrail has a Conflicts of Interest Policy which incorporates a ‘Perception Test’; a measure based on a reasonable perception by a third party as to the possible existence of a conflict. This test, which is more onerous than regulating only actual conflicts, has been relatively successful and served Crossrail well. The Policy, and the instructions to tenderers, placed the responsibility clearly on the tenderer, contractor, supplier or service provider to inform of potential actual or perceived conflicts. This ensured a high degree of protection against inappropriate behaviours in the supply chain with the consequences rejection or dismissal from the project. On the positive side it provided Crossrail visibility of who was in the supply chain providing services to multiple contractors or design teams.

The Key Steps to Success (The ‘Six Pillars’)

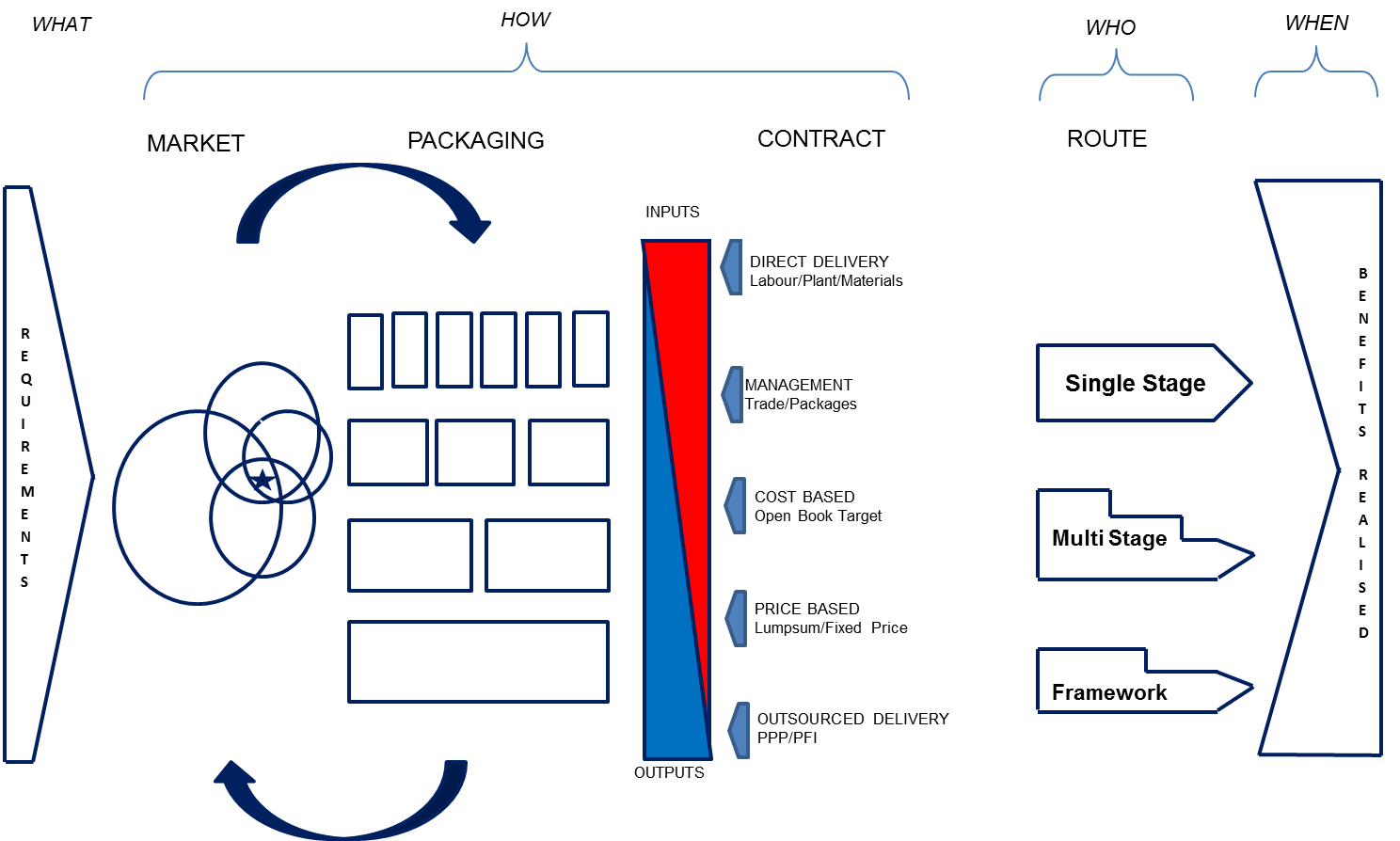

The PSE model, described previously, was used as the basis for procurement at Crossrail and further developed into a 6 pillar model. An explanation of this model is given below.

A major structural change to the procurement function was implemented in late 2010 to deliver against this ‘Six Pillars’ model. Those elements being:

- Understand and Communicate the “Requirements”

- Understanding and engaging the “Markets”

- A “Packaging” strategy (managing and optimising the interfaces)

- Develop a “Contracting” strategy (risk allocation and transaction)

- “Route” to Market

- Communicating the “Benefits”

Initially, there were some reservations as to whether the PSE model could be implemented at Crossrail, especially when it required retro-fitting into the existing governance processes. However, these were overcome by demonstrating clear gains through:

- Forward Planning (category and procurement plans),

- Managing risk early in the process, and

- Promoting efficiencies in the production processes.

This allowed a reduction in the procurement team size from 63 to 40 (30%), while delivering the same outputs.

Further evidence of this success was:

- Meeting all critical key dates ( no time lost on the critical path),

- Having no successful challenges, and

- Scope being procured within budget estimates.

This in turn has helped realise the expected benefits in the overall business case.

These pillars were later incorporated into the HM Treasury IUK Project Initiation Routemap (procurement module) as best practice. This was drafted by members of the procurement team and articulates the developed model based on the lessons learnt at Crossrail. Each of these pillars is discussed below.

Figure 5 – The Six Pillars Model

The “Requirements” (Pillar 1)

It is critical that the Client Organisation has a clear set of Requirements forming the basis of a robust business case early in the programme’s life cycle.

The Requirements should provide a description of the purpose and outcome being sought, identify the key deliverables, and set out timescales. These are needed to establish the main success criteria against which the programme will be measured.

The Crossrail Programme Functional Requirements (CPFR) set out a series of detailed outcomes to measure Crossrail’s success. These outcomes were broken-down, into the output requirements for each project.

Priority themes were developed by the senior management team to underpin delivery in the form of a Vision statement and Values as follows:

- Safety

- Inspiration

- Respect

- Collaboration

- Integrity

Work to align suppliers with Crossrail’s Vision has proven effective. The commercial performance and health and safety performance initiatives being particularly noteworthy. In addition, there has been success around skills and employment as well as SME engagement through the supply chain.

In general, the absence of a Balanced Scorecard at the commencement of procurement was a lost opportunity to fully align the ‘Requirements’. The specific requirements of each function e.g. Environment, were covered by the respective function. The Procurement function did not specify scope, nor determine cost, quality or schedule. However, it offered professional and respectful challenge (critical friend) to those with functional responsibility so as to deliver a successful outcome in procurement and administered change control around the requirements. This approach removed the potential for a lack of ownership in the post procurement environment, and the perception that the procurement transaction produced a contract remote from those in delivery.

The formulation and compilation of requirements, suitable for inclusion into contracts, was a significant task. The precision of language required for the NEC3 Works and Service Information presented a significant challenge to many specifiers.

