Lessons Learned from Structuring and Governance arrangements: Perspectives at the construction stage of Crossrail

Document

type: Case Study

Author:

Chris Croft BEng, Martin Buck FICE FRICS, Simon Adams BEng CEng MICE APM

Publication

Date: 26/04/2016

-

Abstract

The delivery model for Crossrail has proved successful and could form a template for other large and complex government-funded infrastructure projects. The independence and autonomy delegated to Crossrail Limited by sponsors, separating them from the delivery body, has provided an effective solution to support the realisation of project outcomes to date. This has been enabled by governance arrangements that have stood the test of time and the clarity provided through the project agreements with respect to the allocation of responsibilities and management of risk. Lessons learned from the Crossrail project indicate that the model could be further developed to focus on the integration of infrastructure projects with associated regeneration and growth; to include more formalised governance to align benefit realisation; to bring enhanced focus on controlling sponsor initiated scope change and on through-life asset management.

-

Read the full document

1. Executive Summary

The delivery model for Crossrail has proved successful and could form a template for other large and complex government-funded infrastructure projects. The independence and autonomy delegated to Crossrail Limited by sponsors, separating them from the delivery body, has provided an effective solution to support the realisation of project outcomes to date. This has been enabled by governance arrangements that have stood the test of time and the clarity provided through the project agreements with respect to the allocation of responsibilities and management of risk. Lessons learned from the Crossrail project indicate that the model could be further developed to focus on the integration of infrastructure projects with associated regeneration and growth; to include more formalised governance to align benefit realisation; to bring enhanced focus on controlling sponsor initiated scope change and on through-life asset management.

2. Introduction

This paper was commissioned by Crossrail to identify the lessons learned from the structure and governance of the Crossrail project as an example of “robust delivery of a government funded mega-project in a complex stakeholder environment”. The value in capturing these lessons learned has been highlighted by the adoption of many of the characteristics of the Crossrail solution in a number of other UK Government funded large infrastructure projects including High Speed 2.

The paper first sets out the context of the project and then describes the solution and factors which influenced the design of the structure and governance arrangements, before identifying a number of lessons learned. The scope of the paper focuses on three specific areas:

- Sponsor/client and stakeholder integration – how the project sponsors and wider stakeholders were organised to support effective delivery of their objectives / outcomes

- Delivery structure – the form and characteristics of the delivery body to provide a fit-for-purpose vehicle to deliver the infrastructure (the output)

- Governance arrangements – arrangements which provided sufficient freedom and incentivisation for the delivery body to manage delivery and risk to meet the sponsors’ objectives.

Whilst the ultimate assessment of the structure and governance is best judged following completion of the project, this paper sets out perspectives at the current stage of the project where Crossrail Ltd (CRL) is completing the construction phase, integrating systems and transitioning to commissioning and operations. There is value in revisiting the lessons learned and how the governance arrangements have supported the project through commissioning and transition into operations once this phase is complete.

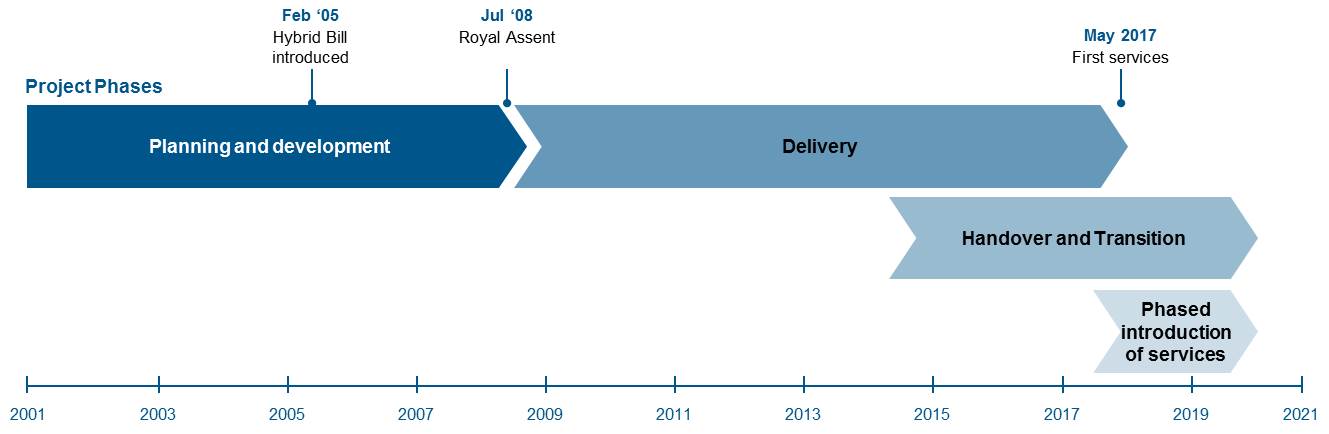

Figure 1 – Phases of the Crossrail Project

3. Context

Crossrail Project overview

Crossrail is Europe’s largest construction project with over 10,000 people working across more than 40 construction sites. It will transform rail transport in London and the South East, increasing central London rail capacity by 10%, supporting regeneration and cutting journey times across the city. The route will run over 100km from Reading and Heathrow in the west, through new tunnels under central London to Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the East. There will be 40 stations including 10 new stations which will bring an extra 1.5 million people to within 45 minutes of central London and will link London’s key employment, leisure and business districts; Heathrow, West End, the City, Docklands; enabling further economic development. The first services through central London will start in late 2018 transporting an estimated 200 million passengers per annum. Construction of the new railway will support regeneration across the capital and add an estimated £42bn to the economy of the UK. The total funding envelope available is £14.8bn, underwritten by DfT and TfL, with contributions from Network Rail, BAA (now Heathrow Airport Limited), City of London Corporation, Canary Wharf Group, and Berkeley Homes.

History of the Crossrail Project

The project has its origins in the Central London Rail Study (1989); that ultimately led to London Underground and British Rail Network SouthEast jointly promoting a private Bill in 1991. The private Bill failed in 1994 but the project was maintained by a small team in London Underground, who were responsible for safeguarding the route. An east-west link was included in the Government’s ten year transport strategy in 2000, which led to the preparation of the business case for the project.

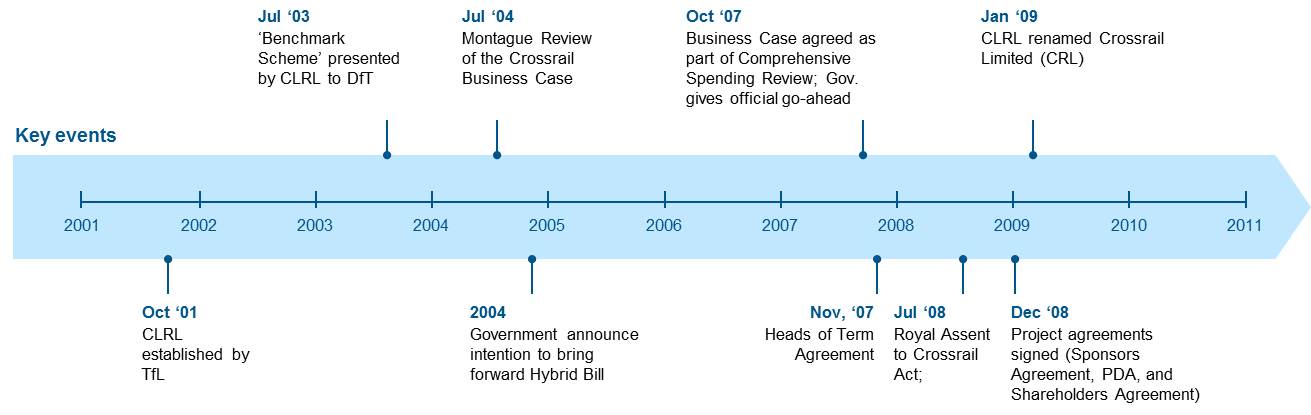

Figure 2 – Timeline of Key Events

Cross London Rail Links Limited (CLRL) was established in 2001 and charged with developing Crossrail to the point that an application for powers could be made. CLRL was jointly owned by the Strategic Rail Authority (SRA) and TfL. CLRL became a wholly owned subsidiary of TfL in December 2008 and changed its name to Crossrail Limited (CRL) in January 2009.

