Fatigue Management

Document

type: Technical Paper

Author:

Christina Butterworth RN, SCPHN, Hon.FFOM

Publication

Date: 13/03/2018

-

Abstract

Fatigue has the potential to have a significant impact on safety, performance and health. In the construction industry fatigue management focuses on the risks associated with shiftwork, rather than a whole system approach which includes the environment in which its staff live and work and the individual susceptibility. Following a review of the research on fatigue and good practice used in the construction and other high risk industries a toolkit was developed. Providing a set of benchmarks to create a step change in fatigue management in the construction industry.

This paper will be of benefit to all major projects looking to implement a fatigue management programme. -

Read the full document

1.0 Introduction

Industry recognises the importance of the management of fatigue risk at work as part of its general responsibilities under health and safety legislation (e.g. Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (1999))[1] and with reference to the Working Time Regulations 1998[2].

Therefore a proposal was presented to the Crossrail Health and Safety Committee to review the evidence base and develop a greater understanding of what good practice in fatigue management at work entails and was agreed.

To start the process a construction and transport industry overview was carried out to create a better understanding of the impact of fatigue to try and identify what measures could be employed to mitigate the risk within the Crossrail programme. This was followed by a detailed look at the science behind fatigue and why and how fatigue impacts on individuals.

On completion of the study it was felt that Crossrail would be better placed to create more informed, targeted policies and procedures to try and deal with the fatigue risk factors identified within the programme.

Given the wealth of research available, a pragmatic approach was taken to improve fatigue management by adopting and adapting best practice where possible and incorporating this into a toolkit for use by Crossrail and its Principal Contractors.2.0 Industry Review

2.1 UK PLC

Lack of sleep is having a significant impact on the health and productivity of the working population and has a cost to the economy. RAND Europe’s recent research[3] calculated that a person who sleeps, on average, fewer than six hours a night has a 13% higher mortality risk than someone sleeping between seven and nine hours, (described as the “healthy daily sleep range”). Costs to the economy have been estimated at £40billion and just over 200,000 lost working days a year, including absenteeism and presenteeism (working at sub-optimal levels). RAND Europe has suggested that simple changes such as an increase in sleep to between six and seven hours per night could add £24 billion to the UK economy, with other interventions increasing this figure further.

Business needs to manage its operational requirements through the use of flexible working and various shift patterns and provide help for workers to balance their responsibilities at work and home, in a 24-hour society.

Research in the rail, aviation, construction industries and occupational medicine has shown that shiftwork is known to cause a significant risk due to the impact on sleep and fatigue.2.2 Driver Tiredness

Research on drivers[4] has shown that driver fatigue contributes to 20%-30% of all private vehicle deaths and severe injuries. A driver awake for 17 hours is performing at a similar rate to a driver with a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.05% and after 21 hours similar to someone with a BAC of 0.15% (the legal driving limit is 0.08% in England and 0.05% in Scotland).

A study on bus drivers[5] found that of those with an Epworth sleepiness[6] score of 10 (indicative of excessive daytime sleepiness or a sleep disorder); 8% had fallen asleep at the wheel in the past month; 18% reported a near miss; and 7% had had an actual accident due to sleepiness while working.2.3 Rail industry

Fatigue is thought to account for 20% of rail accidents[7,8]. There have been a number of research projects carried out by the RSSB[9], which form the basis of a White Paper. In summary the research showed:

- The overly simplistic use and interpretation of the HSE Fatigue Risk Indicator, due to lack of training

- Contractualised nature of the rail industry being a challenge

- Measures required to reduce the risk related to fatigue that can be experienced during first night shifts

- Long hours culture – ‘always on’

- Both home-life and work-life related factors contributed to fatigue at work.

- The impacts of the use of biomathematical models to determine risk vary depending on industry needs

The key findings and recommendations were:

- The benefits of healthy napping and other countermeasures such as healthy caffeine intake

- Need to reduce monotonous and detailed work during first night shifts

- Sleeping 3 to 4 hours before first night shift help mitigate any initial sleep debt

- Journey management – if exceeding 1.5 hours before start of shift, alternative arrangements should be made in the form of transportation or lodgings

- Use of bright light in break areas to help with affect on circadian rhythm

- Rest for 15 minutes every 4 hours for restoration.