This compares with London 2012 particularly in areas which ensured the requirements were consistent between functions and that the contracts were read ‘as one’. This was a task led by procurement and it focussed on document standardisation to bring about consistency in delivery. The scale of this task was underestimated and required significant input from all of the functions, including legal support.

The task at Crossrail was greater still as the degree of integration between packages, due to the systemic nature of the Crossrail asset, meant that not only contract consistency, but consistency between contracts, was vital. London 2012 was largely a centric programme of discrete projects (except the infrastructure); Crossrail is an integrated linear system of elements.

Whilst the importance of the precision and clarity of ‘Requirements’ would seem obvious it was often proven not to be the case. In the early days responsible functions did not recognise the priority for robust NEC Works and Services information, nor the requirement for clear and effective selection criteria, even though the contracts would be the primary driver of the supply chain. This was later remedied (2010 onwards) by establishing the Procurement Production Team (Procurement Operations) and a process for developing consistent and robust documents through the Standard Document Control Meeting (SDCM); chaired by the Procurement Strategy Manager.

The production of robust, precise and consistent criteria should be an absolute priority at the outset of any major programme to avoid inconsistency and confusion in delivery. This similarly applies to Works and Services information. It is a particularly important point; as compensation events may begin to arise through inconsistencies, or lack of definition may appear in different parts of the programme. These would usually centre on interfaces and design.

A key lesson learned from the “Requirements” pillar is for the functions to draft their documents based on a developed balanced score card linked to the Programme objectives, selection criteria and KPI’s. This should be done in a way that clearly and robustly articulates them to the project team, the supply chain and the suppliers.

Guidance feedback for Pillar 1:

- Review all aspects of the approved Business Case and clearly establish the Requirements.

- Engage and consider the aims and objectives of all stakeholders

- Establish a timetable for actions going forward

- Look to develop a Policy Document

- Consider developing a balanced scorecard to enable you to procure in a manner that delivers on all priorities and objectives[1]

The Markets (Pillar 2)

Between the Crossrail Act receiving Royal Assent in mid 2008 and mid-2010, Crossrail had undertaken limited market engagement activities with limited invitees. It was not until late 2010, to early 2011, that a Supply Chain Management function was created and a systematic approach to the markets was established. It was similar in nature and function to the team deployed at London 2012 with many of the ideas and intelligence analyses being used.

The scope of service they provided to the programme included following:

- Market engagement;

- Market and supply chain analytics; and

- Promoting economic sustainability.

This is not Supply Chain Management (SCM) in the delivery sense, e.g. monitoring production, but more to do with informing the programme of the markets’ position in critical areas. Particularly in 3 key risk areas:

- Market Appetite

- Capacity; and

- Capability

This intelligence was used for the development of Procurement Strategies, tender analysis and risk management during delivery. These 3 areas and the scope of SCM services are discussed below.

Market Engagement

Crossrail identified the Market environment in which they operated and then engaged with it at the earliest opportunity. This allowed Crossrail to test the Market on various options, or more specifically, gauge its reaction to risk transference, technical solutions, funding (RSD), interfaces, methodology and programme. Market appetite was then assessed and incorporated into the packaging strategy. Good responses indicated a healthy appetite and higher competition. This engagement was an iterative process so that intelligence was fed into procurement at various stages.

Early engagement with the markets had a dual benefit:

- A benefit to Crossrail in understanding what the Market can and cannot do (Capability), and what they will or will not bear (Capacity), in pursuit of an opportunity. More importantly, early engagement identified potential risks that Crossrail faced in the packaging strategy; and

- A benefit to the suppliers who were given an insight into the potential opportunities available to them, as well as the risks and rewards associated with securing that opportunity. The supply chain were able begin planning their tender resources in anticipation of the work and services pipeline; e.g. get ready and be fit to supply.

A key engagement strategy was to make Crossrail an entity easy to do business with by encouraging behaviours that were fair and equitable to both parties. Crossrail was also mindful that it did not present unreasonable expectations of risk transfer to the supply chain. This was reflected in the contract terms (very light touch amendments to the standard NEC form) presented to the Market for feedback. The cost of bidding was also upper-most in both Crossrail’s and the Market’s mind, so solutions that could minimise these would be attractive to the parties. This strategy, in conjunction with the economic cycle, elicited a response from the markets that was very positive and, therefore, no failures in competition or lack of response.

The market engagement exercise was approached in a methodical manner in the knowledge that a number of markets were to be engaged simultaneously; as well as exploring different markets at different stages in the lifecycle of the programme.

Market behaviour was influenced by Crossrail’s preparedness to engage. Part of this included selling the Project to the Market. It was done by engaging early with clear messaging and adopting a consistent approach. This in turn strengthened Crossrail’s understanding of the supply chain’s capability, capacity and appetite.

Gathering this market intelligence, at an early stage, was vital to the development of a robust and deliverable packaging strategy. It assisted Crossrail with identifying potential risks in delivery and to manage any potential shortfalls in capability, capacity and appetite. It also helped establish the market characteristics, for example, its boundaries, location and composition.

In addition, market intelligence gave an indication of how the Market would respond to the opportunity; e.g. Joint Venture (JV) solutions were proposed where there were shortfalls in capacity (production), or capability (skills), within individual companies. This in turn influenced the way the packaging strategy was constructed; e.g. by considering smaller scope boundaries, or acceptance that JV’s are the right solution to the proposed scope.

In some cases package scope was merged. This was articulated in the Category Procurement Plan for Railway Systems, for example; track, OLHE and system wide logistics being merged into the C610 package. Where niche markets were evident these packages were kept relatively tight in scope, for example; platform screen doors. For a given situation, market intelligence was key to providing input information for the packaging or procurement planning phase.

Market and supply chain analytics

Market and supplier analytics involved the Supply Chain Management (SCM) function monitoring the financial performance of critical suppliers in the chain. Approximately 7000 suppliers were assessed.

Monitoring was based on a range of data sources (around 100 in number) that allowed, by exception, reporting to be undertaken of the supplier performance on a daily basis. The performance measures included:

- Supplier Delinquency

- Supplier Solvency (ability to pay the supply chain)

- Percentage of turnover being secured (over commitment)

Supplier ‘Delinquency’ is poor trading behaviour and includes indicators such as: late payment to sub suppliers (evidence of CCJs being applied), winding up orders and other legal interventions. The tracking of delinquency by the SCM team was via available tools such as the Dunn and Bradstreet (D&B) delinquency scores.

The D&B Delinquency score predicts the likelihood that an organisation will pay its bills in a severely delinquent manner over the next 12 months. The Delinquency Score identifies organisations that are likely to pay late and helped Crossrail identify potential cash flow problems. Having the cash or liquid resources available to meet daily working capital requirements is fundamental to the business model of all organisations and was considered an important indicator of risk in the supply chain.

In addition, the D&B failure score gave the probability of insolvency over the 12 months period from the date of request. It is a relative measure of risk, whereby a score of 1 represents organisations that have the highest probability of failure, and a score of 100 the lowest. It showed how an organisation’s risk of failure compares to other organisations in the sector.

The early spotting of delinquency behaviour and insolvency was of a high priority and interest to Crossrail. Suppliers exhibiting abnormal behaviours suggested trading challenges and cash flow difficulties which may potentially impact delivery on site.

Another key measure, or analytic, was ‘Supplier Capacity’. Crossrail wanted to be aware of the ‘elasticity’ of capacity; or the risk of a supplier becoming thinly spread across the market.