In establishing the business case, there was concern that the traditional Treasury Green Book approach to business case methodology underestimated scheme benefits, and serious efforts were made to make it reflect the wider economic benefits. CLRL also looked at risk and contingency and presented what was termed a ‘benchmark scheme’ to the Department for Transport (DfT) in 2003. The Government commissioned review of the business case, by Sir Adrian Montague in 2004 reported favourably and later that year the then Secretary of State for Transport, Alistair Darling, announced the Government’s intention to bring forward a hybrid Bill seeking powers to deliver the scheme and to consult on funding arrangements.

In 2005 the business case, on which the funding package was developed, was published and subsequently agreed as part of the 2007 Comprehensive Spending Review. The scheme’s go-ahead was officially announced in October 2007 by the then Prime Minister Gordon Brown. Royal Assent established the Crossrail Act in 2008. The CLRL team supported by sponsors and Infrastructure UK (IUK) developed the governance model for the project. In developing the model, the team drew from precedents of other large infrastructure projects as a basis for evaluating the benefits of various models: Robert Jennings, representing HMT, brought experience from the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL now HS1), a PPP (public-private partnership) project; James Stewart as Chief Executive of IUK brought cross-government experience of large infrastructure projects including the Olympic Delivery Authority; Mike Fuhr as DfT SRO for the project brought DfT’s experience as sponsor of rail projects including CTRL; and Martin Buck as CLRL Commercial Director brought experience of cross-sector SPVs and PPPs. The team developed a public authority company structure, with CRL established as a public sector SPV-style company accountable to an independent Board, as the preferable model. The key relationship between the sponsors as customers, and CRL as the delivery body, was set out in a Project Development Agreement (PDA) – in the form of a quasi-private sector arms-length agreement. CRL was also appointed as the principal “nominated undertaker” pursuant to the Crossrail Act.

4. The Crossrail Solution

a. Sponsor and stakeholder integration

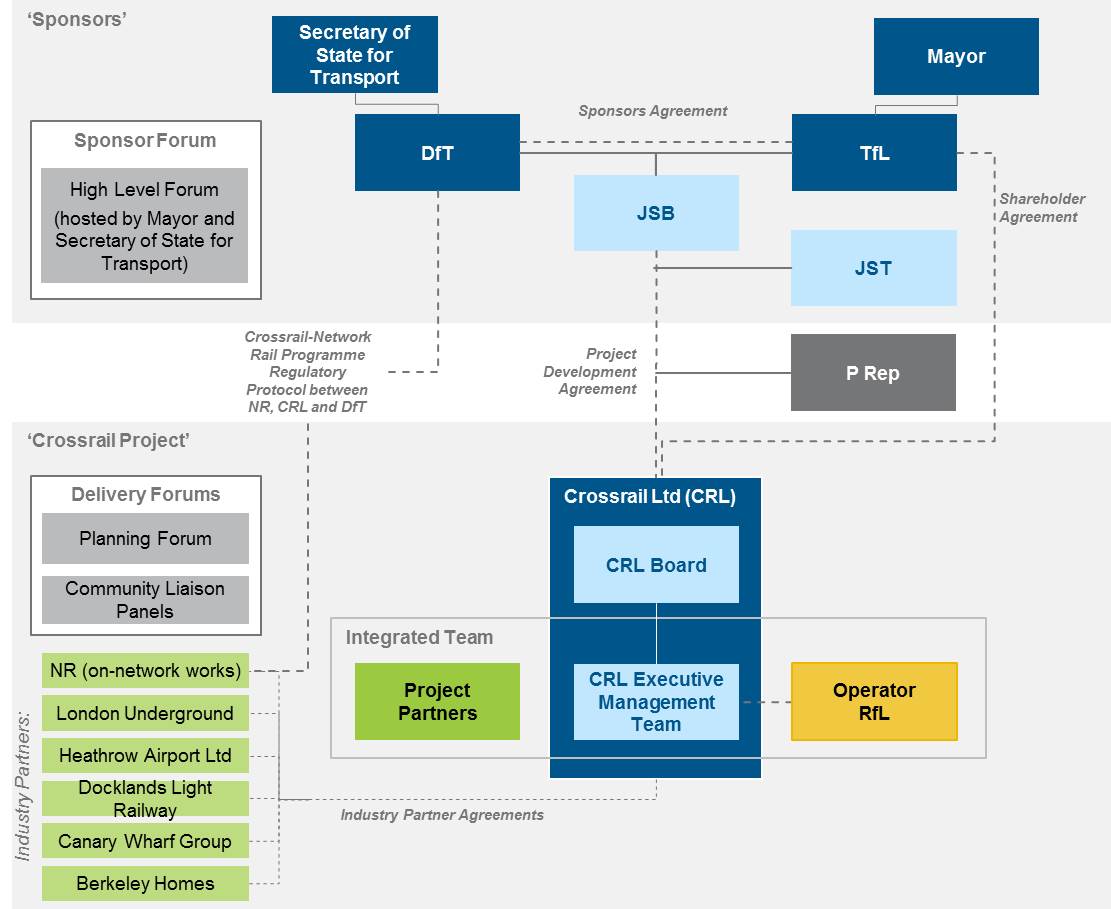

From the outset the scale and geographical extent of Crossrail dictated that it would require a high degree of collaboration between central government (HMT and DfT), London government (the Mayor/GLA/TfL) and Local government (London Boroughs and the City of London), and would involve a large and diverse community of stakeholders. Accordingly much of the initial work to develop and bring forward the scheme had been funded and undertaken as a joint effort between the DfT (initially through its agency, the SRA) and TfL. At the same time, with a project duration in excess of 15 years, it was clear that the interests and priorities of many of the above parties might well change over that time and the project structure would need to be resilient to that changing environment.

i. Integration of Joint Sponsors

The sponsor or “customer” or “client” is the organisation or organisations that are accountable for making the case for investment, securing funding, specifying the project’s outputs and ensuring that the project benefits are delivered. The sponsor is also responsible for defining the constraints (principally the timescale and funding envelope) within which the project is to be delivered.

Whereas the original design envisaged the project would have a single sponsor, TfL, it was decided in 2007 that additional DfT sponsorship would be appropriate. The rationale for DfT’s sponsorship reflected the provision of central government funding through DfT and the requirement to ensure DfT outcomes were balanced in harmony to those of the local government in London. In this instance, DfT sponsorship ensured that central government would have sufficient influence on the project objectives, outcomes and oversight of delivery.

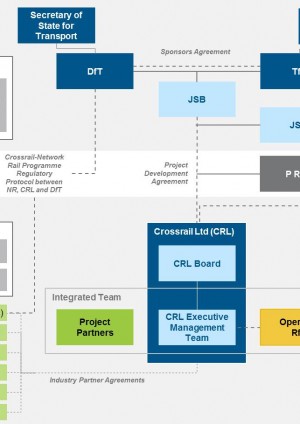

The initial starting point in aligning sponsor arrangements was the negotiation in 2007 of the Heads of Terms to record agreement in principle between both sponsors. The interests of the two sponsors were then brought together through a Sponsors Agreement which was negotiated and agreed in 2008. It sets out the overall management, ownership and governance of the project, including the roles and responsibilities of each sponsor and risks to be managed by each. For the delivery phase of Crossrail, the sponsors (TfL/DfT) established a governing body in the form of a Joint Sponsor Board (JSB, now referred to as Crossrail Sponsor Board), comprising two members from each of the two principal funding bodies. The Chair is rotated on an annual basis amongst the members, with the principal representatives of DfT and TfL being the Director General of the Rail Executive (now referred to as Rail Group) and Managing Director Finance respectively. The JSB was initially supported by a Non-Executive Director (the then CEO of Partnerships UK) charged with supporting the smooth operation of the Board and being an independent voice.