- Further research needed to assess the impact of hours of work on sleep, fatigue and performance and subsequent shift patterns

- Need to establish criteria for fitness for duty checks

A review of fatigue and rail accidents carried out by the RAIB[10] found that rostering was still based on working time limits, with all the expected measures, monitoring and controls in place, such as; using the fatigue risk calculator as an indicator and the use of mapping rosters. Control measures such a training and site briefings, fitness for duty, reporting of sleep disorders and ongoing reporting and feedback from front line staff were in place but not fully implemented.

2.4 Airline industry

Shift optimisation was considered an issue in the airline industry, due in part to roster disruption. Rules of flying were adhered to, but still required self-awareness of personal fatigue and accurate reporting though the Aircraft Communication Addressing and Reporting System, with some issues of trust and understanding of the use of Karolinska Sleepiness Scale[11,12].

2.5 General Factors

There was a need to recognise the ‘lived reality’ of a 24 hour society, the cumulative effect of fatigue, the importance of energy intake from food, the affects of the first and to a lesser extent the second night of shiftwork and the impact on home life (rest and recovery day, impact of fatigue on family).

This review confirmed that industry has been addressing the risk associated with fatigue but has not yet developed a fatigue management programme that addresses all aspects of fatigue management at work I,e, encompassing the person, the work and the environment.

The next step was to investigate the scientific effects of fatigue on individuals.

This would then provide the complete background information for the Crossrail Occupational Health team to start developing a tailored approach to fatigue.3.0 Fatigue management at work

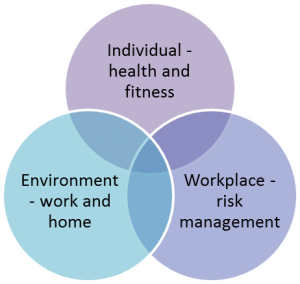

An integrated programme that encompasses the health and fitness of the workers, the health risks inherent in the workplace and how they are managed and the work and home environment is required to reduce the impact of fatigue on the individual and the business.

Figure 1 – Fatigue Management

3.1 Individual factors

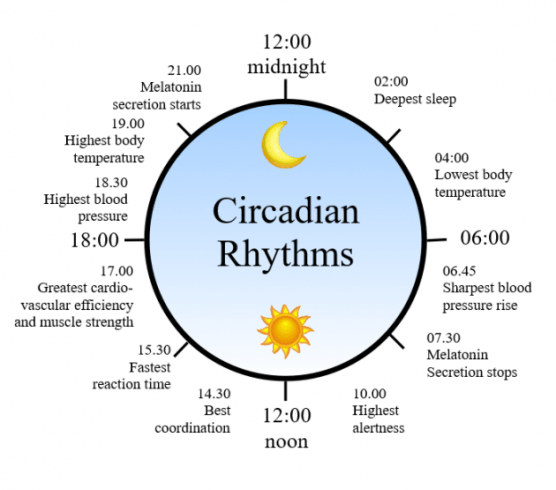

There are three key drivers for health and fitness for work that are directly linked to fatigue. These are the Circadian rhythm, health impacts and lifestyle. The impact of each of these elements are outlined below:

3.1.1 Circadian rhythm

The circadian rhythm is the in-built body clock, which is associated with sleep, body temperature, melatonin and cortisol. The circadian cycle and time awake have the most significant effect on sleepiness, mood and attention. Logical reasoning is not affected by lack of sleep, rather it is higher executive functions such as risk taking, verbal fluency and visual vigilance that are affected. This will have an impact on attention, communication, planning, verbal fluency, dealing with the unexpected and grasping & updating ‘the big picture’. When an individual is sleep deprived, their decisions become influenced by emotions with limited self-insight, resulting in either distorted optimism or risk aversion. Recovery of the higher executive functions needs deep sleep.

Research has shown that most workers on permanent or long-term night shift do not adapt their circadian rhythm to the new work schedule[13].Healthy napping[14] can be used to alleviate sleepiness and manage any sleep debt occasionally, though it is not effective on restoring executive functioning. Healthy napping can be used prior to the first night shift to reduce the time awake and used in conjunction with caffeine to provide up to an additional 2 hours or work ability in exceptional circumstances. If napping is allowed during the shift it needs to managed appropriately so that the time between sleep and fully waking is taken into consideration, as it can take 15-30 minutes to recover from this sleep inertia. In general however, caffeine can negatively affect sleep quality.