Suppliers commonly, and understandably, are driven to achieve turnover and profit targets. This results in bidding the same capacity across a number of Clients well knowing that their likely success rates for submitted bids may be in the range of 1:3, or as low as 1:10.

Further down the supply chain there are more likely to be capacity issues and hence the need to select critical suppliers for monitoring. Capacity may be stretched to breaking point if suppliers are winning bids at the higher success rates and which may then impact delivery through under-performing.

Crossrail, as part of its responsible procurement approach, recognised that winning too much work, and over trading, was a real risk to the programme. More often, than not, this would be due to the lack of cash availability in servicing demand.

Promoting economic sustainability

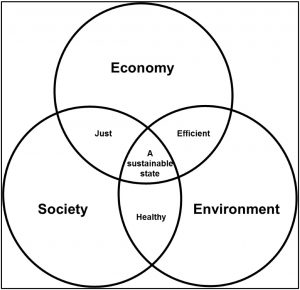

The triple bottom line sustainability model (see below) was deployed by Crossrail in 2011. The Socio/Economic and Environmental model formed the foundation of the programme’s sustainability strategy and served it well in guiding and directing a range of other policies, strategies and local initiatives.

Figure 6 – Triple bottom line sustainability model

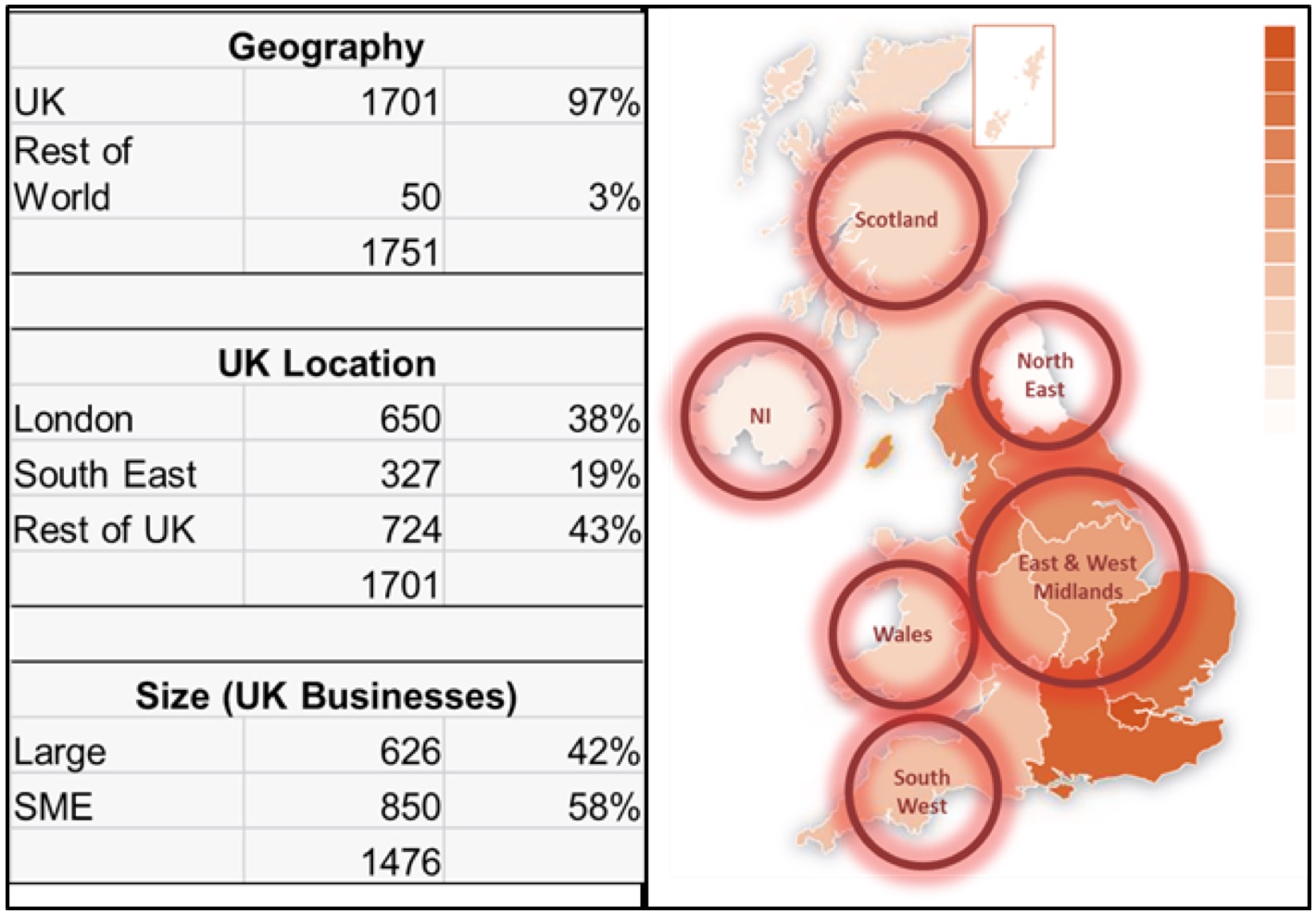

A number of regional events were organised to engage with companies across the whole of the UK. Some of these were more successful than others. There was a perception in the market that Crossrail was London centric and that firms outside the South East could not be competitive. These events and roadshows were Crossrail’s response to counter this perception by positively encouraging more engagement across the UK. The data collected by the SCM team provided evidence that Crossrail was having an impact across the whole of the UK and not just the in the South East. The team were able to provide data in a number of formats including supplier heat maps, tracing the Crossrail pound and opportunity tracking.

Figure 7 – Supply chain event

Figure 8 – Typical UK Heat Map and data collected by the Crossrail Supply Chain Management team

The SCM team led the economic sustainability initiatives, particularly the maximisation of opportunities for Small and Medium sized Enterprises (SMEs) and other suppliers in developing economic areas of the UK. During the procurement phase the SCM and wider client team engaged with over 8000 business representatives to advance these initiatives.

CompeteFor, a web based facility for identifying supplier opportunities, was used by Crossrail to ensure that the widest possible community of suppliers could compete for work. It was first developed and used at the London 2012 programme to supplement the OJEU process and provide direct access to opportunities through the supply chain. The CompeteFor portal, further developed at Crossrail, mainly focussed on the opportunities that sat beneath the first and second tier of the supply chain with the aim to engage SMEs. Many thousands of suppliers have traded using CompeteFor and it has provided a vehicle for the wider supply chain to track opportunities posted by the tier 1 and 2 contractors.

Awareness of the Crossrail opportunities was paramount to ensure that we were able to capture the full range of companies in a relevant sector. To assist companies to engage with Crossrail the SCM team produced supplier guides and detailed instructions on its website. They also provided information on the website about the pipeline of work or future opportunities, the stage at which procurement had reached, points of contact in the supply chain for suppliers, trade associations and other industry bodies with whom Crossrail were in contact.

Many of the supply chain analytics and techniques described above have have been used and developed on other major programmes including; Thames Tideway, HS2 and TfL.

Guidance feedback for Pillar 2:

- The Requirements need to be clearly defined for engagement; if not confusion will ensue market confidence and appetite will be lost.

- The risk profile (scope) should be modelled and reviewed to optimise engagement with the market (see packaging and contract strategy).

- Loss of appetite, or unexpected market behaviours, may result if the engagement is not considered carefully. This may lead to poor feedback, lack of competition, failure in market intelligence, and a poor packaging strategy.

