Employment Relations on a Major Construction Project

Document

type: Case Study

Author:

Andrew Eldred MA, MSc

Publication

Date: 09/07/2018

-

Abstract

This case study outlines differences in the context for employment relations [ER] on some of the largest UK major construction projects, and how these differ from a more typical project context; how Crossrail’s own approach to ER evolved over the lifetime of the project; the ways in which this approach both resembled and differed from approaches on other recent major projects, plus the reasons why; and, finally, some outcomes, lessons learned and recommendations for future projects.

-

Read the full document

INTRODUCTION AND INDUSTRY BACKGROUND

This first section establishes the broader context for Crossrail’s approach to supply chain ER. It explains both how major projects are somewhat different from more typical construction projects in this regard, and the ways in which previous major project clients have addressed the issue.

The client’s role

Most construction clients pay little heed to ER on their projects, leaving such matters to contractors and subcontractors to manage for themselves.[1] The risk calculus on the largest, most strategically significant infrastructure projects -involving thousands of workers and with budgets measured in the billions of pounds – tends to be rather different, however, owing to a range of special factors, such as:

- The presence of multiple main contractors and subcontractors on one project, with the potential that ER practices and/or disputes affecting one contract or employer may have negative knock-on effects for others;

- The disproportionate financial, programme and reputational risks liable to arise from any contractor mismanagement of ER, breaches of minimum employment standards and/or stoppages of work from industrial action;

- The expectation that major projects will observe good practice in relation to ER, as in other areas; and

- The likelihood of higher than normal trade union interest and involvement, linked to the project’s strategic significance, its potential to act as a shop window for union strength, and greater opportunities to organise a large and relatively stable workforce.

Accordingly, whilst it remains unwise for major-project clients to get involved in the day-to-day minutiae of ER, they do have a legitimate interest in assuring themselves and other stakeholders that contractors are managing these matters appropriately and in accordance with their contractual obligations.

Previous projects

The closest precedents for Crossrail at the time it was considering its approach to ER in the late 2000s were the Jubilee Line Extension (1993-1999), the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (1998-2007), Heathrow Terminal 5 (2002-2007), and the Olympic Park (2007-2011).

The Jubilee Line Extension suffered considerable disruption from industrial action, at least in its later phases, which was subsequently widely blamed on the client London Underground’s lack of a proactive ER strategy. By contrast, the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (also known as “High Speed 1”) sought to balance the principle that contractors are best placed to manage construction supply chain ER with a measure of client-led ER coordination. This included the incorporation of key principles of good ER management into a contractual code of practice, ongoing oversight of contractors’ performance by the project’s head of ER, and occasional – mostly informal – direct contacts with construction trade union officials.

Client involvement in supply chain ER came even more to the fore on the two later projects. This was especially the case on Heathrow Terminal 5 [T5] where the client BAA sponsored the signing of a self-consciously “mould-breaking” Major Projects Agreement [MPA]. The MPA fixed actual terms and conditions for all mechanical, electrical and plumbing [MEP] workers on the project, including project-wide bonus arrangements; required compliance with PAYE direct employment; and, established project-wide trade union representative arrangements. BAA incorporated the MPA into all relevant contracts.[2]

On the Olympic Park, the Olympic Delivery Authority resisted calls to adopt an MPA, but came under sustained pressure to enter into an alternative agreement with the construction trade unions. After nearly a year of negotiations, both sides finally signed up to a Memorandum of Agreement [MoA] in 2007, which was applicable to all construction work on the project. Instead of setting actual rates of pay, benefits and allowances, the MoA guaranteed minimum terms and conditions, benchmarked to the main National Working Rule Agreements (NWRAs) which historically have covered each sector of the industry. These NWRAs vary from comparatively loose, minimum terms arrangements (e.g., the CIJC agreement for civil and building operatives) and more prescriptive agreements (most notably, the JIB agreement for the historically more ER challenging electrical contracting sector). Like the MPA, the MoA also contained a commitment to what was termed the “ethos of a directly employed workforce”. The ODA further undertook to facilitate trade union access and representative arrangements, although the specifics of these were left to be agreed contract by contract. Finally, the ODA promised to play “an active monitoring and coordinating role to ensure the consistent and fair application” of the MoA by different Tier 1 contractors, and to this end incorporated both the MoA and a supporting ER code of practice – partly based on measures used at T5 – into its contracts.[3][4]

Figure 1 – Olympic park Construction

EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS ON CROSSRAIL: AN EVOLVING APPROACH

Like both T5 and the Olympic Park, Crossrail involved multiple Tier 1 contractors and a large, shifting population of subcontractor firms and construction workers. The project consisted broadly of two main phases: tunnelling, which ran mainly from 2011 to 2015; then, stations construction and rail systems installation, which first got properly under way in 2014 and continued until 2018. Both phases saw peak workforces of around 10,000, but made up very differently: the former consisting principally of tunnelling and civil engineering workers – amongst whom union organisation has tended to be relatively weak – whilst the latter was made up of a more diverse group of specialist building, rail and MEP operatives – of whom, electricians have been most closely associated with effective union organisation and industrial action in the past. The ER regime on Crossrail also underwent a degree of change over time. The main stages of this evolutionary process were as follows:

There was a comparatively “light-touch” approach at the start, exemplified by:

- An emphasis in Crossrail’s contractual provisions on each Tier 1 contractor’s responsibility for managing ER, including establishing a contract-specific ER policy which it was then expected to communicate to all its subcontractors, monitor and enforce;

- Some limited minimum employment standards requirements. These included relatively onerous obligations on Tier 1 contractors to comply with the London Living Wage [LLW] as a minimum and to ensure that their subcontractors and labour suppliers did likewise. Other provisions, drawn from the Ethical Trading Initiative’s [ETI’s] Base Code, echoed some of the same themes as those in the ODA’s MoA, but without much in the way of specific detail. For example, Tier 1 contractors were required to maximise “regular employment”, observe “industry benchmark” terms and conditions, and respect individuals’ right to join a trade union and trade unions’ freedom to organise and bargain collectively;

- No binding coordination requirements on Tier 1 contractors in connection with ER, apart from those covering auditing and reporting in respect of the LLW; and

- Crossrail’s decision not to enter into a direct agreement with the construction trade unions – in contrast to BAA and ODA.

As tunnelling work progressed during 2011 and 2012, support started to grow within both Crossrail and contractor organisations for a more centrally coordinated ER regime. This change of heart arose largely because of the following pressures:

- Inconsistencies in contractors’ ER capability and approach. Contrary to contractual requirements, most Tier 1 tunnelling contractors and joint ventures either developed no ER policy at all, or relied upon one that was inadequate for the task. Some Tier 1s possessed little in-house ER expertise, and even where such expertise did exist ER considerations could be ignored or overruled in favour of shorter-term operational or commercial interests. Knowledge and scrutiny of subcontractors’ and labour suppliers’ employment practices were quite often limited or non-existent;

- PAYE direct employment. Whereas some tunnelling Tier 1s made serious attempts to maximise compliance with PAYE direct employment (or “regular employment”, in ETI Base Code parlance), others did not. The former group started to express concerns about labour migrating from their sites to their non-compliant peers’, owing to the higher potential take-home earnings available under “self-employed” status – increasing their own costs and endangering their ability to maintain planned production rates. Some contractors alleged that Crossrail was not doing enough to prevent non-compliances, and pressed for greater consistency and coordination across the project, led by the client;

- Trade union campaigning. Criticisms of ER on the project from trade unions also began to increase, culminating in a significant campaign led by Unite against one of the tunnelling joint ventures from September 2012 onwards.