The use of ambient blue enriched light is good for staying awake and brief exposure to bright light improves cognition and alertness. It is not however, possible to determine the duration of its effect and further research is required.3.1.2 Health impacts

There are a number of health conditions that are directly and indirectly associated with sleep loss. The three main health conditions that directly affect performance at work and increase the risk of a significant event are; obstructive sleep apnoea, shiftwork sleep disorder and insomnia. Most of the health assessments carried out at Crossrail, as part of the fitness for work medical assessments, focused on night work and identification of chronic health conditions that may be affected by nightwork, rather than exploring the shift patterns, symptoms of sleep loss/poor quality sleep and opportunity for healthy sleep.

Hult International Business School conducted research on how sleep loss affects the lives of working professionals[15], due to the mounting evidence of this ‘hidden threat’ to industry. The effects related to; performance, physical health and social and emotional life and were evident across all levels of the organisation. It demonstrated a relationship between chronic sleep loss and health conditions including; cardiovascular disease, obesity and type 2 diabetes and concluded that there was an important association between health and sleep.

Health assessment standards in the construction industry are based broadly on the DVLA medical fitness to drive, section 92 of Road traffic Act[16], which requires individuals to notify the DVLA of any prescribed (epilepsy, visual impairment, obstructive sleep apnoea), relevant (blackout) or prospective (Type 1 diabetes) disability. Doctors and other healthcare professionals are required to notify the DVLA when fitness to drive requires notification, but individuals cannot or do not notify the DVLA themselves. The implications being that these conditions could result in:

• Risk of a sudden and disabling event

• A medical condition likely to render the person at risk of danger when driving

• A request for a medical opinion on the impact of multiple conditions3.1.3 Lifestyle – diet, alcohol and drugs, strenuous activities

Lifestyle factors can affect both sleep quality and quantity and thereby contribute to sleepiness. These include:

• Diet – changing meal times to coincide with shifts can affect the gastrointestinal system, as well as the availability of good food choices.

• Food is directly linked to energy and blood sugar levels.

• Stimulant and sedatives – stimulants such as caffiene, chocolate and nicotine can increase restlessness, disrupt normal sleep and cause gastro-intestinal disturbances. Sedatives such as alcohol and sleeping pills can induce sleep but the effects are short lived and may increase risk of dependence.

• Strenuous activities – can help deepen sleep and induce sleep earlier. However, strenuous exercise before sleep is not recommended as it raises temperature for up to five hours which affects the circadian rhythm.3.2 Work related factors

Humans are a diurnal species and would normally sleep at night. Working shifts disrupts the natural sleep wake cycle, with the greatest effects felt during long shifts over 10 hours, rapid turnaround of shifts, long work weeks over 60 hours and shifts that incorporate the circadian nadir of 3am-6am. When managing shift work there are three issues that need addressing:

- Shift timing

- In terms of recovery time 12 hours rest usually results in 6 hours sleep, so avoid shifts that do not allow for 12 hours rest.

- If shifts are scheduled to start at 6am the operatives are likely to have had 6 hours sleep, 8am start more than6hours and 10am start more than8hours sleep.

- Use evening shifts for recovery – employees are likely to get more sleep, as they do not schedule other social activities.

- Forward rotating shifts with 2 days rest are the least harmful.

- Schedule rest breaks

2. Shift length

- Increasing shift length from 8-12 hours can double the risk of an accident

- Ideally employees should be awake for a maximum of 16 hours each day and work no more than 60 hours per week

- The number of consecutive work days should be not more than 6 (dependent of other responsibilities, commute and eating etc.)

- Excessive working hours (overtime, on-call rotas, additional jobs) should be avoided

3. Type of work

- both work intensity and the task itself can affect fatigue

- Work that is physically or mentally strenuous will impact the individual

- Monotony of task has a direct impact on the feeling of tiredness

In addition to the shiftwork factors outlined above, research from healthcare provider Simplyhealth[17] shows that around four million workers never take a full lunch break and about 12 million eat at their desks or on the go.