- Know your Market. The project must have a good understand of the market environment in which they are operating.

- Understand the need to fully communicate the essential details of the project to the market; for example, timing of procurement and commencement on site, so that suppliers can match capability, capacity and appetite to the opportunity being presented.

- Use existing networks, trade associations, industry bodies, umbrella bodies etc. Treat all potential suppliers equally and fairly. Do not engage with suppliers outside of the procurement process once a formal process has commenced.

- Establish a clear engagement strategy, including the timeline and the format for supplier input.

- Early planning and communications are essential elements to deliver a successful engagement strategy. Communicate the full scope of the project or potential package in a consistent way, and where possible include some indication of value, however broad, while also highlighting current allocation of risk.

- Have a feedback process to ensure that any market intelligence is fed back to the relevant project team.

- Feedback can then be considered in the development of the packaging, contract and procurement approach.

- Once a tier 1 supplier is appointed ensure that the critical elements of the supply chain are identified so that capacity risk can be monitored and reported on a regular basis

The “Packaging” Strategy for the Programme (Pillar 3)

Packaging was at the heart of this procurement model and was fundamental to success in delivery. The purpose of having a packaging strategy is to plan and co-ordinate the scope to be delivered by different Markets to meet the Requirements of the business case.

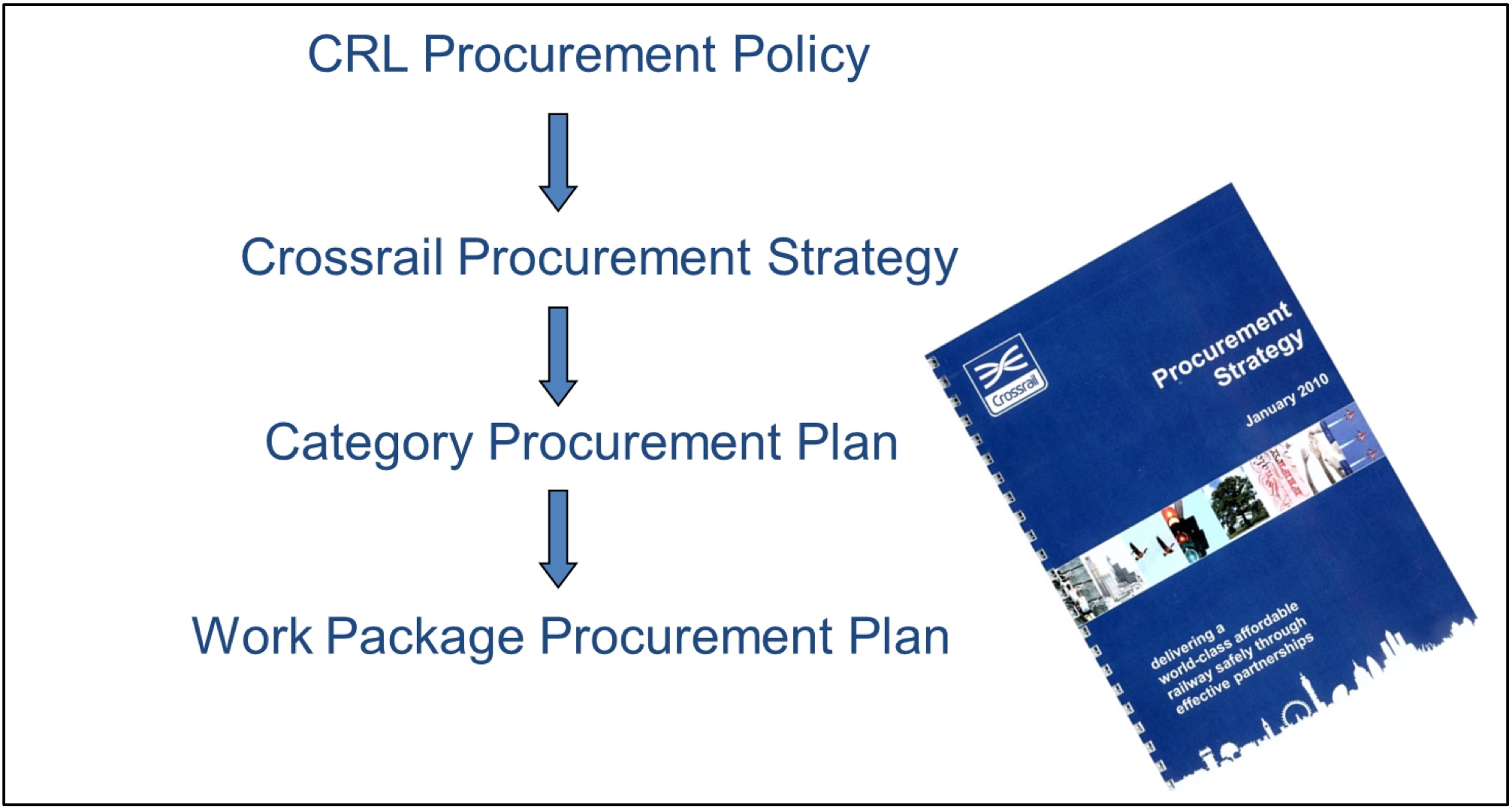

This packaging process was to bring detail to the Procurement and Delivery Strategies so that a Works Package Procurement Plan could be put in place (see below).

Figure 9 – Hierarchy of procurement policies and plans

Careful planning was required at an early stage to put in place a robust framework from which the asset, service, or goods can be delivered. It laid the foundations for delivery and influenced Crossrail’s approach to management.

Crossrail needed to establish its appetite for risk early on, taking account of its organisational structure, as this would have a significant influence on the packaging approach. It needed to determine what risks it was best placed to manage and which risks were best managed by the supply chain. Crossrail also needed to understand the risks associated with both soft and hard interfaces and the appetite for collaborative arrangements.

There were many drivers to consider when packaging the scope, but the key areas are as follows:

- The potential physical and contractual interfaces that would be created;

- The Market in which Crossrail operated;

- Technical characteristics of the Project (including – methodology and time constraints);

- Commonality; and

- The structure and availability of funding (Internal / PFI / PPP / concession initiatives).

As there are many ways to package the “Requirements”, ranging from multiple packages to a single large package, it was imperative that the Market was fully engaged to gauge the strategy’s appropriateness. This informed Crossrail about appetite, capacity and capability for the intended scope. On-going feedback and engagement enabled the packaging strategy to be continually refined, providing confidence that its approach was robust, and that the Market was able to deliver the Requirements.

The main function of the packaging strategy was to:

- Ensure that the scope is fully deliverable by the most appropriate market;

- Optimise the number of interfaces to meet the requirements and minimise risk at the best value; and

- Generate appetite for the maximum level of competition from the Market.

Clustering or Category Strategy

If the strategy leans towards multiple packages (more likely on most major infrastructure projects) then the Client organisation should consider using a clustering model to enable efficiencies in the procurement process. This has similar characteristics to the category approach on Crossrail.

The use of a clustering, or categories, approach enabled the production of standard sets of contract solutions (see Contracting) and allowed the control of the contracting process to remain at a programme level. Clustering, or categorisation, provided consistency in the tendering process allowing bidders to become familiar with documents, risk allocation, pricing requirements and the criteria used in assessing capacity and capability. Categories comprised works, services or products and were flexible enough to accommodate additional scope, allow the facility for collaboration, and provide access to commonality.

It was important to categorise similar elements of work, design, or services at a high enough level to allow effective communication with the target Market.