In response, from late 2012 there started the establishment, step by step, of a more centrally coordinated ER regime. Although led by Crossrail, this process also relied on the involvement and agreement of Tier 1 contractors, and included:

- Establishment of a regular liaison and communications forum for Crossrail and the contractors to discuss ER matters;

- Drawing up of an ER code of practice by this forum, based on T5 and Olympic Park models (although, unlike on the earlier projects, this code was necessarily non-contractual (i.e., voluntary) in nature);

- Appointment of a new full-time Crossrail Head of ER, based in the Delivery Director’s team, and reporting jointly to the Programme Director and Talent and Resources Director;

- Establishment of a thrice-yearly Crossrail/ trade union forum, attended by construction trade union officials and Crossrail’s Delivery Director, Talent and Resources Director and Head of ER. As well as briefings from Crossrail on health and safety, construction progress, skills and employment, these meetings were intended to provide the trade unions with an opportunity to raise any concerns, which Crossrail could then either address directly or raise with the Tier 1 contractor or contractors concerned.

ER performance assurance framework

Whilst the developments outlined above eventually resulted in an ER regime on Crossrail which resembled in some respects that on the Olympic Park [see further Table 1, below], the introduction of a performance assurance framework [PAF] at the end of 2014 represented something of an innovation. The ER PAF mirrored six others developed by Crossrail previously, covering various disciplines, including health and safety, environmental, quality and commercial performance. Previous legacy reports on the PAF regime in general and an area closely related to ER, Social Sustainability detail how these were developed.

Approximately every six months, Tier 1 contractors’ management of site ER was scored against pre-agreed criteria, based on contractual minimum requirements – “basic” compliance – and accepted good/ best practice – “value-added” and “world-class” compliance. The introduction of levels of performance above mere contractual compliance helped to overcome gaps and weaknesses in some of the original contractual requirements. The four themes on which Tier 1 contractors’ performance was assessed were:

- ER risk management, including a more proactive approach to specific MEP workforce risks (value added) and identifying specific ER opportunities (world class);

- Minimum employment standards, recognising stronger policies on some contracts with regard to supply chain PAYE direct employment and NWRA compliance (value added/ world class);

- Workforce engagement, including relations with trade unions; and

- ER governance, both at contract level (strengthening relations between Tier 1 ER leads and other disciplines) and in relation to the client and other Tier 1 contractors (underpinning the collective coordination mechanisms established from 2012 onwards).

A copy of the final iteration of the ER PAF is available here . Some findings from the PAF process, as well as other ER outcomes, are outlined further below.

OUTCOMES

This section records the responses of different stakeholders to the ER regime on Crossrail, including responses as coordination processes were strengthened from late 2012 onwards. Those considered include the construction trade unions, Tier 1 contractors and the on-site workforce itself.

Figure 2 – Construction workers on site

Trade union responses and industrial action

In the contemporary UK construction industry, strikes and other conventional forms of industrial action are increasingly rare.[5] This reflects a broader UK-wide decline in the incidence of industrial action, as well as long-standing structural barriers to collective action within the construction sector, including low levels of trade union membership and organisation and high levels of subcontracting, agency working and self-employment.[6] Major projects, with their higher profile, larger workforce, greater use of direct employment, and longer time-span tend to be more prone to industrial action, with the Jubilee Line Extension [see “previous projects” above] widely cited as the precedent to be avoided at all costs.

Despite a policy of maximising direct employment, Crossrail largely avoided conventional industrial action until quite late on. Indeed, in 2014 the project’s “regular employment” policy may even have protected it from industrial action then occurring elsewhere because of changes to agency workers’ employment status brought about by new tax rules on employment intermediaries.[7]

Once the major Unite campaign referred to above was eventually resolved in early September 2013 union-employer relations mostly settled down, with Crossrail continuing to encourage Tier 1 contractors and construction trade union officials to engage positively with one other. Site access arrangements for local union officials were put in place on all significant contracts, drawn up and operated by the Tier 1 contractors concerned. Whilst both UCATT and Unite succeeded in recruiting new members and securing the election of shop stewards and safety representatives, some local officials now and again expressed disappointment at the levels of membership and site-level organisation achieved.

Generally, the local union officials nominated to attend the thrice-yearly information sharing sessions with Crossrail raised few concerns. Between 2014 and 2016, Crossrail supplemented these collective sessions with more informal, one-to-one meetings between more senior trade union officials and the Programme Director, supported by the Head of ER. These meetings were usually positive and useful.

Trade union activity increased once more in 2016 with the growth in the size of the MEP workforce: Unite’s traditional power-base in construction. Local officials started to raise expectations that a project-wide bonus could be negotiated with and paid for directly by Crossrail. To a degree, the union’s hand was strengthened by a simultaneous cyclical upturn in the London construction market, resulting in a sizeable leap in the rates of pay being offered to electricians to work on numerous projects, typically on a false “self-employed” basis. Crossrail declined to enter into such negotiations, however, on the ground that under its contracts bonus arrangements were a matter for Tier 1 contractors and/or individual employers to determine and accommodate within their existing target costs.

Following a relatively short-lived project-wide bonus campaign in late 2016, Unite did manage to negotiate contract-level bonuses with some MEP employers, linked to new working practices and productivity milestones. Surprisingly to some, this did not bring about any “domino effect” on the remaining contracts, although a few other MEP employers quietly introduced new bonus and/or working arrangements at times of their own choosing throughout 2017. Still other employers continued to pay basic rates of pay only, sometimes on contracts where another employer was paying a bonus – once again, upsetting established notions that divergences in pay arrangements on construction major projects necessarily lead to disputes. Although some industrial action did occur during 2016-18, principally involving electricians, this was usually short-lived and confined predominantly to one contract.

Tier 1 contractor ER performance

Overall, Tier 1 contractors’ management of ER during the stations and system-wide stage of the project was significantly better than during the earlier tunnelling stage. Up to a point, this reflected the fact that the main stations and system-wide Tier 1s were both better resourced with specialist ER expertise, and readier to take account of the risks from mismanagement of ER. Another factor, however, was the strengthening of interpersonal links between the Crossrail and Tier 1 ER leads, and between each organisation’s respective ER function and its own project team, fostered by regular contacts through the various coordination measures adopted since late 2012, including the ER PAF process. These interpersonal connections were vital since, in the absence of strong contractual provisions, Crossrail could improve on and adjust its original “light-touch” ER regime only with contractors’ and its own teams’ consent and cooperation.