Fully developed Sponsors Requirements were agreed and enshrined in the Project Development Agreement (PDA) in 2008. The sponsors reserve the right to change scope without the provision of additional funding, with any change to those requirements subject to control by the sponsors acting jointly. In addition, the sponsors are obliged to each other and CRL, to meet their respective funding commitments for the entire programme. The JSB maintains an executive function, the Joint Sponsor Team (JST), to provide the day-to-day point of contact for CRL. The JST has responsibility for supporting the sponsors through the provision of management information on project performance and coordinating independent assurance from the Project Representative (P Rep). The Head of the JST, and the P Rep also attend the JSB.

The matters reserved to the sponsors include approval of the appointment of the CRL Chair, Chief Executive, and the Non-executive Directors, and any amendment or waiver to the PDA or Sponsors Requirements.

ii. Integration of wider stakeholders

The Treasury’s position was that it was only prepared to fund Crossrail in the same proportion that London contributed to the wider UK economy, and the potential economic benefits accruing to London itself had to be paid for by the beneficiaries. This position drove the requirement for the project to secure the support of the London business community and Local Authorities ahead of the business case being approved.

The Montague Review of the Crossrail business case in 2004 suggested there was broad consensus among the business community that it was prepared to pay its share. Following this, significant engagement with the business community was undertaken by TfL in the period 2005-2007 to secure support and financial contribution for the project on the basis of what was perceived as a credible business case. Similarly the Mayor of London supported the integration of Local Authority support through both prioritising Crossrail over other schemes and leading efforts to secure support from across London’s Local Authorities.

Following Royal Assent to the Crossrail Act in 2008, the responsibility for working-level integration of wider stakeholders has largely been assigned to CRL, with limited involvement by either sponsor; however, while CRL relies on the support of its industry partners and wider stakeholders, neither group has any ownership or control over CRL in the same way that DfT and TfL do as sponsors. Instead their influence is exerted through various forums and non-contractual boards. For instance, significant stakeholders are invited to a High Level Forum, hosted by the Mayor and Secretary of State for Transport on a rotating annual basis. In addition, the Crossrail Programme Director chaired a Programme Board attended by Industry Partners (Network Rail, London Underground, Docklands Light Railway, Canary Wharf Group, Berkeley Homes and Heathrow Airport Ltd), which provides a non-contractual forum for coordination and issue resolution. The Programme Board was replaced by the Railway and Systems & Operations Programme Board, with a smaller number of industry partners. Other stakeholder panels include the Planning Forum and Community Liaison Panels. The Executive Team has been particularly proactive in ensuring that they are available for individual discussions with wider stakeholders should they have any concerns or queries.

Network Rail is involved in the project in a number of ways, including: being contracted to deliver the surface infrastructure and providing the associated funding (£2.3bn); being the infrastructure manager for a large part of the railway once operational; being the system operator for the UK rail network. Network Rail is currently engaged in Crossrail as an Industry Partner, under a bespoke agreement known as the Regulatory Protocol (2009). Consequently, Network Rail is not represented either at sponsor or CRL Board level; however, Network Rail’s CEO periodically attends the CRL Board. Under the Protocol, Network Rail’s risk exposure is capped at approximately £100m through a pain share with an equal limit on gain share, but with no exposure to the consequential impacts that Network Rail performance may have on the delivery of the central section.

Figure 3 – Crossrail Structure and Governance Agreements

b. Delivery Structure

i. Separation of Delivery organisation from the Sponsors

An important distinction within the Crossrail project is between the sponsor organisations, as described above, and the delivery body – in this case between TfL/DfT and CRL. Confidence in the delivery structure was a key criteria in the decision to give the go ahead for the project. Concerns were raised on dual control/governance of the delivery and a key part of the solution was the separation between sponsor organisations and the delivery body and the “independence” of the delivery body. In these circumstances, it was also important that the sponsors were able to talk with a single voice (through the JSB) when acting as counterparty to the agreement with the delivery body. The structure, combined with the project agreements (see later section below) was created to maintain clarity of accountabilities and provides the delivery body with autonomy to focus on delivery in line with Sponsors Requirements.

The delivery body is the organisation responsible for ensuring the project is delivered as per the Sponsors Requirements in the PDA. Its role is defined in the project agreements as the manager and implementer of the Crossrail project, which in turn is defined as the development, design, procurement, construction, commissioning, integration and completion of a railway system capable of operating the specified services. The clear separation was created to enable the delivery body to have a single focus on delivery of the project as specified, and be unencumbered by the potential change in sponsor priorities over the duration of the project.

Following its appointment as the delivery body, CRL has been established as a wholly public-sector owned SPV delivery vehicle (modelled on a private sector Private Finance Initiative (PFI) or Public-Private Partnership (PPP) SPV), incorporated under the Companies Act with a level of governance generally commensurate with the Combined Code for listed companies. The rationale for creating a discrete independent company was to enable private sector commercial focus, leverage standards of practice and attract the necessary skills and expertise. It was set up purely for the purpose of building the project overseen by its own management team, and an independent board of directors which leads the company on a day-to-day basis. The Executive Team report to the CRL Board, not to TfL, and the CRL Board is accountable to the sponsors. Therefore CRL has a significant degree of autonomy and is not subject to day-by-day oversight from its sole shareholder, TfL.

ii. The composition and role of the CRL Board

The Board is led by an independent Chairman, recruited by an open and competitive process, against appropriate terms of reference to include sufficient knowledge and understanding of both the objectives of the project and the specific circumstances and risks of the environment within which it will be delivered. The appointment of the Chairman is one of the specified matters reserved to the sponsors.

The composition of the Board is mandated by the Sponsors Agreement, which requires a majority of Non-Executive Directors (NEDs). A minimum of five NEDs (including the Chairman) is required. In addition DfT and TfL may each appoint one NED, these appointments were not initially made but were added to help communication and transparency. Three Executive Directors are stipulated: the Chief Executive Officer, Programme Director and Finance Director. All directors are subject to the normal statutory duties under the Companies Act, including the duties to promote the success of the company and to exercise independent judgment. The appointment and removal of Non-executive directors (other than the two nominee directors) are subject to the sponsors’ dual key control – unless anticipated project costs exceed a threshold (aka Intervention Point 1) set out in the PDA, which gives TfL the right to remove and replace the Board.

The Board’s responsibilities are to oversee the performance of the project delivery under the terms of the PDA, within the funding envelope and in accordance with the governance regime approved by the Board. In turn, the CEO and Executive management are held accountable by the Board for the performance of CRL against its obligations. Key elements of independence, as defined within the project agreements include that the Board:

- has clearly defined objectives and is, in turn, able to both incentivise and hold to account the CRL Executive Team for the achievement of those objectives.

- is able to challenge anticipated intervention by sponsors to ensure that decisions which affect the ability of CRL to deliver against the requirements are fully understood.

- is focused on the management of risk, in particular the risk that the TfL contingent funding may be drawn upon. Consequently, CRL’s risk management processes are central to its business and have been instrumental in controlling cost.

- is able to proceed in the knowledge that the project funding is committed to a very high level of probability (P95).