The key themes considered, when grouping scope into categories, were:

- The technical aspects of delivery, including methodology and technologies;

- Timing of the delivery;

- Physical location of the work or service in relation to others e.g. interfaces;

- The economic benefits;

- That the Market exists, is recognisable and able to provide healthy competition; and

- The capacity and resource is available in the supply chain to deliver the required quantity and quality.

The following categories were identified by Crossrail and formed the basis of the packaging strategy:

- Design

- Enabling and Advanced works

- Tunnelling

- Stations

- Systems

- Logistics

- Utilities

- Common Components

- Rolling Stock and Depot

- Surface Works

- Third Party Works

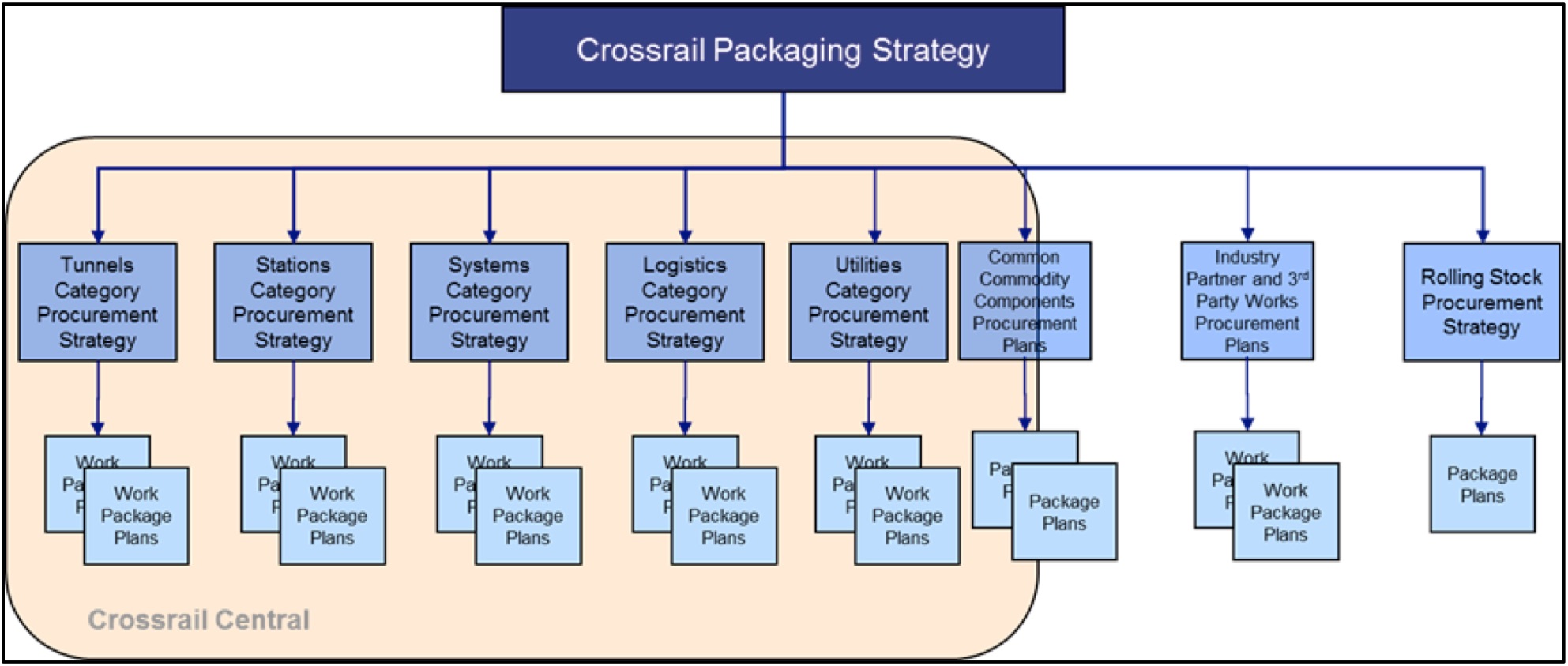

This is illustrated below (excluding design and early works).

Figure 10 – Crossrail Packaging Strategy

The packaging strategy influenced the programme in a number of areas:

- The creation of interfaces between packages and within packages;

- The value of the works and therefore the potential interested contractors or JVs;

- The scope of the works and therefore the type of Contractors required;

- The type, extent and cost of the client’s project management organisation;

- The level of design to be undertaken by the Contractor, and the corresponding approval process required of the client; and

- Health and Safety responsibilities including Principal Contractor (CDM) roles.

Design Packages

The Design Development Phase

Prior to 2005 the working assumption, coming out of the Montague report, was that Crossrail would be procured under “design and build” work packages. During the development phase [2] a decision was made to proceed, where possible, on an Employer’s design basis. This decision was taken to allow the design to be further developed without main contractors being engaged, to allow consistency of design, and to mitigate the risks around design integration, especially at interfaces.

During this phase the design was progressed under four Multi-Disciplinary Design contracts (MDCs). These designers took the design, for most elements, to RIBA D equivalent status.

The Detailed Design Phase

In preparation for construction, a number of design frameworks were procured under which the detailed design and construction phase design services could be secured. These frameworks panels were:

- A – Tunnels and Shafts

- B – Stations

- C – Portals

- D – Rail Systems

- E – Communications and Controls

- F – Architectural Component Design

- G – Materials and Workmanship Specification

These design framework panels reflected, in part, the categories mentioned earlier. This was to ensure that the best design resources were available for these elements. Secondary competitions were held (from the panel) for the civils and architectural detailed design to RIBA F, and for systems up to RIBA D.

Enabling Works Packages

Approximately £120m of early enabling work was required to maintain the programme schedule. This primarily encompassed demolition, minor civils works and utility diversions. Enabling works scope was also considered essential where the completion of long-lead items was required prior to the main works starting.

A number of frameworks were procured to support this requirement and the scope sourced through secondary competitions. Most of the 26 contracts were awarded as NEC3 Option A (lump sum) contracts.

Whilst these contracts were successfully completed, in retrospect, apart from demolition works, the programme may have benefited by having fewer packages with more flexible commercial arrangements; for 2 reasons :

- The effort and cost involved in tendering small packages was disproportionate to their value and led to interface management risks. This also led to increased costs for Crossrail, and bidders losing their appetite to bid.

- Emerging scope, in relation to enabling works, meant that contractors were asked to take on board significant additional scope. The NEC3 Option A arrangements were not ideal for this situation.

A positive outcome was that it gave the delivery organisation time to ‘bed in’ and to establish its management processes before the main works contracts commenced.

Main Civil Engineering Works

Crossrail largely inherited an assumed early packaging strategy for these works at the start of the implementation phase. It was quite granular with assumptions based on circa 40 separate main works contracts. The delivery team tested and reviewed this early packaging strategy against the key risks and interfaces.

Figure 11 – Preparing a TBM

Amendments were made, where progress and programme allowed, reducing risk and improving scope delivery. This process resulted in the number of packages being reduced through amalgamation. Ultimately, Crossrail ended up with the packages shown in Appendix A Table 1, below

Each package had a separate Works Package Procurement Plan detailing how the individual procurement would be undertaken. Some categories, such as the stations, were the subject of a single OJEU Contract Notice that allowed Crossrail and the contracting industry to rationalise the number of bidding opportunities and costs (see below).

Station Advance Works Contracts

These early packages consisted of diaphragm wall and piling works to allow the tunnels to pass through the station box construction at certain points on the route.