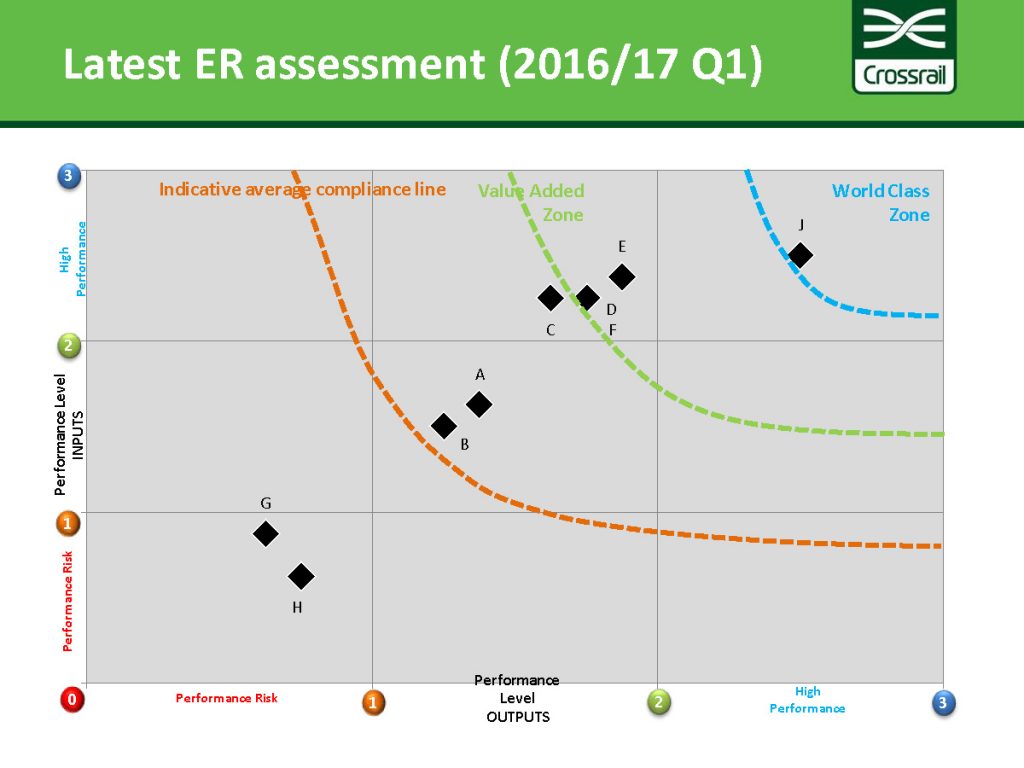

Figure 3 below provides a pictorial representation of the absolute and relative performance of the nine largest station and system-wide contracts at the final ER PAF assessment in Spring 2016. By this time, nearly half had progressed to a PAF rating of “value-added” performance or better: an important benchmark since back in 2014 this had been identified as the performance level required for the historically higher-risk MEP phase of the project. Regrettably, four contracts (A, B, G and H) were still falling well short of this level, of which two (G and H) remained stuck below compliance with basic contractual requirements.

Figure 3 – Contract ER PAF performance ratings Spring 2016

Judged in terms of both subsequent vulnerability to industrial action and contractors’ effectiveness in responding to such action, the ER PAF ended up demonstrating quite a high degree of predictive validity. Only one of the higher performing contracts ultimately suffered from unofficial industrial action during Unite’s bonus campaign, and the Tier 1 contractor concerned was able to defuse the situation comparatively swiftly and effectively. By contrast, all four of the lowest performing contracts – H, G, B and A – proved vulnerable during the early stages of the bonus campaign in late 2016. The consistently lowest performing contract, H, also suffered the worst record in relation to industrial action between 2016 and 2018.

Workforce responses

With up to two dozen major contracts running concurrently, multiple sites, and hundreds of different employers, it was never feasible for Crossrail to measure the overall quality of the ER “climate” on the project. As with most workplaces, construction sites are never entirely free of one issue or another, but on Crossrail, for the most part, resolution of grievances seems to have occurred either informally, through formal grievance procedures, or via site safety forums and observation/ feedback schemes. The latter, whilst originally established by Tier 1 contractors to encourage better communications and engagement on safety and welfare matters, also came to be used on occasion by workers to raise other collective concerns, such as pay disparities, working hours, bullying and racism. Often, although not always, Crossrail also became aware of these issues from personal contacts with Tier 1 ER leads, or the latter’s formal ER reports every eight weeks. Now and again, local trade union officials also contacted Crossrail for assistance in encouraging a Tier 1 contractor to deal more swiftly with a specific case. Latterly, Crossrail’s Head of ER started to be copied in on weekly summaries of worker observations and feedback collated by the Crossrail Health and Safety team, forwarding any ER-related concerns on to the relevant Tier 1 ER leads.

Helpdesk complaints

In 2013, Crossrail established a system for managing employment and related concerns from workers who were starting to call the project’s public Helpdesk. This system, closely based on that on the Olympic Park, involved Helpdesk staff first taking down a worker’s details and account of the complaint, and passing these on to the Crossrail Head of ER. He then forwarded the complaint to the Tier 1 contractor concerned for further investigation, anonymising it if appropriate. On receiving the Tier 1 contractor’s account of the outcome of its investigation, the Head of ER drafted a short summary response which Helpdesk staff finally relayed back to the complainant.

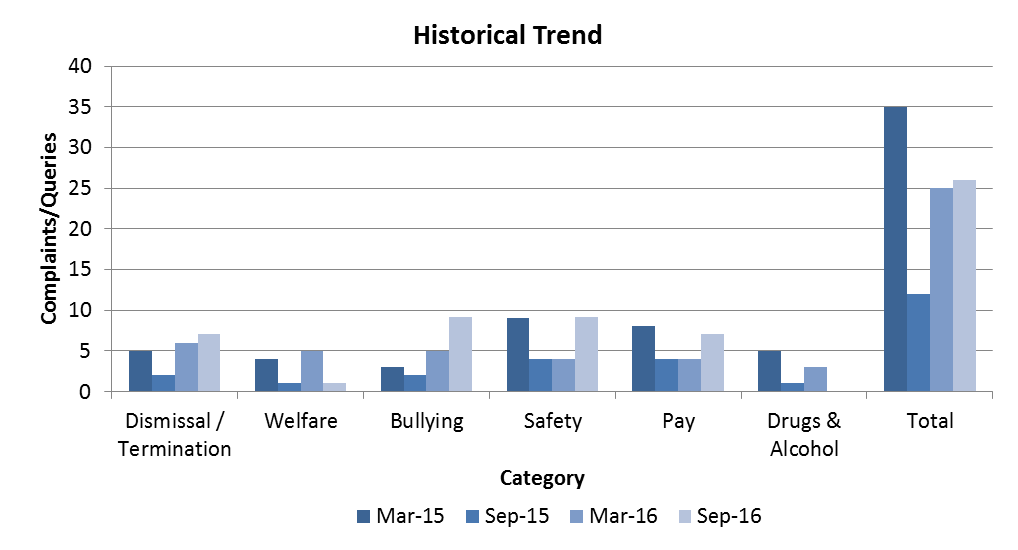

From 2015 Crossrail began to analyse worker concerns more systematically, reporting the findings to Crossrail’s Executive Committee every six months. Figure 4 summarises findings in relation to the volume and subject matter of complaints over successive six-month periods. This confirms that there was a steady flow of calls to the Helpdesk, with some peaks in activity, and pay, dismissals, bullying and safety consistently among the most popular topics.

Figure 4 – Volume and subject matter of Helpdesk employment complaints: 2015 and 2016

Employees of employment businesses and labour-only subcontractors were far more likely to contact the Helpdesk than those working for the Tier 1 contractor or specialist trade subcontractors. This may reflect difficulties in operating effective in-house grievance procedures when employer responsibilities are split: in this case, between the employment business/ labour-only subcontractor who pays the employees, and the Tier 1 contractor who supervises them. Notably, few if any supply chain workforce complaints were submitted to equivalent helplines run by Tier 1 contractors. This may betray a lack of confidence that matters would be properly investigated, fear of reprisals and/or perceptions that it was best to go “straight to the top” (i.e., the client).

LESSONS LEARNED AND RECOMMENDATIONS

As has been explained above, the client and contractors on the Crossrail project had to adjust their expectations and approach to ER over the life of the project. This final section aims to provide some insights into why this proved to be necessary, and what major-project clients in the future might usefully do to minimise risks and maximise opportunities in the ER field.

Analytical overview: inter-organisational regulation of ER in a UK construction context

UK construction ER is little studied, and major-project ER even less so. The handful of analyses of UK major projects published over the past two decades have all tended to concentrate on a single project, providing an explanation for the specific ER regime adopted and a – mostly favourable – assessment of the ER outcomes achieved.[2] [4] [8] Inter-project comparisons, including consideration of why one client might adopt a more or less “hands-on” ER approach than another, are largely absent.