There is a high level of transparency and disclosure under the Crossrail governance arrangements. In line with this, the Board has required the CRL Executive Team to provide comprehensive reports every four weeks, in order to demonstrate performance against its objectives. In addition, CRL is contractually obliged under the PDA to provide a “Construction Report” and every six months a comprehensive progress report and forecast to the sponsors. Those four-weekly and six monthly reports are scrutinised by the P Rep and the JST and provide a high degree of visibility to the sponsors.

Both the CRL Board members and the Executive Team were selected on their experience of delivering major infrastructure projects and track record in organising and managing the project and attendant risks. One of the key roles of the Board in leveraging this experience was to provide challenge back to the sponsors to ensure their actions did not compromise delivery of the project.

iii. Ownership of CRL and the Shareholders Agreement

CLRL was originally tasked with the development of the scheme in its early stage. Following the passing of the Crossrail Act in 2008, CLRL was renamed CRL and became a wholly owned subsidiary of TfL’s trading arm (Transport Trading Ltd). It was common ground that a continuation of the 50/50 joint ownership structure would have been impractical. That view was grounded in the Montague Review of the Crossrail Business Case in 2004, which concluded:

‘CLRL’s present corporate structure, involving a deadlocked joint venture between the Strategic Rail Authority and Transport for London, would not offer effective project governance going forward. CLRL would also need to do some internal restructuring to take on the role of robust project client’

DfT agreed to transfer its 50% share of CRL to TfL on the basis that the governance arrangements would ensure that CRL would enjoy a high degree of autonomy under the direction of a Board comprising a majority of Non-executive Directors. As described above, other conditions were included in the PDA to ensure CRL had joint accountability to both sponsors. Through the Sponsors Agreement, DfT ensured that it retained dual control over the constitution of CRL, the composition of its Board and the rights of TfL as sole shareholder.

More generally, factors which were considered on the decision around ownership of the SPV included:

- The extent of control required by funders and their governance requirements

- The covenant necessary for the SPV to act as counter-party to the supply chain contracts; including the identity of the provider of the necessary financial support commitment or guarantee

- Tax; in particular the need to be able to ensure benign tax treatment in relation to capital allowances on assets, SDLT on land acquisition and VAT

- The interface with the London Underground network.

Being a subsidiary of TfL afforded the SPV a number of freedoms that enabled it to focus on project delivery whilst having a strong and reputable parent whose objectives and mission align. As a result of TfL’s classification as a local government body, CRL has the freedom to incentivise the Executive Team for achieving targets and is also able to hold cash in bank accounts, giving it operational flexibility to utilise the agreed funding when it feels it is most appropriate. In contrast, HS2 Ltd, a Non-Departmental Public Body owned by central government (through DfT) currently has neither of these freedoms. It is also arguable that CRL’s status as a wholly owned subsidiary of TfL means that TfL carries a greater reputational risk if CRL is perceived to have not delivered and therefore the organisation is heavily incentivised to assist CRL to the greatest extent possible.

c. Governance Arrangements

i. The Project Development Agreement (PDA)

The PDA created arrangements analogous to a Project Agreement between a private-sector SPV and a sponsor on a PFI/PPP project, clearly defining the role of the sponsors, CRL and the operators, albeit with CRL as a public sector SPV and with HMT /sponsors taking both funding and equity risk. The PDA defines the sponsors as the owners of the business case, with accountability for specifying the project outcomes and taking the funding risk. CRL is the delivery agent accountable for designing and delivering the infrastructure, within funding limits, in accordance with a specified timescale and taking delivery risk. Rail for London (RfL) and London Underground Limited (both subsidiaries of TfL) are defined as the parties accountable for the operation and maintenance of the infrastructure, and ultimately for realisation of the benefits forecast in the business case. The PDA originally envisaged Network Rail as the infrastructure manager for the central section but that role was transferred to RfL in 2012 (see below).

The PDA formally records the agreement between the sponsors and CRL. It was drafted and negotiated with the assistance of specialist project lawyers, with each party being separately represented. It includes a number of terms which were designed to provide the sponsors with confidence over what was being procured.

Crossrail Project Development Agreement includes definition of: - The scope and specification of the project (the ‘Sponsors Requirements’)

- The principles by which CRL will deliver the Sponsors Requirements (the ‘Functional Response’)

- The roles and responsibilities of the parties and how they will interact

- Funding envelopes and spending rules

- The content and form of Management Information required by the Sponsors

- The systems and processes which will need to be in place and by when

- Intervention points and step-in rights

Table 1 – Crossrail Project Development Agreement Overview

The PDA also set out the freedoms which CRL needed to deliver the project in a cost effective way, including:

- The justification and approach to how changes in delegations would be made to CRL to empower it to make commercial decisions in a timely manner in the best overall economic interest of the project

- A defined process to support timely decision making between sponsors and CRL to avoid delay to the project

- A defined process for both sponsor initiated and CRL initiated change to enable consideration of the impact of change prior to decisions / implementation

- Certainty around the provision of funding and the approach to procurement and execution to provide confidence to the supply chain and reduce risk pricing.

The PDA is not a legally enforceable contract. Any dispute between CRL and TfL or any other TfL subsidiary would be subject to determination by the TfL Commissioner. Any other dispute arising from the PDA would be subject to determination by the sponsors in accordance with the Sponsors Agreement (which is a legally enforceable contract).

ii. Earned Autonomy and the Review Point Process

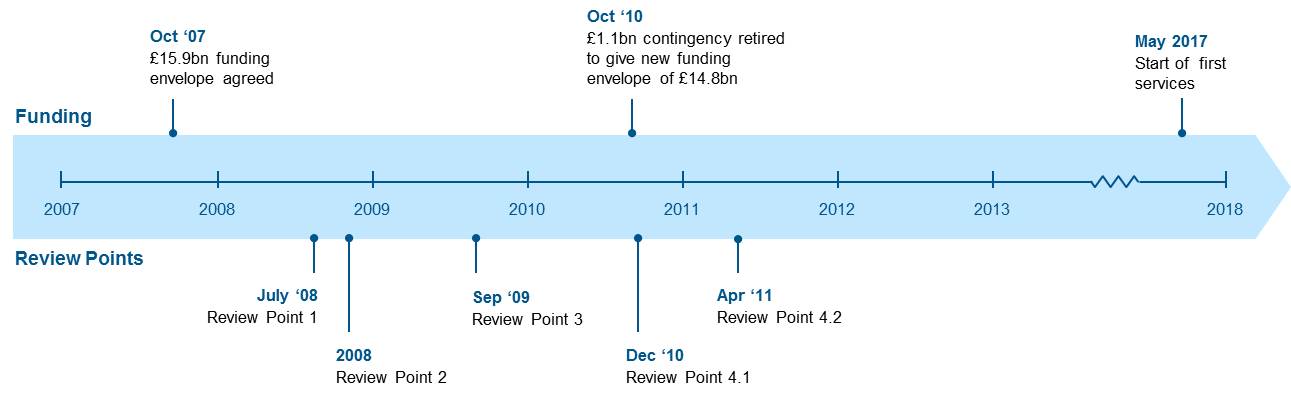

A key element of the PDA was the approach by which the required autonomy was granted to CRL. This reflected the acknowledgement of the increasing need for effective and timely decision making as the project entered implementation, when the impact of delay and change would become more costly. Therefore, as the project progressed from the planning to the delivery phase and confidence in the delivery plan and cost outcomes grew, the principle of earned autonomy was used in order to gradually transfer responsibility and decision making authority to CRL. Increased delegation was granted over a three year period through a structured review point process. There were 4 Review Points, with the final Review Point 4 split into two parts to support CRL letting time-critical contracts in December 2010 before meeting all requirements of Review Point 4 in April 2011.