They came about from a perceived need to protect the programme critical path; taking account of the comparative maturity of design at the time. This created significant interface and completion risks with the following major civil engineering works. It was not an optimal solution as it placed Crossrail directly in the supply chain critical path.

It was considered, at the time, that this scope needed to be separate, because it was not possible to procure the stations in time to support the tunnelling programme. Designs for the stations were not sufficiently advanced to commence procurement.

With hindsight, earlier planning for this requirement may have allowed the works to be incorporated within the tunnelling contracts. Another option might have been to advance the station design to an early stage. In any event, more co-ordination and planning in the early design phase may have provided a better packaging solution.

Tunnels and Shafts

The three main running tunnel packages were determined by the tunnel drives. These were Western Running Tunnels (C300), Eastern Running Tunnels (C305) and Thames Tunnel (C310).

Tenderers were asked to submit bids for the Running Tunnels and Sprayed Concrete Lining (SCL) works separately, and also for a combined bid [3]. The SCL at stations was bid at the same time in packages for the West (Bond Street and TCR) and East (Liverpool Street and Whitechapel).

In the West, the Running Tunnels and SCL were awarded as a combined contract (scope package C300) with the interface risk being managed by the JV partners. In the East, the Running Tunnels work (scope package C305) was awarded separately from the SCL (scope package C510). This approach to packaging allowed the bidders to consider the best interface between the SCL and Tunnels, especially the construction sequence. In the East, where the scoped packages were separated, the interface management, between them, has been complex. This required additional Crossrail management resource.

Stations

A number of delivery options were considered for this category and are given below:

- A single package to deliver all stations

- Split packages West and East (division of stations)

- Individual station packages

The analysis, supported by market engagement, indicated that a competition could be run allowing the market to determine the risk they were prepared to take. To facilitate this Crossrail developed an approach which used one OJEU Contract Notice incorporating station Lots. These Lots were tendered over a period of time for each of the named stations.

A process was developed so that bidders were able to compete for their preferred station lots whilst capacity was managed by limiting the number of lots they could bid for. This enabled Crossrail to spread the risk across the market so that the contractors’ capacity would not be spread too thinly. The aim was to avoid performance and capacity problems further down the line. Over commitment by contractors is a common failure factor in our industry as bidding and winning large projects can quickly lead to capacity issues.

This approach also assisted the market to stabilise their JV arrangements, become familiar with each other’s appetite for risk, and focus on their bidding preferences. It may have also helped them with their resource planning and bid costs.

It is understood that a similar approach has been used elsewhere on subsequent programmes.

Logistics

Crossrail made a decision, early on, that river transportation would be key in its logistical arrangements. This was needed to reduce its impact on London’s road network and included both spoil removal and material deliveries. Provision had to be made in the contractual obligations to ensure this happened in the supply chain.

Crossrail entered into an agreement with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) to deposit large quantities of spoil at Wallasea Island and form a new bird sanctuary in the Thames estuary. Whilst there is no doubt that, from an environmental and safety perspective, this was a progressive decision, it placed a significant obligation on Crossrail to ensure there was a deliverable solution; e.g. the provision of stock pile areas, shipping, jetties, conveyor systems and earthworks engineering. This resulted in a number of critical logistics contracts being procured to manage and transport spoil from designated points.

All of these logistical arrangements had to be procured and put in place prior to commencing the major packages of work. This used a significant amount of Crossrail time and resource in scoping, specifying and packaging these requirements.

Provisions also had to be made in the tunnelling and other contractors’ methodology to incorporate these logistics. As a result significant supply chain interfaces were created.

These logistics packages consisted of:

- Contract scope package C806, under which a pontoon and conveyor was built at Wallasea; and

- Contract scope package C807 under which the spoil was transported to Wallasea from the Docklands Transfer Site (spoil from stations), Northfleet (spoil from western tunnels); and the Limmo peninsula (spoil from Eastern tunnels).

Figure 12 – Wallasea Island

Crossrail disposed of 7.5 million m3 of spoil through these logistics and tunnel contracts. However, in taking on responsibility, there came with it a large amount of risk. Crossrail learnt that disposal by river brought with it inherent risks which included:

- Stockpile management,

- Grading spoil for transportation,

- The difficulties of transporting clay by conveyors,

- The difficulties of shipping clay with a high moisture content

- Shipping availability (tides and loading restrictions),

- Removal of jetties and other equipment on completion, and

- Equipment design and interface.

Whilst the construction of the bird sanctuary has been a great success for both the RSPB and Crossrail, the operational problems took significant levels of management to make this a success. Early planning and risk evaluation of the interfaces may have drawn out some of these issues and perhaps arrived at another solution.

Systems (System-wide)

Early in the programme it was decided to retain the systems integration role and not to outsource this to a contractor. This was key when determining the packaging solution for the systems as a whole.

The technology packages consisted of:

- Signaling systems,

- Communication systems,

- Power, both permanent and track,

- Mechanical systems,

- OHLE,

- Track, and

- Platform Screen Doors.

These packages were integral to the central section and needed to be viewed as a single system with many interfaces. In this sense they required a different approach to delivery and packaging. Each system was potentially independent and had to function across the whole network.

When undertaking the initial scoping exercise it was deemed important to understand the nature of the required technologies and systems. A significant amount of work was done with the markets to understand their preferences and to optimise packaging scope.

The outcome of these multiple market engagements, and subsequent analysis, was that a single large ‘tunnel fit-out’ package would deliver the optimal solution; with a few exceptions. This was based on a number of factors which included; tunnel logistics, safety, alignment of sector skills, and track possessions.

This resulted in the scope package, C610 System-wide and Logistics, which combined Track, OHLE, Mechanical systems, tunnel equipment, structures, and logistics.

However, systems such as signalling and communications, being so critical to the operation of the railway, would be packaged and procured separately. Crossrail wanted to retain direct control over their design, quality, installation and integration.

Figure 13 – Track Laying

The interfaces between the stations and systems packages were recognised as being a critical risk early in the programme. However, these were not addressed until procurement of the systems packages commenced (after the tunnel and station packages were let). There is an argument that early planning of the rail systems scope would be beneficial to both construction and system packaging alike, so that the extent of the interface risks can be identified and managed appropriately

Maintenance

Scoping of maintenance was not fully considered until late in the procurement process as specific requirements were not readily available from the infrastructure maintainer (IM) at the outset. Although Crossrail has obligations to facilitate the provision of maintenance the IM should have been in the position to specify those requirements to meet the programme schedule; e.g. at the same time the project design and specifications were being completed. Unfortunately, the operational and service aspects lagged a long way behind the systems procurement and delivery needs. It was exacerbated by a change of the IM for the central tunnels in April 2012. This challenge is not uncommon and is something that needs to be addressed in future programmes as it has a considerable impact in delivery.

It is essential to mobilise the operators early in order to have a clear understanding of the operations strategy. This in turn will allow the maintenance approach to be developed in context with the design specifications.

Rolling Stock and Depot

The procurement of the rolling stock and depot is considered to be sufficiently complex that it warrants its own dedicated learning legacy paper for future publication: ‘Procurement of Rolling Stock, Depot and Associated Services’.