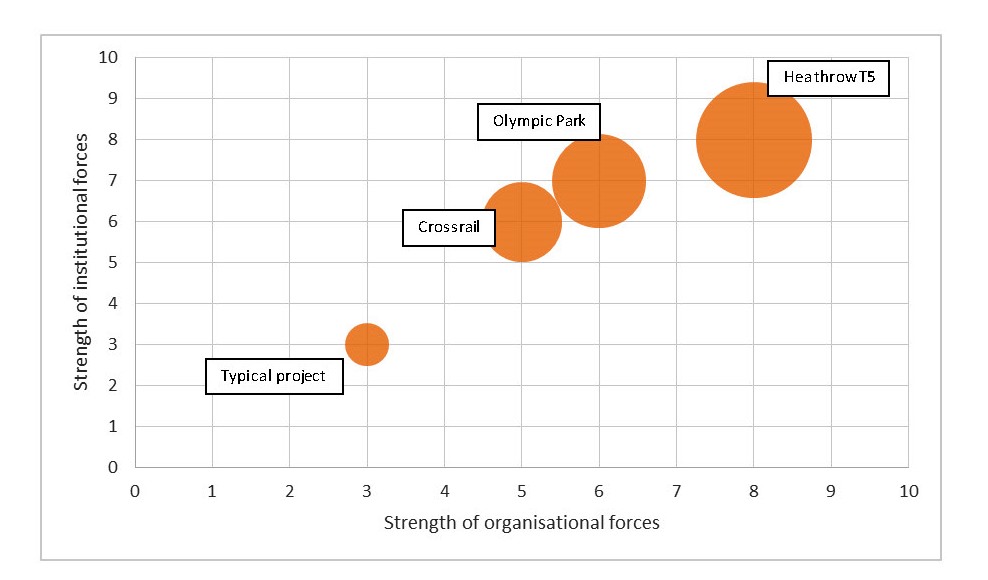

Supply chains are hardly unique to construction, of course. In other economic sectors, such as automotive, consumer goods and public services, studies of the role played by clients and other “lead firms” in regulating ER within supply chains are relatively plentiful and may generate a potential theoretical framework for making sense of the choices made by clients on construction major projects.[9][10][11] Marchington and Vincent’s (2004) “three forces framework”, for example, predicts that each client’s readiness to involve itself in supply chain ER is liable to be influenced by the specific array of institutional and organisational forces operating on the client, its supply chain organisations and the transaction(s) between them.[12] For these purposes, “institutional” forces may cover (among other things) legislation, public policy, vocational education and training systems, trade unions, employer associations and collective bargaining, whilst “organisational” forces include each client organisation’s history, structure, policies and interests, along with external influences such as CSR and the purpose and power dynamics of the inter-organisational transaction itself.

Applying the three forces framework to four UK construction projects, one hypothetical and the others real, it is possible to map, in broad terms, the relative strength of institutional and organisational forces in each case, as set out in Figure 5 below. This indicates a large gulf between the hypothetical “typical” construction project and all three major projects, corroborating the argument made at the start of this paper that major projects are “different”. Just as importantly, Figure 5 also displays a discernible pecking order between the three major projects, reflecting different intensities of institutional and/or organisational pressure to adopt a more “hands-on” role in relation to supply chain ER.

Figure 5 – Determinants of construction client ER involvement

(drawing on Marchington and Vincent’s (2004) “three forces framework”).

Typical UK construction project: little or no client ER involvement

On a typical construction project in the UK, these forces are comparatively weak. In institutional terms, on most sites levels of trade union organisation and compliance with industry collective agreements are low, industrial action largely unheard of, and the incidence of false “self-employment” often high. UK public policy and regulation also impose few ER obligations beyond minimum statutory compliance and, given high levels of “self-employment”, even this threshold has little practical relevance for much of the workforce.

Likewise, organisational factors tend to encourage a “hands-off” client approach towards supply chain ER: for example, most clients procure their projects from main contractors on lump-sum, “turn-key” contracts – in other words, transferring most if not all project risks across to the main contractor. Other than some initial due diligence during procurement, there are few expectations that construction clients will oversee the construction works that are then carried out on their behalf, and if something subsequently goes wrong it will normally be the main contractor who suffers most of any reputational damage and the inevitable financial hit, rather than the client.

Heathrow Terminal 5: strong client ER involvement

In ER terms, the Heathrow Terminal 5 [T5] project has proved something of an outlier in its adoption of a prescriptive project-wide agreement, the MPA, and project-wide trade union organisation. Whilst portrayed at the time as an example of “best practice”, the MPA model has not been adopted elsewhere – at least until EdF’s Hinkley Point C project – and is better understood in terms of the almost unique array of institutional and organisational forces operating in a particular time and place. These included:

- The scale and importance of the project. The final budget for T5 was £4.2bn, making it the largest construction project seen in the UK for many years. For BAA, the commercial and strategic significance of a new terminal building for its most important airport meant that the project had to succeed and be seen to succeed.

- BAA’s active involvement in all other aspects of construction. Owing to T5’s importance, BAA effectively entered into joint venture partnerships with its construction contractors in delivering the project. Key specialist contract packages which would normally have been subcontracted by a main contractor – for example the MEP works – were instead procured directly by the client.

- BAA’s direct exposure to project risks. Reflecting this active involvement, as well as a desire to encourage collaboration, flexibility and innovation among its contractors, BAA awarded key contracts on a reimbursable, “cost-plus” basis – in other words, absorbing many of the potential project risks itself.

- Concerns about attracting and retaining labour. Heathrow’s position to the west of London, a booming construction market, and the several thousand construction workers T5 needed to attract, convinced BAA that it had to offer above-market terms and conditions over the lifetime of the project.

- Perceived vulnerability to industrial action. One of the key risks identified by BAA early on was industrial action. Partly this was because of the project’s comparatively high MEP content – the MEP workforce, as has been seen, being most often associated with industrial action risks. Another factor was that T5 was a single site, with common welfare facilities and a shared site entrance/ exit, which it would be relatively easy to close off with a few demonstrators or pickets. BAA was also very concerned by the recent precedent of the Jubilee Line, where ER instability had become endemic.

- Institutional factors favouring social partnership. In ER terms, BAA was a “brown-field” client, with a large, permanent airport workforce based close by, and high levels of trade union density and organisation, including some unions that also represented construction workers. By deciding to sponsor the MPA and other forms of union and worker involvement, BAA may also have been responding to the social partnership trend of the late 1990s, then in favour with the UK’s New Labour government and business organisations self-identifying as “progressive” in their approach to ER at the time.

Olympic Park: a hybrid regime

Although the ODA adopted some elements from T5’s regime on the London 2012 Olympic Park, its MoA was not as prescriptive as the MPA, and details of the management of ER, including trade union engagement and organisation, were largely left to individual Tier 1 contractors and employers to manage for themselves. This hybrid form of ER regime arguably reflected the distinctive combination of institutional and organisational forces affecting the Olympic Park project, which in some respects resembled but in others differed from those on T5. For example:

- The scale and importance of the project. The budget for Olympic Park construction was considerably higher than T5, at £7bn, and largely funded from public tax revenues. Furthermore, in view of the prestige and risks associated with hosting the Olympic Games in London, the project was inevitably subject to a high degree of public, media and political scrutiny, especially in the early years.

- The ODA’s Tier 1 strategy. Although relatively “hands-on” in some areas (e.g., health and safety, environmental protection, diversity, skills and employment), the ODA mostly avoided direct participation in construction delivery itself – unlike BAA on T5. Instead, the ODA divided the Olympic Park up into separate geographical zones, and awarded each zone to a Tier 1 contractor, who was then responsible for delivering the venue and/or supporting infrastructure within that zone. Each Tier 1 contractor also had responsibility for awarding subcontracts and managing all associated matters within its zone, such as principal contractor duties under safety legislation, provision of workforce welfare facilities, and site security. The role of the ODA and its delivery partner, CLM, was to ensure that each Tier 1 contractor continued to deliver its work in line with its contractual obligations, and to provide certain Park-wide logistical services, including bussing, perimeter security and delivery of materials.

- The ODA’s risk-sharing approach. Whilst the ODA rejected a lump-sum option on all but a few contracts, it also declined to adopt the T5 model of fully reimbursable cost-plus arrangements. Instead, the ODA offered its Tier 1 contractors “target-cost” reimbursable terms, allowing both the client and the contractor to benefit when work was delivered at below target cost, but also to share the financial pain if a target was missed.