Figure 4 – Funding and Review Points timeline

Review Point Overview RP 1 CRL formed in July 2008 on the passing of the Crossrail Act RP 2 Core project documents signed in 2008 RP 3 Interim review of project, cost and delivery strategy RP 4.1 Permission granted to award the four contracts for tunnelling work in the central section RP 4.2 Full transfer of operational powers to TfL Table 2 – Programme Development Agreement Review Points

At each Review Point after the signature of the PDA, the capability of both the sponsors and the delivery body (CRL) was assessed internally, utilising the newly formed Major Projects Review Group (MPRG) within HM Treasury. The most important review points were 3 and 4, where freedoms granted following each Review Point were:

- After Review Point 3, CRL had the freedom to issue tender notices in relation to its major procurement contracts

- After Review Point 4.1, CRL had authority to award delivery contracts.

- After Review Point 4.2, CRL had full operational powers including tendering contracts and managing contingency.

iii. Intervention points and Incentivisation of the delivery body

A key element of the incentivisation arrangements was TfL holding the first tranche of sponsors’ contingency, to be used if CRL exhausted its own delegated contingency. This incentivised TfL to focus on managing its own retained risks, including the interface with LU and RfL.

Incentivisation of CRL to deliver the Sponsors Requirements within funding and time constraints was achieved through the following measures:

- Personal incentivisation of Executive management to deliver to identified KPIs

- Consequences of breaching intervention points linked to the use of contingency (see below)

- Reputation of CRL Board and Management

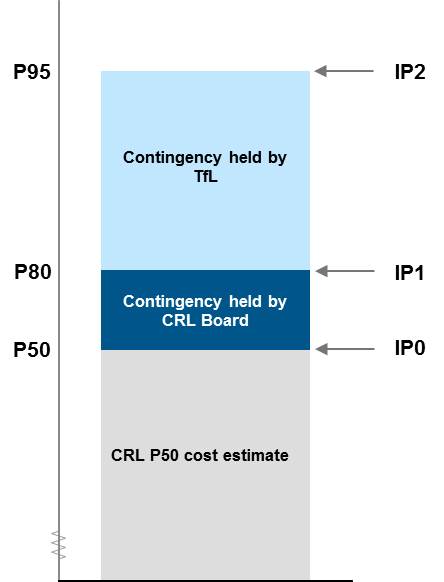

The funding structure for CRL includes the Anticipated Final Crossrail Direct Cost (AFCDC) of £12.5bn (Total funding of £14.8bn less Network Rail contribution of £2.3bn), defined as the P50 cost estimate (the cost estimate where there is 50% probability of delivering the project), delegated contingency funding up to the P80 cost estimate to CRL, contingency between P80 and P95 held by TfL, and DfT responsible beyond P95.

The sponsors have a series of intervention points at which they can take action if the project is forecast to cost more than the AFCDC. These clear intervention points have provided a focus on active programme and cost management whilst providing CRL with the freedom to manage risk. A crucial part of the structure is a sequential right of ‘step-in’ by the sponsors, namely that TfL could step in first, if the contingency held by it was required and then DfT could step in once TfL contingency had been exhausted. This approach allowed single decision making at potential crisis points rather than joint sponsor decision making which may have led to delays or even non-decision.

Figure 5 – Intervention Points – as at 9 January 2016

- The first Sponsor Intervention Point (IP0) occurs if the forecast out-turn cost is greater than the P50 cost estimate. At this point, CRL may be requested to submit remediation plans to TfL showing how it would ensure the project is delivered for the Target Cost.

- At the second intervention point (IP1) defined as the P80 level, and only once it is clear that an element of the contingency held by TfL will be required, TfL are able to step in and replace Directors and senior Executives, taking more responsibility for the project.

- At the third intervention point (IP2), if the TfL contingency fund is exhausted, DfT can intervene, or TfL can hand the project to DfT.

5. Lessons learned

Sponsor and stakeholder integration

i. Integration of Joint Sponsors through a formal agreement and governance, early in the project is essential to ensure alignment and a single interface between the Sponsors and the delivery body

Where major projects have more than one sponsor, at an early stage in the project, the sponsors need to determine how their respective requirements will be reconciled, how their interests (including retained risks) will be represented and how the risk of decision making deadlock and delay can be avoided. On Crossrail, these issues were dealt with in the Sponsors Agreement and the formation of the Joint Sponsor Board. Combining the two sponsoring authorities under a joint legally enforceable agreement and through an executive function (the Joint Sponsor Team) has proved effective in this regard. It could be argued that earlier sponsor agreement may have shortened timescales between the initial business case in 2003 and its final agreement in 2007. Once sponsorship was agreed, the time and effort developing a robust Sponsor Agreement, in parallel with other project agreements, was a worthwhile investment as this has reduced instances of conflict through providing clarity of governance and formed a key part in securing support from HM Treasury.

“The focus on defining the role and responsibilities of the parties as captured in the project agreements was time well spent, as this has provided real clarity in how the project has been governed and enabled the sponsors and CRL to focus on the key issues and risks”

David Hughes, Director of Crossrail Joint Sponsor Team, Transport for London (2008-2013)

ii. Effective Joint sponsorship has contributed to controlling project scope; with the project agreements enabling provision of valuable challenge where one sponsor has sought scope change

The risk of unfunded scope change by sponsors is one of the risks which the Crossrail governance arrangements have sought to address. Whilst this risk was left open in the PDA (see later point), this has been mitigated to some extent by other measures. The requirement, as set out in the project agreements, for scope change to be agreed jointly by sponsors and the focus of each sponsor in securing its own project outcomes and in managing its own retained risks has helped control scope change. Where one sponsor has, on occasion, sought to introduce scope change the other has provided valuable challenge; the result of which has been to reduce the amount of change which has been absorbed by the project.

“The sponsorship model worked extremely well: having two sponsors allowed each to hold the other in check against differing priorities; and the PDA and other project agreements gave great clarity on the respective roles of the sponsors and Crossrail Limited”

Steve Allen, Managing Director Finance, TfL and Lead TfL Sponsor (2008-2015)

iii. Independent Non-Executive advice to the Joint Sponsor Board supported effective operation and appropriate focus of the Sponsors

The smooth operation and adherence to governance by the JSB’s predecessor (the Pre-agreement Sponsor Board) and subsequently the JSB was supported by the Non-Executive Director (Chief Executive of Partnerships UK). This support was valuable to enhance the understanding of how sponsor nominees should discharge their sponsor responsibilities in relation to a major capital programme delivered by a separate delivery organisation. In this instance, this has been achieved through the Non-Executive Director being a neutral voice and supporting and providing challenge to the DfT and TfL Board members both when the Board sits and ‘off-line’. Once the JSB had established its operation, the requirement for this role lessened and was eventually removed.

“Dual sponsorship by DfT and TfL of Crossrail meant that robust governance for the programme was essential, and the arrangements put in place have worked well. Formalising the role and responsibilities of the sponsors and CRL through the project agreements has been helpful in providing a robust framework to enable the sponsors to speak with ‘one voice’ and in providing clarity of CRL’s delegated authority to manage delivery of the programme”

Claire Moriarty, Director General Rail Executive and Lead DfT Sponsor (2013-2015)

iv. Close integration of stakeholders supported approval of the business case, but in future projects more formal integration would be appropriate if the business case is reliant on the realisation of wider benefits

Support from the business community and Greater London Authority was a key factor in securing approval of the business case. This required a robust and sustained period of engagement by TfL which ultimately led to stakeholders supporting the scheme through the commitment of direct and indirect funding, which was in addition to the core funding provided by DfT and TfL. Both stakeholders’ (which provided funding) and Local Authorities’ ongoing influence has been exerted through various forums and non-contractual boards, and their confidence in CRL’s ability to deliver has been supported by the appointment of independent NEDs.