Common Components and Commodities (C3)

The Common Components and Commodities, or the C3, initiative was adapted from a similar initiative at London 2012. Where appropriate, the ODA directly procured materials and components to improve productivity, reduce transportation, centralise supply and reduce supplier costs. This included, for example, a concrete batching plant, bulk timber supply, on-site tools, and waste handling. The opportunity to aggregate demand, with the potential to gain leverage in the market, can be attractive to clients and was recognised by Crossrail in the C3 initiative. It focused on three simple tests:

- ‘What is it?’ – the definition of the component or commodity,;

- ‘Why should we get involved?’ – the business case;

- ‘How to acquire it?’ – the procurement strategy and options.

Crossrail set up a panel to sift through the multitude of components and it became clear that many components became hard to define. The biggest challenge was that components appeared to be the same but often be quite different. Additionally, logistics and supply chain intervention risk came into play.

For example; many of bulk materials would be subject to multi-site deliveries and not suitable for logistics from central depots; the approach used at London 2012. Crossrail was spread over approximately 40 sites and made the benefits difficult to realise.

Figure 14 – Common Components – visualisation of platform benches at Abbey Wood

Another example was whether steel could be purchased as a bulk commodity. Crossrail was aware of the tonnage required but it was spread over many types and grade of steel; in columns, reinforcement bars, mesh etc. When the exercise was completed it was established that the risk of stepping into the supply chain far outweighed any small benefit which may have been obtained.

Ultimately, the sifting process, usually by quantity and value, identified very few instances of aggregation yielding any large benefits.

It became clear, relatively quickly, that the risks attached to materials procurement were high when taking account of the impact of delivery failure. This was exacerbated by the programme being spread over a wide geographic area in a complex city environment. The aggregation of supply logistics could not be achieved easily, unlike London 2012.

There were a few significant cross-cutting acquisitions, these being, lifts, escalators, uninterruptable power supply (UPS), building management systems (BMS) and lighting control systems. These were procured directly by Crossrail as frameworks for use by the Tier 1 contractors. They were deemed essential systems that required consistency across the programme.

There was also a joint initiative with Transport for London, specifically London Underground, to acquire a single model for lifts and escalators, each with a whole life maintenance package. The new common specification, escalators in particular, proved a significant challenge for London Underground. However, this was overcome by cooperation and good engineering leadership. The joint initiative has proved to be a major step forward for LU in rationalising its assets on the Underground.

The railway will benefit from this collaboration during its operation as it will share the same maintenance and replacement contracts for 30 years.

The C3 approach is being used by Transport for London as the basis for their Category Management Strategy and developed into a best practice model for use across their broad portfolio.

Guidance feedback for Pillar 3:

- Obtain the total scope and requirements to facilitate a good packaging strategy.

- Properly assess the package boundaries and ensure that the correct delivery solution is procured. Key deliverables should be accounted for; e.g. date for operational commencement.

- Determined the packaging strategy in advance of the contract.

A common error is to jump straight to the method of contracting without considering the wider drivers of packaging.

- The strategy needs to consider the drivers which affect Organisation’s appetite for risk. These must be properly assessed in order to develop the appropriate risk profile. The Organisation’s approach, attitude and aptitude to risk management must be considered, along with their fitness to support that approach.

- The Organisation should be structured to manage the proposed packaging strategy.

- Having considered the appetite for risk, determine a suitable allocation of scope.

- The Market engagement should be designed to assist with this, if done correctly it will help determine appetite in the market and develop a robust competitive environment.

- Particular focus should be given to interface management and the risks associated with it. There will be varying levels of technical, commercial, and operational issues arising from the chosen packaging strategy which will require managing.

- Given sufficient attention to the interfaces and associated risks. They will impact market appetite. Soft interfaces may be managed through collaborative behaviours and the use of alliancing and partnering.

- The Client Organisation should use the packaging strategy to leverage the supply chain to maximum effect.

- Sell the Project in the market engagement phase and make the packages attractive to the market. This ensures healthy competition and successful procurement.

The “Contracting Strategy” – Risk Allocation (Pillar 4)

Crossrail elected to use the NEC form of contract as the preferred Government contract of choice, being considered best practice. This was set-out as a Policy requirement in the Procurement Policy Document. There are a number of reasons for this amongst which are, the principles of mutual trust and cooperation, and robust auditable contract management processes.

The NEC form enabled Crossrail to use a suite of options appropriate to the risk profile it wished to transact. These, essentially, are based on the level of design and specification maturity, and or, schedule necessity. This paper does not discuss the merits of these options as these are well documented elsewhere.

The contracting strategy is the process of allocating the risk to the party best placed to manage that risk, having determined the Client Organisation’s appetite, and how much the market is willing to bear (established during the packaging phase).

The main function of the contracting strategy was to:

- Ensure that the risk is allocated to the most appropriate party best placed to manage the risk

- Determine that the Market is able to bear the proposed level of risk

- Select the most appropriate form of contract to manage that risk

Risk allocation at Crossrail was dependent on whether the delivery requirement was input or output based, and the level of fixity. The level of fixity was, in most cases, related to the level of design or specification against which the contractor was expected to deliver.

When considering risk allocation Crossrail undertook an assessment using the basic principles of whether to ignore, accept, avoid, reduce, transfer and exploit. These were the determinants in the underlying approach. They generally fell into 3 categories or classes of ownership; Crossrail’s risk, shared risk and the contractor’s risk. The outcomes would then be assessed against the most appropriate risk profile and the option selected.

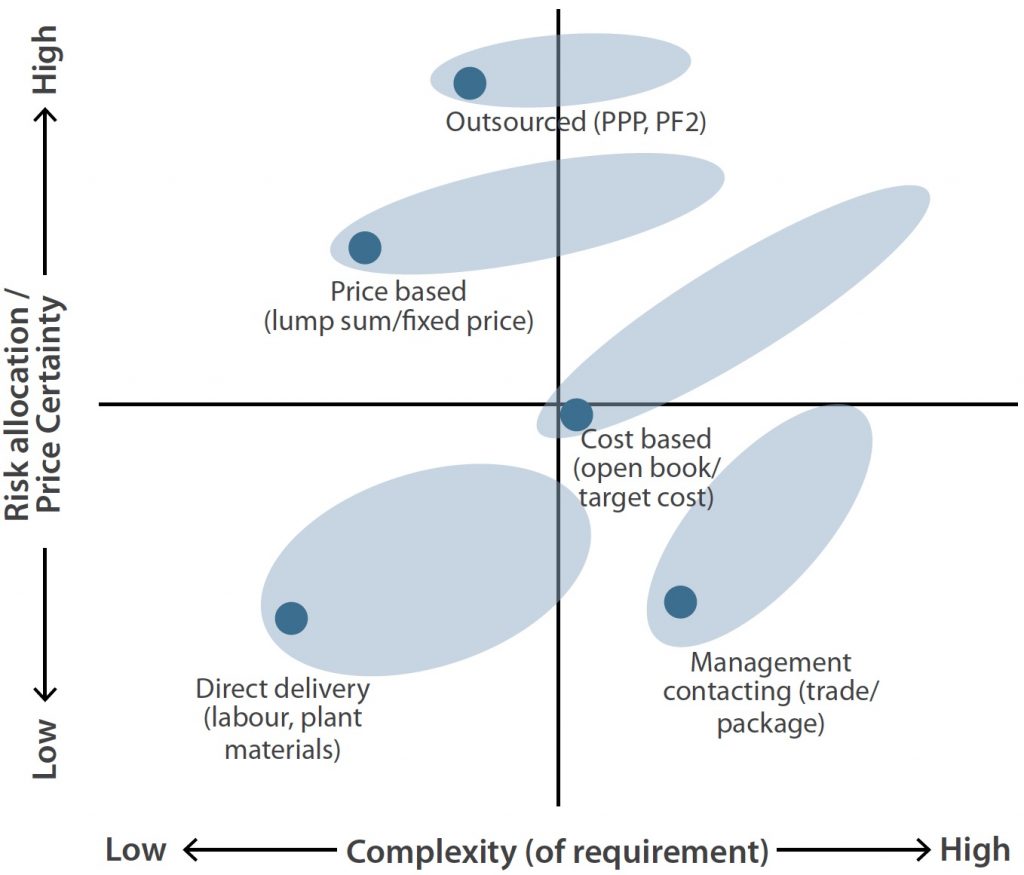

Crossrail recognised that there are only a limited number of generic options to contracting. The spectrum moves from Outcome/Output based service models such as PPP and PFI, to input based models with the direct purchasing of labour, plant and materials. Other approaches pivot around price or cost based contracts, such as lump sum fixed price, or cost reimbursable (often with incentivisation).