- Less acute concerns about labour attraction and retention. The Olympic Park’s location in east London, close to where many construction workers live, and with relatively good local transport links, persuaded the ODA that it would probably be able to attract and retain sufficient numbers to work on the project, so long as it ensured reasonable minimum levels of pay, welfare and safety performance. A cyclical downturn in the construction market after 2007 further reinforced this perception and helped pre-empt any renewal of trade union calls for an MPA-style superior terms-and-conditions arrangement.

- Perceived lower vulnerability to industrial action. The volume and complexity of MEP work on the Olympic Park were somewhat less than on T5, and therefore the likelihood of industrial action was also perceived as lower. The ODA moreover considered that the impact of any industrial action was likely to be reduced by the partition of the Olympic Park into separate zones, each with a different Tier 1 contractor and set of MEP subcontractors; by staggered construction start and finish dates, meaning that there should be no single MEP workforce “peak”; and, by the provision of multiple entrance and exit points around the Park’s perimeter, reducing the likelihood that the entire site could be shut down.

- Institutional factors favouring some degree of direct trade union engagement. As well as facing a lower perceived industrial action risk, the ODA was also a “green-field” client in ER terms, with no established workforce or trade union recognition arrangements – suggesting less industrial pressure on the ODA than BAA to adopt a strong “social partnership” approach. On the other hand, trade union political influence at both national and local level represented a significant consideration, at least during the project’s early years, which was reflected in the appointment of a senior former Unite official as an ODA Board non-executive director. This influence played an important role in encouraging the ODA towards entering into some form of direct agreement with the construction unions, even though it successfully resisted all attempts to get it to sign up to a T5-style MPA.

Given that some of the forces described above pushed in one direction, whilst others pulled in another, it is perhaps unsurprising that the ODA initially had difficulty in settling upon a coherent and consistent vision for management of ER on the Olympic Park – reflected in the long, drawn out MoA negotiations with the construction trade unions. The ODA’s final hybrid solution effectively reconciled these conflicts by assigning to the client the roles of setting minimum standards requiring Tier 1 contractors to submit regular ER reports; assuring contractors’ compliance with minimum standards and broader principles of ER good practice, including frequent payroll audits; facilitating contractor coordination on matters of shared interest and concern; and, maintaining a measure of high-level engagement with the construction trade unions. All other aspects of the management of ER, including site-level trade union relations, remained within the jurisdiction of Tier 1 contractors and individual employers.

Crossrail: an evolving, consensus-based regime

The organisational and institutional context for the Crossrail project resembled quite closely that of the Olympic Park. As well as a multi-billion pound budget and high levels of public and media interest, Crossrail adopted a similar Tier 1 strategy and risk-sharing approach, including a preference for target-cost reimbursable contracts. Even more so than on the Olympic Park, the linear structure of the Crossrail project naturally leant itself to the award of Tier 1 contracts based on separate geographical zones, with less need for Crossrail to offer centralised logistical support in relation to deliveries, site transportation and security. Despite being a wholly-owned subsidiary of Transport for London [TfL], Crossrail was also, like the ODA, a “green-field” client in ER terms, with no legacy workforce or ER arrangements, and no future role in the running of the Elizabeth Line railway which its contractors were building.

In some respects, the institutional and organisational pressures on Crossrail to adopt a “hands-on” approach to supply chain ER were weaker and less obvious than those the ODA had faced. Changes of governing party, first in London and then Westminster, meant that trade union political influence was significantly weaker by 2010, when the Crossrail project was getting under way, than three years earlier when the ODA had signed the MoA. At least as importantly, many of Crossrail’s own employees came from a “typical project” background where, as has already been seen, client organisations generally adopt a “hands-off” approach to ER. From this perspective, the ER regimes on T5 and the Olympic Park may have appeared alien and unnecessarily risky – largely explaining the initial preference for a “light-touch” approach, described above.

Over time, the different ER risk calculus on major projects [see “The client’s role” above] necessarily drove a change of approach, as outlined above. By 2014, therefore, Crossrail and its Tier 1 contractors had effectively instituted by agreement an ER regime which largely replicated the hybrid ER model previously adopted on the Olympic Park, [see further Table 1, below].

Having considered the different forces underpinning client ER strategies, and how these contributed to a change of approach on the Crossrail project, the rest of this paper will focus on specific lessons learned and recommendations.

Establishing a “best-fit” client ER strategy

Construction clients are well-advised to keep out of the day-to-day management of supply chain ER, which is better left to main contractors and individual employers to sort out in partnership with their workforces and/or trade unions.

Nevertheless, in the case of the largest major projects, additional considerations come into play, which clients in these instances cannot afford to ignore [see “The client’s role” above]. In designing a proactive ER strategy to help support their project’s budget, programme and reputation, clients should consider which combination of ER strategic principles, policies and practices represents the “best fit”, rather than reaching for some elusive goal of “best practice”. [13]

Identifying what constitutes “best fit” will involve taking account of the various institutional and organisational forces likely to have some impact on the project. In certain cases (e.g., the heavily regulated and unionised engineering construction sector), best fit may require a high degree of ER coordination even on relatively small projects; [14] in others, a generally less demanding institutional and organisational environment may permit a comparatively light-touch ER regime.

In the case of Crossrail, a light-touch regime ultimately proved unsustainable, reflecting a demanding and complex array of institutional and organisational forces much closer to the Olympic Park and T5 projects than to a “typical” construction project. Fortunately, Crossrail and its Tier 1 contractors were able by consensus to retrofit various elements of a stronger ER regime from late 2012 onwards, so that when the project faced the double challenge in 2016-17 of a cyclical upturn and concerted trade union action, it managed to withstand both comparatively unscathed. Clearly, with the benefit of hindsight, it would of course have been preferable if the project’s ER strategy had been closer to a “best fit” from the outset.

Recommendation 1: Clients on construction major projects should take care when selecting from the range of available ER principles, policies and practices that the choices they make represent the best strategic fit for their project. Relevant considerations for these purposes are likely to include some of, or all, the following:

a) Scale and importance of the project;

b) Construction strategy;

c) Commercial risk strategy;

d) Labour attraction and retention strategy;

e) Assessment of industrial action risks;

f) Institutional factors, including:

i. “Brown-field” or “green-field” ER context;

ii. Legal and collective bargaining contexts;

iii. Likely trade union density, militancy and organisational effectiveness;

iv. Local and national political contexts.

g) Potential exposure to future cyclical upturns/ downturns, policy and/or legislative changes, and other relevant changes of circumstance.

Determining the most appropriate form for any direct trade union relationship

Although the construction trade unions would clearly have preferred a project-wide agreement with Crossrail, the fact that some limited industrial action did occur on the project need not be taken as proof that Crossrail erred in declining to enter into such an agreement. Industrial action also occurs on projects which have adopted prescriptive, project-wide agreements, some of it much more serious and persistent than anything experienced on Crossrail, and so assertions that such agreements necessarily reduce the chances of ER instability are in danger of appearing over-simplistic.

Whilst most major-project clients will naturally prefer positive relationships with trade unions, they are also likely to vary in their appetite to support a project-wide agreement, whether of an MPA or MoA type, or at all. This variability stems from a different balance of institutional and organisational factors in each case. Those opting to take on the additional risk and costs associated with a comprehensive, project-wide agreement like the MPA are likely to be in the minority, and to be influenced by similar considerations to those driving BAA on its T5 project.