Arrangements for future projects, might benefit from considering more formal integration of stakeholders who provide funding to the project, to ensure their interests are protected. In this case, integration of these would be best achieved through integration at sponsor level to ensure there is alignment of objectives and to enable the delivery body to focus on implementation.

Similarly when considering future projects, more formal arrangements might be required if the business case and funding from central government was based on the delivery of wider benefits (e.g. regeneration or economic growth) outside of the direct control of the delivery organisation. In this instance, it is likely that the owners of the business case (the sponsors) would need to ‘strike deals’ with each of the stakeholders which are accountable for delivery of the benefits. These arrangements would need to be formalised at the sponsor level to retain the ability to have one set of sponsor requirements communicated through a single Sponsor Board. This would ensure clarity of objectives and enable the delivery body to focus on implementation.

v. Integration of Local Authority stakeholders through the project development and delivery phases has supported delivery to schedule, specifically through early engagement to shape the project

Whereas the Crossrail Act provided the delivery body with powers (e.g. land access, compulsory purchase), in practice careful management of the interaction with Local Authorities was required to ensure that planning related permissions were secured in time to support the delivery schedule. Involving Local Authorities in the formative phases was important in allowing them to have a role in shaping the project and to reduce the risk of delay during project delivery. However, the powers secured through the parliamentary process do have limitations in their ability to provide certainty to the delivery organisation (in general terms powers granted are based on outline planning permission) with detailed or full planning permission still needing to be secured from Local Authorities following Royal Assent. In practice, CRL managed this risk through on-going engagement at three levels; face-to-face interaction with leaders of Local Authorities, customer-focused local area teams to deal with complaints from residents, as well as working with local planning officers.

When considering future projects an alternative approach to alignment of LAs objectives with those of the project, to reduce the risk to cost and schedule creep, would need to more formally secure LAs support earlier in the process and potentially include harnessing the GLA’s (or similar) support and special powers.

An area identified as having the potential to reduce the burden on the public purse, was a more ambitious approach to redevelopment of stations. This concept could have involved additional over site development and potentially the use of private sector capital but would have been reliant on different powers in relation to compulsory purchase. The implications of this approach on structure and governance could (as above) include the need for deals to be made at sponsor level to provide clarity and certainty around the support required from Local Authorities in return for securing the redevelopment benefits (e.g. support for planning permission for more ambitious redevelopment). This clarity would be most effectively secured early in the project life-cycle and ahead of the deposit of the Hybrid Bill (at which point petitioner perspectives on the plans would need to be sought).

vi. Closer integration of Network Rail may have enabled greater risk transfer but on balance its role as a delivery body under CRL’s programme management has proved effective

Network Rail was initially assumed to be the infrastructure manager for the central section and was consequentially involved in the pre-agreement discussions. Ultimately, this did not happen and it was engaged relatively late in the development of the scheme, in part a function of the failure of Railtrack in 2002 and in part due to the lack of a clear strategy for their engagement. It could be argued that late involvement allowed Network Rail to adopt a relatively risk free stance and that inviting Network Rail to take an equity role, at an earlier stage, was an opportunity missed. However it should be noted that whilst there is limited financial risk transferred to Network Rail, there is significant reputational risk involved in the delivery of such a high-profile project. Future projects, which have a similar interface between the delivery body and Network Rail or other similar bodies should consider how objectives between the two organisations can be aligned and appropriate risk sharing can be reached e.g. through a Joint Venture or equity participation in the delivery body.

On balance, because of Network Rail’s other priorities and constraints on funding (which would have required regulatory approval), it had limited locus on the business case. Ultimately its position as a complementary delivery body under CRL’s programme management, where it is required to meet obligations under the ‘track access option’ with CRL managing the interfaces has provided clarity of its role and delivered a workable solution. Network Rail’s regulatory model, which did apply to its role providing the surface infrastructure, contributed to limiting the ability of CRL to secure a higher degree of risk transfer; however, this risk has been managed effectively through close interaction with Network Rail both at Board level and at the working level.

Delivery Structure

vii. Separation of the delivery organisation from the sponsors has provided clarity of responsibilities and maintained the focus of each party, and enabled delivery of project objectives to time and cost

Crossrail formed a clear split between the SPV (CRL) and the sponsors (DfT and TfL). The separation of customer/sponsor and deliverer roles has maintained clear accountability for setting requirements and provision of funding, and delivering the project objectives within time and cost parameters. It has allowed the right skills to be put in the appropriate place, e.g. public policy and “client” skills in the JSB and private sector delivery skills in CRL. It has also enabled the ring-fencing of CRL’s budget to protect the project from subsequent potential change to funding associated with a government funded project. To support effective operation of the JSB and its interaction with CRL, continuity of sponsor representatives is helpful, especially in providing a consistent approach to sponsorship.

viii. Establishing the delivery vehicle in the form of a publicly owned Limited Company has proved effective and resilient, by bringing a level of discipline comparable to a private sector style SPV

Companies and government agencies have established organisations and governance processes appropriate to the scale and complexity of projects that they normally manage. When faced with a project of unusual scale or complexity or that involves sharing risk with another party it is commonplace for enhanced arrangements to be required. Those arrangements might include adding to the company’s existing capability, entering into an alliance with parties who share the project’s objectives or establishing an SPV, as was the case for Crossrail.

Creating CRL as a “private sector style” SPV has brought a level of discipline comparable to an SPV on a PFI/PPP project. The standards of practice and governance are defined by law or industry best practice.

ix. The independence afforded to the delivery vehicle has supported it to attract high calibre talent, with the necessary experience and skills to manage a project of this scale and complexity

Although the appointment of the Chair, the independent Non-executive directors and the Chief Executive are all subject to the approval of the sponsors, and each sponsor is entitled to nominate a non-executive director, each director once appointed has a statutory duty to act in accordance with the best interests of CRL (and hence the project). Board members have acted accordingly and extended parties have respected that independence. This independence was a key factor in attracting a Chairman, Board and Executive team which had the necessary experience and skills to manage a project of this scale and complexity.

“Central to the positive achievement to date of the huge Crossrail project has been the independent nature of its Board structure – providing expert delivery under freedom of operational decision-taking against a backdrop of regular and rigorous reporting and review with the stakeholders.”

Michael Cassidy CBE, Non-Executive Director CRL (2008-ongoing)

The independence afforded to the Board has provided space for CRL to develop and manage a set of relationships with its stakeholders and the public at large to meet the requirements and particular circumstances of the project at each phase. This independence of relationship has in large part also insulated the sponsors from the risks associated with the delivery of the project.

x. The constitution of the delivery company as an SPV outside of the normal controls associated with the public sector, enabled a high calibre executive team to develop, organise and manage the resources required to achieve the objectives of the project

Whereas the ownership classification of CRL as a local government owned body has provided some freedoms around pay, incentivisation and ability to hold cash in bank accounts, the primary value in the structure has been its ability to create a focused team with a clear identity and culture.

The project team was free to develop the culture, values, systems and processes specifically to meet the needs of the project. The identity and strength of the Crossrail ‘brand’, its ‘private sector’ disciplines and public sector ethos has fostered a sense of pride in the organisation and the focus on delivery of its task.

xi. Timing of formation and ownership of the SPV should be focused on the requirements of the project, as the creation of an SPV is beneficial to facilitate procurement, management and promotion of the project

The point at which ownership and control become key factors should determine the point at which the SPV should be created and when clarity of ownership is required. The creation of an SPV is beneficial to facilitate the procurement, management and promotion of the project; however, during the development phase the covenant required to support the supply chain contracts is very modest. Therefore, the precise nature of ownership and control of an SPV at an early stage is less critical, provided the arrangements put in place are conducive to the development of a scheme which can command political support at all levels.