It was with this contracting palette in mind that Crossrail considered its options for optimising risk transfer. The diagram below is reproduced from the IUK Routemap Procurement Module, page 28, which was developed to illustrate these points.

Figure 15 – Risk allocation vs complexity – contract choice

(reproduced from IUK Routemap Procurement Module)

Guidance feedback for Pillar 4:

- Reflect the packaging strategy’s intent.

- The Client Organisation and the Market appetite for risk must be established before a Contracting Strategy is finalised.

- Allocate the risk to party best placed to manage that risk.

- Consider a classification structure to simplify the risk selection profile.

- Select the most appropriate contract form and, if possible, have a flexible and consistent approach. Consider a suite of contracts.

- Establish the level of control required in the contract; is the Client Organisation fit to administer the contracts when implemented, and is the senior management team supportive of the approach

- Consider incentivisation, collaboration and associated behaviours.

- Take account of soft Requirements and the balance score card.

The “Routes” to Market (Pillar 5)

The route to market is the last stage of the procurement process before contract award. It is characterised by the method of down-selection and the trade-off between competitive leverage, competitive advantage, the degree to which the requirements are developed, and the processes used in procurement.

There are various routes to market, but they are not discussed here; for further information refer to the IUK Routemap procurement module which was developed from the Crossrail and London 2012 experiences.

The ‘Route’ to market was governed by the Utilities Regulations. The preferred route selected was based on the ‘Negotiated’ method and the MEAT (Most Economically Advantageous Tender) approach to best value.

The down-selection process and award criteria were determined very early in the programme and whilst these evolved over time, following feedback, they were not departed from. The Prequalification protocol determined the bidders who were fit to supply and the subsequent competitions were successful; being without failure or challenge from the supply chain.

Over 80% of Crossrail’s successful bidders offered the highest quality bid and this was a significant success over the risk of a lowest a price competition. Subsequent feedback indicated that market conditions, at the time, were such, that bidders may have been overtly competitive in pricing their work. This, potentially, may have affected behaviours during delivery.

The Crossrail procurement team focused on the obligations of equal treatment and robust processes; as the impact of a successful challenge could well have had very damaging consequences to the overall critical path of the programme. The route to market and procurement planning was critical to the success of programme delivery. Appendix B provides details of this procurement planning data and was commonly referred to as the ‘Tender Event Schedule’. This was another tool taken from the London 2012 programme to manage and track procurements with great effect.

The approach taken at Crossrail recognised that a trade-off existed between the development of bids before contract award and the amount of competitive leverage that could be obtained for delivery. The cost of design and production planning during the bid process could have been prohibitive and reduced appetite. This in turn may have added unnecessary risk allowances into the bids. In an effort to achieve a balance Crossrail introduced a process, post-award, called Optimised Contractor Involvement (OCI). This methodology allowed Crossrail to continue the competitive leverage into delivery by offering the opportunity to review and optimise the design, work production, (methodology) and innovation in the supply chain. This was a joint exercise carried out within the first 90 days of commencement. It also provided an opportunity for collaboration and early team building.

It helped to execute contracts promptly and efficiently, a major benefit, considering the scale of the contracting effort and the number of interdependent contracts being let.

The process was used mostly for the Tunnels and Stations contracts and was based on a two stage tendering competition (shortlisting followed by submission of tenders) with an employer’s design to a pre-determined RIBA stage; either D or F (refer to previous section, Pillar 3).

In practice, insufficient time was given to the process, and whilst the collaborative working and on-boarding aspects were successful, in many respects, innovations or production efficiencies, and thus savings, did not fully materialise. In many cases, the process was seen as an opportunity to make-good design inconsistencies or underestimates of methodology risks, leading to increased cost.

As mentioned previously (Pillar 3), the maturity of design was a key factor in the competition. Whilst Crossrail had made a very early determination that an Employers design strategy would be pursued, this strategy had become challenging by the time the station packages were contemplated. This was largely due to the progress in design and the challenge of integrating this complex undertaking. This led to an emerging approach incorporating a hybrid of employers design, and a contractor’s design and build. The later Systems contracts employed a contractor design approach.

A key lesson from this early design assumption is that the RIBA Plan of Works stages are insufficient for the complexity of a systems asset such as Crossrail. The complexity of scope and the challenge of design integration are often underestimated. The RIBA definitions were not finite in a design context and the following design responsibilities became subject of debate. The articulation of the design responsibilities requires careful thought in future programmes to avoid potential misunderstandings in delivery.

A key document in the tendering process was the ‘Wrap-Up Letter’. This document set out all of the clarifications and agreed changes to the tender submission and was issued to the bidder, or bidders, for signature as to the true position reached prior to the finalisation of the Contract documentation. It was used to articulate the offer that was open for acceptance in order to remove any uncertainty as to the terms and content of the contract which would be formed and preclude any commercial gamesmanship after announcement of intention to award. This enabled Crossrail to execute over 90% of the contracts within two weeks of award decision.

The route to market, or programme of procurement, was completed without a single delay to the critical path. It was considered a significant achievement not only by Crossrail but by the independent Procurement Expert Panel, appointed by the ICE in an advisory capacity. The route to market was efficiently carried out by adopting processes set out in the procurement code (see the section on governance above); thus giving the best start possible start to the teams on site.

Guidance feedback for Pillar 5:

- Consider the cost of bidding to both you and, most critically, your suppliers in advance of selecting the route to market;

- Put in place contingency arrangements should you fail to achieve the required risk transfer;

- Develop and understand the level of leverage that needs to be maintained to achieve the desired placement of risk;

- Consider the appropriateness of the Route to market to support delivery of the Requirements;

- Determine the balance that must be struck between level of risk transfer and the time needed to conclude the process;

- Establish the impact on the Market of a down-selection process; for example, awarding a framework will mean that there is a closed market for the tenure of the agreement; and

- Be aware of the limitations and constraints imposed by the EU Regulations, or other procurement governance requirements.

The “Benefits” Communication (Pillar 6)

Like the London 2012 Olympics before it Crossrail leaves a true legacy, not just as tangible infrastructure but also in intellectual property. Programmes can suffer from the natural and sometimes commercial instinct to create something new, a platform to receive recognition upon. This need to ‘reinvent the wheel’ stifles progress in many ways rather than evolving and innovating through best practice (importantly lessons learned). Programme teams (particularly pop-up programmes) go through the equivalent of a business start-up in almost every case.

This Learning Legacy paper is a clear example of Benefits Communication, in that it shares the lessons learned to inform others, so that they may take the most effective actions upon their own projects or programmes.