Recommendation 2: For ER, ethical and pragmatic reasons, clients on major construction projects should take all reasonable steps to respect and protect trade union freedoms and encourage positive trade union engagement. As at T5 itself, the benefits of supporting a fully-fledged project-wide agreement like the MPA will probably be greatest where:

a) Construction work and related matters such as welfare facilities and safety management are organised project-wide, rather than disaggregated into autonomous and physically separated contract sites;

b) The client takes on a high degree of commercial risk, including risks of delays and cost escalation from industrial action;

c) Offering employment terms and conditions above industry norms is believed to be necessary for attracting and retaining sufficient labour of the right quality;

d) Without an agreement, the likelihood and/or potential impact of industrial action is understood to be high;

e) The client is a “brown-field” organisation in ER terms, with significant relationships with GMB and/or Unite (the two surviving trade unions in the construction sector); and

f) Other institutional forces favouring a prescriptive, all-encompassing trade union agreement are strong.

Addressing the issue of minimum employment standards

Apart from issuing policies against the worst – and most unlikely to occur – abuses, such as illegal working and forced labour, UK construction clients generally pay little regard to employment standards on their projects. Both PAYE direct employment and compliance with industry NWRAs carry additional costs, which typically both clients and contractors are keen to avoid.

By contrast, all the major projects previously mentioned in this legacy report have operated explicit policies in support of direct, or “regular”, employment and alignment with NWRA pay and benefits. Partly this can be explained as a response to trade union opposition to widespread “self-employment” and non-observance of NWRA terms and conditions. However, other important reasons why clients can and should do what they can to support PAYE direct employment and the NWRAs include:

- Safety, productivity and quality. Directly-employed workers are perceived generally to be safer, more productive and more interested in quality standards. This overall superiority derives from, among other things, the mutual benefits and assurance which long-term employment relationships can offer to employers and employees, additional employer investment in training and development, and higher levels of work commitment and flexibility.[15][16]. Direct employment is also almost always a precondition for a sustainable system of workforce training and development – so that endemic construction skills shortages in recent years can largely explained by the construction industry’s own increasing dependence on subcontracting and false “self-employment”.

- Long-term employees are generally less likely than short-term “self-employed” workers to leave a job before it is completed, especially during cyclical upturns in market-driven labour rates. Consistently applied direct employment policies can also protect against migration within one project (i.e., from one contractor complying with PAYE direct employment, to another offering higher take-home pay on “self-employed” terms).

- Fair employment. PAYE direct employment in the UK gives individuals access to social security benefits, paid holidays, statutory sick pay and pensions auto-enrolment, none of which is currently available to the self-employed. Likewise, NWRA terms and conditions are jointly agreed by the “social partners” and provide further enhanced benefits in relation to holidays, sick pay, pensions and life-and-accident cover, as well as rates of pay usually well above both the statutory and voluntary living wage benchmarks.[17]

- Ethics and reputation. Much of what passes for “self-employment” in UK construction is false and designed principally to avoid the tax and national insurance costs of direct employment.[18] Given the budgets, high profile, and in some cases taxpayer funding, of large infrastructure projects, simply turning a blind eye to false self-employment – which most construction clients choose to do – is not an ethically or reputationally attractive position for a major-project client to adopt. For similar reasons, major-project clients may struggle to justify construction workers on their sites receiving terms and conditions below the minimum benchmarks set out in NWRAs.

- Community engagement. Most large projects are required to off-set the disruption and inconvenience caused by construction works by means of community engagement initiatives, including commitments to jobs and training for local people. Where, however. employment practices and terms and conditions are poor, or even illegal, there is an obvious risk that such initiatives could backfire.

Despite the validity of these arguments, there is a deep in-built resistance within many client and Tier 1 contractor organisations to the idea of regulating supply chain employment standards beyond superficial legal compliance. This resistance is especially strong among those charged with drafting, procuring and administering commercial contracts and subcontracts. Whilst it is true that some types of commercial clause are unlawful (e.g., compulsory union recognition, or “closed shop” clauses), and that skills shortages in some construction trades can make an unqualified commitment to direct employment impracticable, most of these objections can be relatively easily overcome: for example, by requiring alignment with NWRAs as minimum benchmarks, rather than compliance with NWRAs per se; and, by permitting deviation from PAYE direct employment in certain defined circumstances, provided the client is notified in advance. Recent changes to EU and UK public procurement law – most notably the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 – have now made “social clauses” of this sort easier to implement than at any time since the 1980s.

It goes without saying that contractual provisions are worth little if they are insufficiently clear, poorly communicated and/or inadequately enforced. Crossrail’s reliance on the broad-brush principles of the ETI Base Code could have been supplemented by a more detailed explanation of expectations, for example, in relation to “regular employment” and “industry benchmark standards”, ideally as part of an ER code of practice incorporated into each Tier 1 contract. Furthermore, it was only after Crossrail’s change of approach from 2012 onwards that full communication of these expectations and a more rigorous enforcement machinery started to take effect. Future clients can, of course, make sure that these mechanisms are contractually embedded from the start, including full transparency in bidders’ submissions of the additional costs allocated in order to comply with PAYE direct employment, NWRA benchmark terms and conditions, living wages etc.

As an additional measure, clients might also want to consider imposing commercial sanctions when Tier 1 contractors fail to comply with contractual minimum employment standards or allow subcontractors and labour suppliers to flout them. These sanctions should be calibrated to exceed any cost savings that might otherwise have been gained from undercutting NWRA terms and conditions and/or avoiding PAYE and national insurance contributions.

Recommendation 3: Even where a major-project client opts not to enter into a project-wide agreement with trade unions, it should still give serious consideration to the significant advantages, both tangible and intangible, of establishing contractually-binding minimum employment standards, such as PAYE direct employment and alignment with NWRA minimum benchmark terms and conditions. In designing contractual requirements, clients should:

a) Reject unsubstantiated advice that their preferred minimum employment standards may not lawfully be incorporated into contracts, and explore the new potential flexibilities created by recent changes to EU and UK public procurement law;

b) Describe their expectations as clearly and comprehensively as possible, ideally as part of an ER code of practice incorporated into each Tier 1 contract;

c) Make the additional costs associated with compliance with minimum employment standards transparent. Define the process to be adopted when it is genuinely impracticable for a Tier 1 contractor or part of its supply chain to comply with one or other aspect of minimum employment standards;

d) Consider imposing sanctions for non-compliance with minimum employment standards, set at an appropriate level to dis-incentivise such behaviour.

Establishing effective ER coordination processes

From a purely legalistic perspective, since each Tier 1 contractor carried almost all responsibility and risk for ER under the contract, Crossrail could have taken the view that it had little reason to concern itself with how well or how badly the contractor was discharging this responsibility. In practice, however, as ER issues on the project started to emerge during 2012, Crossrail felt compelled to intervene, but at first without either sufficient information or other mechanisms to act effectively. Tier 1 contractors too, having carefully guarded their autonomy in the early days, began to request more sharing of information and an enhanced role for the client as guarantor of some measure of consistency and good ER practice across the project.

This change of heart led ultimately to the replication of key elements of the Olympic Park ER coordination regime. Crossrail’s experience has therefore fully reconfirmed the importance of effective ER coordination processes on construction major projects. Ideally, of course, on future projects these processes should be in place from the outset, embodied within a contractually incorporated ER code of practice, and operated under the supervision of one or more client ER specialists. Table 1 below outlines the key similarities and differences between measures adopted on Crossrail and previously on the Olympic Park.