In Crossrail’s case, the SPV was established as CLRL early in the project lifecycle and ahead of business case approval, which enabled the 50/50 ownership by the SRA and TfL to be accommodated. The Crossrail experience has demonstrated that where a project has dual sponsorship, 50/50 ownership is not an impediment in the early stages of development of the project but it is not the optimal solution for the delivery phase. Crossrail has demonstrated that the governance arrangements it has developed have provided a better alternative for aligning the sponsor interests. Having clarity around the form and ownership of the SPV should ideally precede with the negotiation of the project agreements and at the latest be in place to support implementation thereafter.

xii. Securing the Chairman and CEO at an earlier point may have provided a more robust basis for the initial stages of implementation

As the project has evolved, the roles of the Chairman and CEO of CRL have changed, particularly as the project moved from the development phase (ahead of the Crossrail Act in 2008) to the construction phase. The skills required to pilot a project through business case approvals and to secure political support are different to the skills required to deliver a nationally significant project on the scale of Crossrail. HM Treasury and the sponsors would not have delegated authority at each of the Review Points, particularly Review Point 4, without confidence in a suitably qualified board and management team capable of overseeing the delivery of the project.

“One of the most important aspects was to form a competent Board that could act independently, but still have a representative from each of the sponsors in order to facilitate information flow and demonstrate transparency”

Doug Oakervee CBE, Chairman CLRL (2005-2008)

It proved difficult to attract the Chairman and Executive team ahead of a clear commitment from government to proceed with the project. As a result of this and the existing project implementation plan, the Chairman and Chief Executive were recruited in parallel and at the same time as the procurement of the project Development Partner. An approach which sequentially recruited the Chairman, then the Chief Executive and enabled them to shape the delivery strategy would have provided a more robust basis for delivery of the project and avoided some delay associated with reshaping the delivery strategy and structure of the Development Partner arrangements. From a practical perspective, because there was little room for project schedule delay, this would imply that the recruitment should ideally have happened at an earlier stage.

Separating the role of Chairman and Chief Executive was seen as an important part of satisfying sponsors of the robustness of the governance arrangements and the ability of the Board in holding the executive management team to account. Creating this separation ahead of the transfer of delegated authority was an important part of providing comfort to the sponsors. Additionally having a separate Chair and Chief Executive has proved appropriate for the size and complexity of Crossrail and degree of stakeholder interaction required.

xiii. The experience and composition of the CRL Board has supported the independence of the SPV and secured sponsor comfort in delegating authority to the SPV

Having a high calibre Board has been invaluable in providing challenge to the Executive Team to support successful delivery of the project. The competency of the Board has provided confidence to both the sponsors and other financial contributors such as the City of London. It also provided HM Treasury with confidence that authority could be delegated to CRL.

One aspect of particular importance to providing confidence to the sponsors was the inclusion of an independent representative from each of the sponsors as a Non-executive Director. This arrangement has facilitated information flow and transparency amongst the three organisations. The benefit in selecting the nominee Directors on the basis of their experience has benefited both the operation of the Board in challenging the Executive and the confidence of sponsors in the opinions of the NEDs. Independence of the Board was enhanced by the sponsor nominated NEDs, not being salaried employees who might have competing priorities.

Periodic review of the NEDs has worked effectively to ensure the Board has the right skills to influence the project in its different stages. For example, the primary focus of the Board during the initial stage of the project was on procurement and the delivery approach whereas it is now primarily concerned with challenging delivery performance.“The success of Crossrail has been enhanced by the ability to attract a Board and management team with relevant experience of delivering large and complex infrastructure projects; this has been enabled through the independence and autonomy provided to Crossrail Limited to focus on project delivery”

Terry Morgan CBE, Chairman CRL (2008-ongoing)xiv. Ownership of CRL by TfL, as ultimate owner of the scheme, has supported delivery of the scheme; however, earlier involvement of the operator mind-set might have enhanced whole life solution

TfL as parent and owner of the Crossrail infrastructure has assisted in both the delivery phase and in considering the operational requirements which the infrastructure will need to support. There have been instances during construction when TfL has worked co-operatively, at the detriment to the operational performance of its existing network, to support efficient delivery of the scheme. Arguably this would have been less likely had the relationship between the two parties been more arms-length.

In the period up to the transfer of ownership to TfL, the SPV included an “operator” function; however, this was carved out of the organisation at this point by the sponsors. As a result CRL, by design was created solely to construct the infrastructure. Whereas operations are a fundamental element of the railway, they were excluded from the sponsor requirements on the assumption that they would need to be integrated into the TfL network and therefore TfL was expected to take ownership of the railway at an early stage of the commissioning process. A pure construction focus has the potential for the delivery body to deprioritise considerations relating to the future ownership and operation. CRL has addressed this risk through retaining from the outset a small residual “operator” group (and Operations Director who is a TfL Rail employee) which has expanded considerably after Review Point 4.2. However, there is a case that the operator ‘mindset’ could have been more explicitly set-out in the PDA and clear timescales for handover set out to ensure whole-life considerations were applied at the design stage when maximum influence can be included in the solution design.Governance Arrangements

xv. The Project Development Agreement has provided a robust basis for the governance, assurance arrangements and management of risk between the parties

The PDA with the associated Sponsors Requirements documentation provided a resilient definition of responsibilities and accountabilities. This has enabled the JSB to focus on oversight of the primary risks and issues rather than being distracted as the result of a lack of transparency over roles and responsibilities.

“During the construction phase, the governance arrangements and oversight of the project have ensured tight management of the programme so that delivery to both cost and schedule are well managed.”

NAO Report, January 2014The early and robust evaluation of programme risks by CRL and the sponsors supported the implementation of governance arrangements and enabled effective risk management across the programme. Early consideration of risks ahead of developing the project agreements is essential to identify which risks should be retained by the sponsor and which should be passed to the delivery body and supply chain to manage. For Crossrail, clarity of which interface risks should be retained by the sponsors created clarity and focus for the sponsors and provided the basis for CRL to organise and contract with the supply chain in an effective way.

xvi. The ability of sponsors to change scope without the provision of additional funding could have compromised delivery to time and budget but in practice this risk has been managed effectively

Under the PDA, the sponsors retained the ability to request scope change without providing additional funding. From a sponsor perspective, this was included and has provided a useful mechanism to deal with anticipated areas of ambiguity, where scope which the sponsors had assumed was included had not been priced by CRL. As discussed above, the introduction of scope change is something which, from a project delivery perspective, introduces risk and complexity both with respect to cost and schedule. The later in the project change is introduced the greater the risk and complexity as there is less flexibility to absorb change. In addition the constraints on CRL being unable to lay this off to the supply chain remain as do associated complications with partner agreements (potentially creating misalignment and triggering “reopening” clauses).

“The ability of the sponsors to instruct scope change without providing additional funding could have risked the financial viability of what is a very successful project; from a project delivery perspective there should be careful consideration over whether unfunded sponsor-imposed scope change should be possible and how this should be controlled.”

Robert Jennings CBE, Non-Executive Director CRL (2008-ongoing)Although additional scope has been introduced, the system of dual sponsor challenge within the JSB has limited the extent to which this has been exercised. Without the requirement for joint instruction by both sponsors, CRL may have had many more requests for unfunded scope changes. The role of the CRL Board in challenging anticipated intervention by sponsors is also considered to have exerted a restraining influence. As a result the project scope has remained relatively stable since 2008.

