Implementing Contractual Skills and Employment Targets

Document

type: Technical Paper

Author:

Andrew Eldred MA, MSc, Anne-Sophie Blin MSc

Publication

Date: 17/08/2018

-

Abstract

This learning legacy paper first describes the background context for Crossrail’s imposition of contractually binding skills and employment targets, then outlines the key features of each of these targets and the planning, reporting and performance management processes developed to support them.

An explanation of the main implementation issues experienced on the project, and how Crossrail and its contractors sought to address them, is followed by key lessons learned and recommendations.

This paper should be of interest both to clients on future projects looking to develop their own regime of skills and employment targets and to contractors wishing to improve their delivery of such targets.

-

Read the full document

1 CONTEXT

1.1 Addressing skills and employment challenges on major infrastructure projects

In its Skills and Employment Strategy, published in 2010, Crossrail identified a range of strategic skills and employment challenges which it undertook to address over the lifetime of the project. These challenges included:

- Labour forecasts predicting a need for approximately 55,000 workers over the duration of the project, with a peak workforce requirement of 10,000;

- Labour market data indicating significant skills gaps in some construction and engineering occupations, most notably tunnelling and underground construction;

- Various reports suggesting that the UK infrastructure sector was struggling with the issues of an ageing workforce and its apparent unattractiveness to young people;

- Surveys confirming that several localities abutting the Crossrail route were characterised by comparatively high levels of unemployment and low levels of educational attainment and marketable vocational skills.

In seeking to address these challenges, Crossrail aligned itself with an emerging trend on major infrastructure investments. This trend has been to seek to exploit the potentially substantial job and training opportunities created by such investments both to counteract serious dysfunctions within the construction labour model and to help alleviate wider problems of economic, social and educational disadvantage. Earlier manifestations of the trend in the UK have included local authority employment and training conditions attached to planning consents under section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990.

1.2 Olympic Park

A closer precedent to Crossrail in terms of timing and scale was provided by the London 2012 Olympic Park. Significantly, however, whilst the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) imposed public commitments around jobs for local people and a minimum number of apprenticeships on itself, it mostly relied on encouragement and persuasion, rather than contractually binding targets, to secure contractors’ cooperation in delivering these commitments. With hindsight, the ODA accepted that this absence of targets had made it more difficult to achieve its skills and employment objectives than might have been the case otherwise, and recommended in its legacy report on apprenticeships that in future ‘legally binding clauses need to be included in contracts or planning arrangements’.[1]

1.3 TfL and SLNT targets

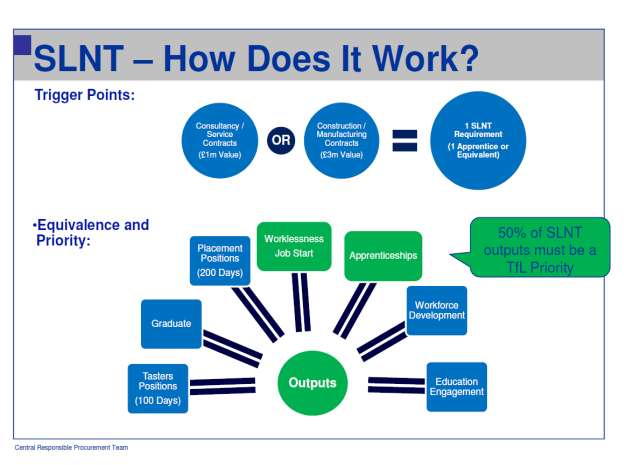

As a wholly owned subsidiary of Transport for London [TfL], Crossrail was fortunate to be able to draw on TfL’s ‘Strategic Labour Needs and Training’ [SLNT] system as a model for contractually binding skills and employment targets. The defining feature of the SLNT system is that it commits each supplier to deliver a minimum number of skills and employment ‘outputs’. This number is calculated using a formula based on the tendered value of the contract in question. SLNT outputs are divided between so-called ‘priority’ areas (i.e., unemployed job starts and apprenticeships) and other, lower priority activities.[2] Figure 1 below offers an illustration of how the system is intended to work.

Figure 1 – TfL Strategic Labour Needs and Training system

2 CONTRACTOR SKILLS AND EMPLOYMENT TARGETS

2.1 Contractual SLNT targets

In its Skills and Employment Strategy, Crossrail formally confirmed its intention to adopt the SLNT system on the project. This statement of intent was then enacted by provisions in Part 15 of Crossrail’s Works Information, entitled ‘Responsible Procurement’ [RP]. These included:

- A method for calculating the minimum total SLNT target for each contract based on the formula of one SLNT output for every £3m of tendered value;

- A requirement on Tier 1 contractors to allocate at least half of all SLNT outputs generated using this formula between the priority areas of unemployed job starts and/or new apprenticeships;

- A finite list of other SLNT activities. As with TfL, these non-priority areas included graduate training, workforce skills, work placements and work experience;

- A separate contractual requirement on Tier 1 contractors to ensure that all job vacancies, including subcontractor vacancies, were advertised first through the Crossrail Jobs Brokerage, operated in partnership with Jobcentre Plus.

2.2 Contractual SLNT definitions

To make its expectations as clear as possible, Crossrail also included detailed qualifying conditions in its contracts for each type of SLNT activity: reproduced in Table 1 below. By reducing the scope for work-arounds and ‘box-ticking’, these conditions also aimed to protect the integrity of the targets themselves.