Also research from Birkbeck University of London and University of Bedfordshire , reported by the British Psychological Society, demonstrates that fewer than half of UK organisations provide employees with guidance on how to switch off from work when they go home[18].3.3 Environmental factors

Environmental factors are a joint responsibility of the employer and the employee as both the home and work environments can affect fatigue. The work environment elements are:

- Temperature – any extreme of temperature can be tiring

- Noise and vibration – high levels cause physical and mental fatigue

- Lighting – dim lights induce sleep and bright lights increase wakefulness

- Work demands – intensity over long periods of time, monotonous tasks, complex tasks at start of first night shift, adequate handover

- Comfort – ergonomic factors such as seating, desk adaptability,working environment

The home environment elements are:

- Maximising opportunity for sleep – bedtime routine, minimising impact of social commitments

- Preparing for sleep – controlling temperature, sound and light to induce and prolong sleep

- Living arrangements – multiple occupancy accommodation, long commute, affordable accommodation

4.0 Crossrail Fatigue Management

Given the research available, Crossrail recognised that fatigue could impact on its workforce and that it should be proactively managed by establishing a Fatigue Policy and Fatigue Management Plan across the project. In addition, as shift patterns were a key factor, it was decided to conduct some research on shiftwork and fatigue with sponsors TfL.

4.1 TfL Shift Pattern Study at Crossrail

TfL conducted a study on three rotating shift patterns used on Crossrail to assess the impact on fatigue. This was a non-experimental field study, taking objectives measures from wearable technology and correlating this data with subjective data from a range of questionnaires. The study focused on average sleep length, time to sleep and quality of sleep.

The three shift patterns identified were as follows:- DLN – 7D3R7N2R7L2R

This consists of seven day shifts (7am-3.45pm), three days rest, seven night shifts (10pm-7.45am) two rest days, 7 late shifts (3pm-10.30pm) and two days rest. - 5252 – 5D2R5N2R

This consists of five-day shifts (7am-7pm), two rest days, five night shifts (7pm–7am) and three rest days - 7473 – 7D4R7N3R

This consists of seven-day shifts (7am-7pm), four rest days, seven night shifts (7pm-7am) and three rest days.

Findings of the study demonstrated that one shift pattern was significantly worse than the others in terms of fatigue risk and cognitive effectiveness; the Day Late Night shift (DLN-7D3R7N2R7L2R).

Though this shift had the shortest working days, it had the greatest impact on fatigue, which contradicts logic/good practice identified by the HSE,(see ref 19), but may demonstrate the need for workers to get adequate sleep before starting night shifts.

All shift workers on the night shifts were not getting enough sleep and either started with a “sleep debt” before the first night shift due to lack of adequate sleep or built up a “sleep debt” on subsequent nights. There were also significant differences on cognitive effectiveness levels, as identified by the use of questionnaires, particularly on night shifts.

Recommendations were made to reduce the number of consecutive working nights to a maximum of 3 or 4 or consider other rostering options, and to gather more data on shift patterns and mitigations.

As a result of the study a number of Crossrail sites have changed their rostering patterns to allow for the impact of fatigue on the first night shift and on nights 4 and beyond, to good effect.

Follow up studies were conducted to assess the impact of shift work and the effectiveness of a number of interventions. Using a combination of fatigue questionnaires, wearable technology, (to track fatigue indicators), fatigue awareness sessions and feedback, the studies were able to identify high-risk shift patterns and high-risk personnel.

Fatigue data was gathered for 30 days initially and then participants were provided with a personal mobile app enabling them to view their fatigue scores, which resulted in an average increase of sleep of 27 minutes per night and a reduction of fatigue exposure by 24%. The supervisors were provided with a real-time electronic dashboard device to monitor fatigue of staff and provided with information on a number of interventions, such as; referral to occupational health or re-assignment of duties. Fatigue Science[19] was the technology used but other providers can offer similar technology applications.

The research also identified at least one member of staff with undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea and provided information that enabled several members of staff to change their sleeping habits and get the recommended amount of sleep to perform effectively every day.4.2 Site Visits and Health Audits

Occupational health audits and site visits continued to highlight fatigue as one of the key health risks. This was primarily due to the impact of the schedule becoming more complex and compressed towards the final stages.

The improved engagement with the workforce also highlighted the health effects of fatigue.4.3 Measures To Address Fatigue

The Crossrail Fatigue Policy demonstrates commitment to managing fatigue and is supported by a Fatigue Management Plan, which provides information on managing fatigue risk and reducing the likelihood of work related incidents associated with shiftwork, including the use of the HSE Fatigue and Risk Index[20]. These requirements were incorporated in the contractual requirements for all Principal Contractors.

The Fatigue and Risk Index provides an overall assessment of the risk associated with fatigue in any shift pattern, using five main factors that impact on fatigue:

• shift start time

• shift duration

• length of time between duties

• breaks within duties

• number of consecutive shiftsIt is particularly useful when comparing different shift patterns, or when proposing new patterns of working, and when reviewing operational practice.