Table 1 – Comparison of client ER regimes on the London 2012 Olympic Park (2008-11) and Crossrail (2011-18). [C] = Tier 1 contractual obligation, [NC] = no Tier 1 contractual obligation

Measures Olympic Park Crossrail Code of Practice

Detailed ODA code of practice covering both substantive and procedural requirements and incorporated into all Tier 1 contracts. [C]

Similar code developed only later and by agreement, covering procedural requirements only. [NC] Procurement Detailed ER questionnaire included in code of practice, to test bidders’ ER resources and understanding during procurement of both Tier 1 contracts and subcontracts. [C]

No similar questionnaire for Tier 1 procurement on Crossrail, although from early 2013 Crossrail Head of ER interviewed preferred bidders on remaining major Tier 1 contracts, and Tier 1s encouraged to carry out similar checks of prospective subcontractors on a voluntary basis. [NC]

Reporting

Tier 1 ER reports, submitted monthly. [C]

Similar Tier 1 reports, submitted every 8 weeks [NC] Information and coordination meetings

Monthly meeting, chaired by client and attended by all Tier 1 ER leads [C] Equivalent monthly meeting. [NC] Performance reviews

Regular contract-level meetings, attended by client and Tier 1 project managers, as well as respective ER personnel. [NC]

Similar meetings, held as part of a more formalised ER performance assurance framework process. [NC] Payroll audits

Regular audits of Tier 1 and subcontractor employers’ compliance with MoA minimum employment standards. Audits of subcontractors initially carried out by client directly, but responsibility then increasingly handed over to Tier 1s. [C]

Similar audits of employers’ compliance with LLW and ETI Base Code minimum employment standards. Responsibility for subcontractor audits assigned to Tier 1s from the outset, although coverage, quality and outcomes of Tier 1 audits checked as part of performance assurance process. Occasional direct audits of Tier 2 labour suppliers by client cost verification team, especially during tunnelling phase of project. [NC]

Helpline

Dedicated confidential workforce concerns helpline provided by client. Cases referred on to relevant Tier 1 for investigation and report back. [NC]

Confidential workforce complaints received via client’s public helpline, rather than dedicated concerns service. Referral and report back process similar to Olympic Park. [NC]

Risk management

Client kept main ER risks under review as part of its own formal risk management process.

ER risks kept under review in similar way by client. Performance assurance process used to encourage Tier 1s to manage ER risks more systematically as well.

Executive level involvement

ER matters one of the topics covered in regular exchanges between client and Tier 1 executives. Specific performance concerns escalated to client Programme Director and/or Construction Director where necessary.

Similar level of involvement, with client Delivery Director and/or Programme Director taking lead in resolving concerns requiring escalation. Intermediate level involvement

Regular contacts (both formal and informal) between ER specialists, project managers and other relevant functions (e.g., health and safety, security, employment and skills, legal, procurement and commercial).

Similar level of contact. Client Head of ER attended weekly meeting between Delivery Director and direct reports. Trade union liaison

Thrice-yearly information sharing meetings involving client Construction Director, Programme Director and ER lead, and senior representatives from all four (subsequently three) construction trade unions: one General Secretary and three national officers.

Similar meetings, also arranged thrice yearly. Client represented by Delivery Director, Talent and Resources Director and Head of ER. London-based local officials represented all three (subsequently two) remaining construction trade unions.

Demonstrations and disputes

Off-site demonstrations managed centrally by ODA’s Park logistics and security team.

Contractors required under ER code of practice to keep ODA advised of any significant disputes and to attempt to resolve issues through NWRA procedures.

Off-site demonstrations managed at contract-level by Tier 1 contractor(s) affected. Notification procedure operated by client to advise site teams and external stakeholders (e.g., Transport for London) about any anticipated demonstrations.

ER code of practice asked Tier 1 contractors to keep Crossrail advised of any significant disputes, and encouraged resolution of disputes through grievance procedures, applicable NWRA procedures and/or ACAS. [NC]

One question that remains is whether the main innovation adopted on Crossrail – the ER PAF [previously discussed above] – represents a valid new addition to the established suite of ER coordination processes above. This is certainly possible. Although it is true that one of the main reasons for extending the PAF to ER was to compensate for gaps in Crossrails contractual ER requirements (i.e., by encouraging contractors to go beyond mere contractual compliance), it is still conceivable, even on future contracts with more comprehensive ER provisions, that a client may wish to make differences in contractors’ performance visible, particularly if shortcomings on one or more contracts are starting to give cause for concern. A PAF can also perform a valuable function in promoting innovation and healthy competition among contractors. One further development, never attempted on Crossrail, could be to introduce a system of visible recognition and reward for those Tier 1 contractors, and even subcontractors, whose initiatives in the field of ER surpass both standard industry practice and those of their peers.

Recommendation 4: In order to support effective contractor management of ER, and information sharing and coordination between contractors, clients on major projects should develop an ER code of practice and incorporate this into their contracts. In developing its code, the client should consider:

a) Including the full range of coordination processes established on previous projects;

b) Adding a PAF-style active performance management process and possibly a system of recognition and reward for outstanding and innovative ER practice.

Strengthening organisational ER capabilities

Both Crossrail and its Tier 1 contractors initially faced challenges in developing the right levels of organisational

capability to deal appropriately with the special ER circumstances of a construction major project.

As a client, Crossrail was not the first to face challenges of this sort, which stem from commonly held misconceptions (a) that ER is not a strategic concern for construction clients (unlike health and safety, community relations or employment and skills, for example), and (b) that establishing a strong client ER function necessarily takes the client down a “slippery slope” towards managing supply chain ER problems directly. Experience on Crossrail and earlier major projects has demonstrated that such fears need not be realised, and that the potential distraction and drain on senior executive resources in the absence of an effective ER function, should make its establishment an early priority. To be effective, this function should be actively involved from the earliest days of the project in:

- Designing the client’s overall ER strategy, including confirming a position on direct trade union engagement;

- Inputting into the drafting of relevant contractual provisions;

- Developing an ER code of practice to be incorporated into the contract; and

- During procurement, scrutinising bidders’ understanding, capability and willingness to manage ER in a major-project environment

Another lesson learned from the Crossrail experience is the importance of locating the ER function appropriately within the organisational structure. A consistent pattern on CTRL, T5, the Olympic Park and (from 2013) Crossrail has been for ER to report directly to one or more members of senior executive management. Typically this has been the most senior one or two executives responsible for construction delivery, although on Crossrail the head of ER from 2013 had a dual reporting line to both the Programme and Talent and Resources Directors. Except on projects where ER risks are genuinely of a lower order, this level of seniority is necessary in order to guarantee an appropriate speed of response – major ER issues having the potential to escalate very quickly – and to assist the ER function overcome any internal resistance to implementation a proactive ER strategy (which, as already explained, will be unfamiliar and even threatening to many people’s long-held preconceptions about the limits of a client’s role). Having capitalised on this endorsement from the top, it will of course then be up to the ER function itself to build understanding, cooperation and mutual trust with colleagues from a range of disciplines and backgrounds, including (in particular) project managers, procurement and commercial specialists, health and safety, security, logistics, legal and external affairs. Given most UK construction professionals’ lack of experience and understanding of a challenging ER environment, this is likely to involve some degree of early awareness-raising training, and regular reinforcement of key good-practice messages after that.

Similar issues of organisational capability will apply to Tier 1 contractors. Whilst many of the Tier 1 ER specialists who worked on the Crossrail project were of a high calibre, this was not always the case, and, even where a competent ER lead was in place, this did not always mean that their advice was listened to or acted upon. Clients on future major projects should take care to mandate the allocation of a suitably qualified and experienced Tier 1 ER lead on every contract, with sufficient time, resources and organisational support to perform the job properly. Given the shortage of such in-house expertise among many Tier 1 contractors, this may in some cases involve recruiting an experienced ER practitioner from outside the construction sector and/or developing an existing employee from a different, albeit possibly related, disciplinary background. In addition, each Tier 1 contractor or joint venture should be required to nominate a senior executive manager to hold ultimate accountability for ER contractual compliance and good practice on its contract(s). In the event of persistent under-performance, this manager would be answerable to the client’s ER executive lead.

Whilst some aspects of Crossrail’s ER contractual requirements needed enhancing later on, the insistence that each Tier 1 contractor must develop its own ER policy was proved a useful innovation since this helped reinforce contractors’ responsibility and ownership of ER management – something that arguably was sometimes obscured or forgotten on T5 and the Olympic Park. In future, clients’ ER codes of practice should specify in greater detail the expected scope, content and quality of such a policy. Bidders should be required to provide a draft policy for critical scrutiny during the procurement process, and to submit a finalised policy for amendment and approval on award. Once work is under way, Tier 1 contractors should be judged on how robustly ad consistently they are implementing their ER policy, and be encouraged to keep it under review, making improvements and updates as and when required. In addition, the client should consider using a PAF process and/or recognition-and-reward scheme to promote particular exemplars to other Tier 1 contractors on the project, or even further afield.