Given the scale and complexity of projects like Crossrail, it is inevitable that there will be some instances of ambiguity which will need to be addressed. In these circumstances the final decision should ultimately lie with the sponsors but a clear approach (included within the PDA) is essential to ensure the scope areas fulfil agreed criteria and that a robust assessment is followed to understand the impact of change on the project. An alternative approach could have been to allocate an element of sponsor held contingency to deal with these eventualities.xvii. Gradual delegation through the Review Point Process has proved an effective way to empower the SPV whilst assuring sponsors of its ability to manage risks

The need for effective and timely decision making increases progressively as the project approaches and enters the implementation phase, when the impact of delay and change will be costly. Critically, the PDA provided for the gradual delegation of authority to the CRL Board over a three year period, subject to CRL demonstrating its capability at a series of Review Points. It should be noted that having the consistency of a suitably experienced management team through this process was an important factor in convincing sponsors to delegate additional authority to the delivery body.

“The governance arrangements for the Crossrail project have provided the freedom for the Executive team to focus on delivering the programme and have supported a successful outcome to date. As the programme enters the commissioning phase and transition to operations, continuity of approach and personnel from both sponsors and CRL will be an important factor to support delivery of the programme at a critical time.”

Andrew Wolstenholme OBE, Chief Executive Officer CRL (2011-ongoing)Although all parties acknowledge the review point process was valuable and worthwhile, and gave comfort to HMT and to the sponsors that CRL was ready to assume ever greater responsibility for the project, it did take up a significant amount of management time and focus. It is helpful for all parties to understand that during the period of transition there was some overlap or duplication in the roles of the SPV Board and Sponsor Board e.g. in the approval of major procurements. Crossrail experience indicates that the time at which performance measures were set also required careful consideration and should be linked to sufficiently mature design and cost estimates. An approach which incorporates gradual delegation of authority requires clarity of roles and approvals (e.g. which decisions are made by sponsors and which by the SPV Board), focused management and should be reflected in the programme plan to ensure there is an efficient process and unnecessary delay is not introduced. It also requires the commitment of all parties to work collaboratively within these constraints.

xviii. The tiered and clear allocation of contingency has supported effective incentivisation; there may have been the opportunity for greater focus on value engineering and out-performing target cost

The incentivisation of the CRL Board and Executive to meet target costs has worked well. The contingency TfL has committed to the project has helped to ensure TfL have supported the project requirements, for example ensuring timely track access. Furthermore, the fact that both the up-side benefit of cost reduction and the down-side risk of overspend was shared with the contractors provided confidence that there was an in-built mechanism to control costs. In retrospect, there may have been benefit in incentivising CRL management to out-perform target costs rather than simply deliver to them.

Whereas value-engineering has been a key feature of the CRL delivery approach (contributing to the £1.1bn reduction in total funding envelope agreed as part of the 2010 Spending Review), in practical terms, incentivisation to out-perform target cost could have provided added focus of management on value-engineering through the life-time of the project. It should be noted there is a fine balance to be struck on the ambition of any incentivisation, in that unrealistic targets are likely to have the opposite effect. It is worth highlighting that the CRL incentivisation to meet target cost must be viewed in the context of previous poor delivery of major projects in the UK and that at the start of the project an outcome to deliver the project on budget was perceived as a good outcome. It should also be acknowledged that the scale, complexity and innovative nature of the Crossrail scheme necessarily implies that it includes significant risk.

Overall the combination of the incentivisation arrangements has created a focus on ensuring the project was delivered to time and budget rather than the lowest cost possible.“Through Crossrail, the UK has pioneered the delivery model which creates clear separation between sponsor and developer. Whilst this has attracted interest internationally, it will be interesting to see if this will be adopted and evolved; for example whether incentivisation aimed primarily at the avoidance of cost overruns can be focused on the delivery of cost savings”

James Stewart, Non-Executive Director Joint Sponsor Board (2008-2011)xix. Independent assurance has provided a critical element in supporting the CRL Board and Sponsors, including the role of the JST in supporting the JSB to discharge its role as Sponsor

Independent assurance has been provided by a number of means and bodies, which combined have supported a robust approach to programme oversight, including the following:

- The role of the JST, in supporting the JSB to discharge its role as sponsor, was a key part of the governance arrangements and one which is considered to have worked well. An important element of its role which has worked effectively has been the interaction with the P Rep, to guide its focus and integrate its advice to provide independent assurance to the sponsors. Given its relatively small size, the effectiveness of the P Rep function is highly dependent on the capability and experience of the individual team members.

- The MPRG reviews as part of the Review Point process have been another key element in providing assurance to the sponsors. These insights brought by the MPRG teams have also assisted and been valued by the CRL Board members.

- CRL has also used the concept of “Expert Panels” to provide independent review of specific issues, through leveraging the experience of a range of international experts. This has provided valuable challenge and support given the highly innovative and in some cases first-of-a-kind approaches used during the construction of Crossrail.

References

- Crossrail Heads of Terms, November 2007

- Crossrail Sponsors Agreement, 2008

- Crossrail Project Development Agreement, 2008

- Crossrail, NAO, January 2014

- Railways: Crossrail 1 and 2, House of Commons Library, July 2014

- Crossrail – Lessons Learned for Initiating Large Public Sector Projects, MPA, 17th February 2011

- Crossrail Governance – Case Study, MPA, Martin Buck, Transition and Strategy Director Crossrail, October 2014

- Crossrail Governance, MPA Course material, Martin Buck, Transition and Strategy Director Crossrail, September 2014

-

Authors

Chris Croft BEng - KPMG

Chris Croft is a Director in KPMG’s Strategy Group focused on the Infrastructure Sector, providing strategic advice for corporates, private sector investors and Government. Chris has led KPMG’s Financial Advice to DfT’s High Speed Rail Group over the last two years which has included support to put in place the HS2 Development Agreement, developing programme funding arrangements and designing and implementing new governance arrangements. Chris also recently led KPMG’s work supporting the NDA assess options for the procurement of the Sellafield decommissioning programme. Chris’ wider experience over the last fifteen years includes: supporting nuclear new build market entrants to the UK; developing new operating model and governance arrangements for a major UK nuclear programme; and evaluating the funding and commercial arrangements within the Maritime defence supply chain. He has also supported strategy and commercial model development for a range of organisations which span the public / private boundary in the infrastructure, energy and defence sectors. Prior to joining KPMG, Chris spent five years in the British Army in the UK and abroad.

Martin Buck FICE FRICS - Crossrail Ltd

Martin was appointed as Transition and Strategy Director at Crossrail in July 2014 after 3 years as Commercial Director. Martin is a member of the Executive and Investment Committee and has responsibility for leading Crossrail’s transition from a standalone project into Transport for London.

Martin is also responsible for procuring the supply chain and third party agreements required to support the Crossrail project.

Martin was previously a project director with Partnerships UK where he managed activities in the transport sector. As a founder member of the Treasury Taskforce (predecessor of Partnerships UK) Martin participated in many of the largest and most complex projects in the transport sector.

Martin is a member of DfT’s Rail Franchising Advisory Panel and the HM Treasury IUK Client Working Group.

-

Acknowledgements

Andrew Wolstenholme OBE, Crossrail Ltd, Interview

Steve Allen, Transport for London, Interview

Claire Moriarty, Department for Transport, Interview

James Stewart OBE, KPMG (Crossrail Ltd non-Executive Director 2008-2011), Interview, Review

David Hughes, Transport for London, Interview

Doug Oakervee CBE, Crossrail Ltd (2005-2008), Interview

Terry Morgan CBE, Crossrail Ltd, Interview

Michael Cassidy CBE, Crossrail Ltd (non-Executive Director), Interview

Robert Jennings CBE, Crossrail Ltd (non-Executive Director), Interview

Richard Threlfall, KPMG, Review

-

Peer Reviewers

Professor Andrew Davies, Bartlett School, University College London

Martin Samphire, Association for Project Management - Chairman, Infrastructure Group