Fatigue risk management plans were put into place by contracts on individual sites, along with the provision of information and training and monitoring arrangements. Most of the risk assessments focused on the management of shift work hours. They were mainly task based risk assessments, with a few individual risk assessments for those identified as high risk. Monitoring arrangements focused on exceedance of hours worked outside of maximum hours limits set by each contractor and were primarily linked to payroll and cost management, or arbitrarily accepted as exceptional business requirements.4.3.1 Fatigue management toolkit

A fatigue toolkit was developed to raise awareness, to change attitudes and behaviours towards fatigue management. It supports the assessment of risk and monitoring fatigue for health effects. It does not address any formal methods to include fatigue as a root cause of accidents and incidents.

The toolkit consists of good practice already available and new materials to help manage fatigue in the workplace, including:- Fatigue awareness training for supervisor

- Fatigue awareness training for staff

- Fatigue risk assessment template

- General risk reduction measures

- Task based risk assessment

- Individual risk assessment

- Monitoring checklist

- Fatigue indicators for incident investigation

- ORR Good practice guidelines; Fatigue Factors and Managing Rail Staff Fatigue

- HSE Managing Fatigue Risk

The follow-up from providing the toolkit would be to identify the impact of fatigue monitored through various performance measures.

5.0 Lessons Learned

The fatigue management plan focused on shift work and did not explicitly address other human factors. Given the research identified this could have been expanded.

Research is available on the impact of fatigue on performance and the use of wearable technology was effective in assessing the risks and the positive impact of various interventions.

More work is needed on assessing fitness for work in relation to sleep disorders.

There were no formal methods to include fatigue as a root cause of accidents and incidents. Fatigue risk factors should be incorporated into incident reporting and investigation processes.

An assessment of the ‘lived reality’, which takes into consideration the individual and work environment factors, would demonstrate the effectiveness of implementation. Any such review should involve workers, supervisors, safety, occupational health and management.6.0 Conclusion

The research conducted on Crossrail resulted in a reduction in risk associated with different shift patterns. It has also led to the development and implementation of a range of interventions to reduce fatigue risk.

The toolkit now available should drive a step change in the management of fatigue but monitoring and further research would be required to determine the impact.7.0 Recommendations for Future Projects

A fatigue management programme should include the three main elements; worker, work and the environment in which they live and work.

The construction industry needs to act together to manage fatigue in order to tackle a culture that addresses management of worker fatigue only in the short term, and manages its workload through long hours within pay structures already supporting this.

If possible, gather data to inform any fatigue risk management programme through:- Research on shift patterns and interventions using wearable technology

- Review of incidents reported on the in-house system to determine the impact of fatigue as a root cause

- Assessment of the effectiveness of training on changing behaviour

- If using a toolkit, ensure feedback is gathered on its use

Investigation of incidents should include information on fatigue, irrespective of whether fatigue is judged to be a root cause at the time. The data collected should include: the timing of the shift, timing of breaks taken, previous shift pattern, immediate sleep history, commuting time, a fatigue checklist including specific symptoms (unintentional closing of eyelids, problems completing tasks, becoming easily distracted) as well as environmental factors (temperature, lighting).

8.0 References

[1] UK Government legislation, (1999), “The Management of Health and Safety at work regulations 1999”. [Online], available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1999/3242/contents/made. Accessed on 23 October 2017.

[2] UK Government legislation, (1998), “ The Working Time Regulations 1998. [Online], available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1998/1833/contents/made . Accessed on 23 October 2017.

[3] Hafner, Marco, Martin Stepanek, Jirka Taylor, Wendy M. Troxel and Christian Van Stolk. Why sleep matters: The economic costs of insufficient sleep. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9962.html . Accessed 30 August 2017.

[4] Jim Horne and Louise Reyner, Sleep Related Vehicle Accidents, Sleep Research

Laboratory, Loughborough University, 2000[5] Vennelle M, Engleman HM, Douglas NJ Sleep Breath (2010) “Sleepiness and sleep-related accidents in commercial bus drivers” Feb 2010 Volume 14 Issue 1 pp39-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-009-0277-z

[6] The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. [Online] available at: http://epworthsleepinessscale.com/about-the-ess/ . Accessed 23 October 2017.

[7] Office of Rail Regulation Guidance (2012), “Managing Rail Staff Fatigue”.