Recommendation 5: Clients on major projects should take steps to maximise the ER capabilities of both their own organisation and those of their Tier 1 contractors. These should include:

a) Appointing a suitably qualified and experienced client ER lead as early as possible, who will play an active role in shaping key aspects of the ER regime for the project, including the overall strategy, contractual provisions and an ER code of practice, and participating in the procurement process;

b) Ensuring the ER function is appropriately positioned within the client organisation, including one or more direct reporting lines to the senior executive leadership team;

c) Mandating the appointment of a suitably qualified, experienced and resourced Tier 1 ER lead, and the nomination of a Tier 1 senior executive manager to hold ultimate accountability for ER performance;

d) Insisting that each Tier 1 contractor develops and implements a comprehensive and robust ER policy, which is kept under regular review.

e) Seeking to address current gaps in ER capability and understanding, including ongoing ER training and awareness raising for key professional/ managerial personnel, and enhancement of Tier 1 contractors’ own in-house ER capability, whether through external recruitment, internal development or a combination of both.

Prioritising any wider ER ambitions

Construction is not generally regarded as a sector that exemplifies good ER practice.[19] In large part, this is a structural problem, related to high commercial and financial risks, low profit margins, over-use of subcontracting, false “self-employment”, low levels of investment and innovation, and supervisors and managers who are often inadequately trained and supported. These same structural issues also contribute to wider performance shortcomings in key areas such as productivity and quality.[20]

Although Crossrail attempted to interest Tier 1 contractors in addressing such issues through certain “value-added” and “world-class” sections of the ER PAF (outlined above), these efforts proved mostly too little, too late. Future clients should consider right at the outset what level of ambition they have to tackle long-standing weaknesses in industry performance, and how they might go about doing so to the greatest effect. Some possible themes are highlighted in Recommendation 6, below.

Recommendation 6: Major-project clients have an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in tackling long-term structural weaknesses in contractors’ management of ER, and through these some of the factors underlying the industry’s persistent under-performance in relation to productivity and quality. Any such ambitions will need to be prioritised, however. Possible areas of focus might include:

a) Discouraging over-reliance on subcontracting (for example, by restricting the number of subcontracting tiers);

b) Encouraging Tier 1 contractors to frame ER issues not just as risks, but also as potential opportunities;

c) Supporting Tier 1 contractors and subcontractors to adopt minimum employment standards not just on one project, but more widely;

d) Encouraging innovations in workforce and/or trade union engagement, and measuring any positive impacts with regard to safety, productivity and/or quality performance;

e) Promoting closer collaboration between Tier 1 contractors and subcontractors to spread good practice and raise standards;

f) Spreading the message about the value of good ER practice and positive client involvement to other clients and Government and support steps to eradicate bad practice, including false “self-employment”.

References

[1] Eldred, A. (2015), Inside the Hollowed-Out Firm: Regulating Employment in Two Construction Supply Chains – University of Birkbeck MSc dissertation (unpublished).

[2] Deakin, S. and Koukiadaki, A. (2009), Governance Processes, Labour-Management Partnership and Employee Voice in the Construction of Heathrow Terminal 5, Industrial Law Journal, 38(4).

[3] Eldred, A. (2012), Olympic Park Industrial Relations: the Memorandum of Agreement – Olympic Delivery Authority (available at http://learninglegacy.independent.gov.uk/publications/olympic-park-industrial-relations-the-memorandum-of-agre.php).

[4] Druker, J. and White, G. (2013), Employment Relations on Major Construction Projects: the London 2012 Olympic Construction Site, Industrial Relations Journal, 44(5-6).

[5] ONS (2017), Labour Disputes in the UK 2016 – Office for National Statistics (available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/workplacedisputesandworkingconditions/articles/labourdisputes/latest#industrial-analyses).

[6] Druker, J. (2007), Industrial Relations and the Management of Risk in the Construction Industry, in A. Dainty, S. Green and B. Bagilhole, eds., People and Culture in Construction: A Reader – Abingdon, Taylor & Francis.

[7] Elliott, J. (2014), The Umbrella Company Con-Trick – UCATT (available from: https://www.ucatt.org.uk/files/publications/141023%20Umbrella%20Company%20Con-Trick%20Report.pdf).

[8] Fisher, J. (1993), Industrial Relations and the Construction of the Channel Tunnel, Industrial Relations Journal 24(3).

[9] Lakhani, T., Kuruvilla, S. and Avgar, A. (2013), From the Firm to the Network: Global Value Chains and Employment Relations Theory, British Journal of Industrial Relations 51(3).

[10] Donaghey, J., Reinecke, J., Niforou, C. and Lawson, B. (2014), From Employment Relations to Consumption Relations: Balancing Labour Governance in Global Supply Chains, Human Resource Management Journal 53(2).

[11] Marchington, M., Grimshaw, D., Rubery, J. and Willmott, H., eds. (2005), Fragmenting Work: Blurring Organizational Boundaries and Disordering Hierarchies – Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[12] Marchington, M. and Vincent, S. (2004), Analysing the Influence of Institutional, Organizational and Interpersonal Forces in Shaping Inter-Organizational Relations, Journal of Management Studies 41(6).

[13] Purcell, J. (1999), Best Practice and Best Fit: Chimera or Cul-de-Sac?, Human Resource Management Journal 9(3).

[14] Korczynski, M. (1996), The Low-Trust Route to Economic Development: Inter-Firm Relations in the UK Engineering Construction Industry in the 1980s and 1990s, Journal of Management Studies 33(6).

[15] Marsden, D. (1999), A Theory of Employment Systems: Micro-Foundations of Societal Diversity – Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[16] Latham, G. (2012), Work Motivation: History, Theory, Research and Practice – Los Angeles, Sage.

[17] The main National Working Rule Agreements applicable to different sectors include: the Construction Industry Joint Council (CIJC), covering civil and building workers; the Joint Industry Board for the Electrical Contracting Industry (JIB), covering electricians in England, Wales and Northern Ireland; the Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Agreement (HVACR), covering mechanical trade operatives; and, the National Agreement for the Engineering Construction Industry (NAECI), covering engineering construction workers. In addition, there are a separate Scottish electrical agreement (SJIB) and two plumbing agreements (JIB-PMES and SNIJIB), although the latter two tend not to be used so much on major infrastructure projects.

[18] Behling, F. and Harvey, M. (2015), The Evolution of False Self-Employment in the British Construction Industry: A Neo-Polanyian Account of Labour Market Formation, Work Employment and Society, 29(6).

[19] Dainty, A., Green, S. and Bagilhole, B. eds. (2007), People and Culture in Construction: A Reader – Abingdon, Taylor & Francis.

[20] Farmer, M. (2016), The Farmer Review of the Construction Labour Model: Modernise or Die – Construction Leadership Council.

-

Authors

Andrew Eldred MA, MSc - Crossrail Ltd

Andrew Eldred was Head of Employee Relations at Crossrail until early 2017. His responsibilities included trade union engagement, oversight of contractors’ management of site employment relations, and delivery of apprenticeships and other skills and employment commitments. Before joining the Crossrail programme, Andrew held several senior employment relations roles in construction, including three-and-a-half years as the ODA Delivery Partner’s Industrial Relations Manager on the London 2012 Olympic Park construction programme. He holds an MA in Modern History from the University of Oxford and an MSc in Human Resource Management from Birkbeck College, London.

-

Peer Reviewers

Professor Geoffrey White. Professor of HRM, University of Greenwich Business School

David Newborough CIPD FRSA, Senior Advisor/NED (Former HR Director E.ON UK)