[8] Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) (February 2015), “Fatigue and its contribution to rail incidents: special topic report”. [Online], Available at: https://www.rssb.co.uk/pages/search-results.aspx#!#k=FAtigue%20and%20its%20contribution%20to%20Rail%20Incidents. Accessed 30 August 2017.

[9] Research in brief – RSSB series 2016; Research into fitness for duty checks and predicating the likelihood of experiencing fatigue T1082, Preparing the rail industry guidance on bio-mathematical fatigue T1083, Preparing rail guidance on first night shifts T1084

[10] Rail Accident Investigation Branch. [online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/rail-accident-investigation-branch . Accessed 23 October 2017.

[11] Elisabeth L, Gregory K et al. Crew factors in flight operations XI: a survey of fatigue factors in regional airline operations. NASA/TM 1999 208799

[12] Craig A. Jackson, Laurie Earl; Prevalence of fatigue among commercial pilots, Occupational Medicine, Volume 56, Issue 4, 1 June 2006, Pages 263–268, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kql021

[13] Smith MR, Eastman CI (2012), “Shift work: health, performance and safety problems, Traditional countermeasures and innovation management strategies to reduce circadian Misalignment”. National Science Sleep 2012; 4:111-32

[14] Interdynamics (2016) “Focus on fatrigue, Issue 39: Napping on the night shift. [Online], available at https://www.interdynamics.com/2016/01/10/focus-fatigue-issue-39/ . Accessed on 31 October 2017

[15] Hult International Business School: Culpin V, Russell A (June 2016) “The Wake-up Call, The importance on sleep in organization life. [Online ], available at http://www.hult.edu/news/how-sleep-deprivation-affects-work-and-performance/#. Accessed on 23 October 2017.

[16] UK Government guidance, Driver & Vehicle Licensing Agency (March 2016): “Assessing fitness to drive: a guide for medical professionals”. [Online], available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/assessingfitness-to-drive-a-guide-for-medical professionals. Accessed 30 August 2017

[17] Simplyhealth, (april 2016), “UK workers demand a proper lunch break. [Online],available at: http://newsroom.simplyhealth.co.uk/uk-workers-demand-a-proper-lunch-break/. Accessed 30 August 2017.

[18] The British Psychological Society (January 2017), “UK employers could do more to encourage staff to switch off at home”. [Online], available at: https://beta.bps.org.uk/news and-policy/uk-employers-could-do-more-encourage-staff-switch-home. Accessed 30 August 2017.

[19] Fatigue Science predictive technology. [Online] , available at:

https://www.fatiguescience.com/applications/industry-transportation-fatigue-risk/. Accessed on 23 October 2017.[20] Health and Safety Executive (2006), “The development of a fatigue/risk index for shiftworkers” [Online], available at: http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrhtm/rr446.htm. Accessed 30 August 2017.

Additional Resources

Dongping F, Zhongming J, et al. “An experimental method to study the effect of fatigue on construction workers’ safety performance”. Safety Science Volume 73, March 2015 80-91

Zhang M, Murphy LA, Fang D, Caban-Martinez AJ. Influence of fatigue on construction workers’ physical and cognitive function. Occupational Medicine 2015 DOI: 10.1093/occmed/kqu215

Keckland G. & Axelsson J, (November 2016), “Health consequences of shiftwork and insufficient sleep”. The bmJ, [Online], available at: http://www.bmj.com/content/355/bmj.i5210

Vedaa O, Harris A, Bjorvatn B, et al. “Systematic review of the relationship between quick returns in rotating shift work and health-related outcomes”, Ergonomics, DOI: 10.1080/00140139.2015.1052020.

-

Authors

Christina Butterworth RN, SCPHN, Hon.FFOM - Crossrail Ltd

Christina is the Crossrail Occupational Health and Wellbeing Specialist, and is ultimately responsible for leading the organisation’s effort to prevent work related ill health and promote good health and wellbeing at work.

Working as part of the Health and Safety Improvement team, she provides high level support and advice on evidence based practice and quality standards. Managing the Crossrail health and wellbeing programme and collaborating with our Principal Contractors on targeted intervention and robust process management.

Christina has had a varied career in occupational health working for a number of large national and international organisations and works tirelessly to continuously improve occupational health and wellbeing. Working with like-minded individuals to provide optimal health for our staff and leadership commitment at all levels.

Christina joined Crossrail in 2014 and works with stakeholders in the Construction and Rail industries to set standards of good practice. -

Acknowledgements

TfL, For conducting the initial fatigue research

BBMV, For conducting follow-up research and sharing results