Table 1 – Crossrail Contractual SLNT Definitions

SLNT category ‘Priority’ SLNT? Contractual definition

Output value Job start

Yes

An individual employed for 16 hours a week or more beginning a position of employment with a minimum duration of 26 weeks to include one / both of the following:

· A sustainable job start for an individual from the local community (see Note) that is workless/unemployed/out of education or training;

· A sustainable job start for an individual who has been long-term workless/ unemployed/ out of education or training for at least six months.

(Note: A ‘local’ person for these purposes was defined as someone resident either in one of the Greater London boroughs or one mile either side of the Crossrail route outside London.)

1 output per job start

Apprenticeship (new) Yes

An individual employed for a minimum of 16 hours a week who is undertaking a sector skills council / standard setting body recognised structured programme of training leading to the completion of a full apprenticeship.

1 output per year of the apprenticeship Apprenticeship (existing) No Half an output per year of the apprenticeship Graduate training No An individual employed for 16 hours a week or more who has recently completed their undergraduate degree and is beginning an employment position on a formal graduate trainee scheme with a minimum duration of 6 months. 1 output per graduate trainee Workforce skills No Workforce training or development activity for full time employed individuals of an accredited course of learning and development and/or nationally recognised qualification or industry recognised programme measured in complete days. 1 output per 100 days Work placement No A position intended to enable an individual to learn, develop or enhance their knowledge and skills in relation to the employment market that lasts between 11 days and 100 days and which includes elements of job coaching and support. 1 output per 100 days Work experience No A position intended to introduce an individual to a specific industry, occupation or position and may have a duration between 1 day and 10 days of structured activity 1 output per 100 days 2.3 Contractual planning and reporting procedures

In addition to the above substantive terms, Part 15 of the Crossrail Works Information imposed significant procedural requirements on each Tier 1 contractor, covering the planning and reporting of Tier 1 and supply chain delivery of SLNT outputs, as set out below.

2.3.1 Responsible Procurement Plans

Each organisation bidding for a significant Crossrail Tier 1 contract was required to submit a draft Responsible Procurement Plan at tender stage. Among other things, these Plans were intended to outline how the bidding organisation proposed to meet its SLNT targets, including the allocation of outputs between different SLNT categories and the timeframes within which targets would be delivered. Crossrail reviewed each bidder’s draft Plan as part of the tender evaluation process. Once the decision to award the contract was made, SLNT targets were formally embedded in the contract (calculated in accordance with the one output per £3 million formula) and the successful bidder allowed four weeks in which to resubmit its Plan to Crossrail for final approval.

2.3.2 Quarterly Responsible Procurement reports

Each Tier 1 contractor was contractually required to provide updates on its progress in meeting SLNT targets as part of an RP report submitted to Crossrail once a quarter. The information supplied in this way identified how many new job starts, apprenticeships, graduate trainees, etc. had started on a particular contract over the preceding quarter. Contractors were also expected to provide additional supporting information about each SLNT beneficiary for verification and stakeholder reporting purposes (e.g., name of employer, job title or apprentice framework, previous employed/ unemployed status, date of birth, gender, ethnicity, any disability, home postcode, etc.).

2.4 Non-contractual performance assurance process

Every six months, between January 2013 and January 2016 inclusive, Crossrail carried out formal (albeit non-contractual) assessments of contracts’ performance, including each Tier 1 contractor’s progress in meeting its SLNT targets. In line with broader performance assurance principles, Crossrail ranked Tier 1 contractors against pre-determined performance criteria. For SLNT targets, the different performance levels were (by January 2016) defined as follows:

- Basic compliance: the Tier 1 contractor could demonstrate that it was making progress towards the delivery of its contractual SLNT targets and had processes in place to cascade these targets down its supply chain;

- Value-added performance: in addition to the Basic Compliance criteria above, the Tier 1 contractor could demonstrate a stretch target for apprenticeships (i.e., above the contractual minimum), a detailed plan for delivering that target, and active supply chain engagement with the Crossrail Jobs Brokerage;

- World-class performance: in addition to the Basic Compliance and Value-Added criteria, the Tier 1 contractor could demonstrate a tailored approach to supply chain apprenticeship targets (i.e., not simply replicating the one output per £3 million formula), and active support for Brokerage-led employability initiatives.

Further details about the relevant performance assurance process are included in a separate learning legacy paper.

3 IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES

As with anything comparatively new and untested, the implementation phase ultimately highlighted some areas of weakness and therefore opportunities for improvement.

3.1 Weaknesses in contractors’ delivery plans and processes

Despite the formal requirements around submission, client review and approval of RP Plans [see 2.3.1, above], in practice most such Plans started out quite light on the processes and resources each contractor intended to utilise in order to achieve its SLNT targets. In many cases these Plans were little more than a copy of the relevant contract terms. However, because at the time the SLNT regime was still very new, and without experience of operating a similar regime themselves, the Crossrail staff charged with scrutinising Plans were at this stage understandably reluctant to put forward suggestions of their own about what good practice might look like. Instead, Crossrail initially focussed its attention on simple output measures of performance – principally, numerical progress in delivering the targets themselves – rather than on how Tier 1 contractors were going about achieving them.

Once the project got fully under way, and after successive PAF assessment rounds, Crossrail started to identify several knock-on effects from these weaknesses in contractors’ original RP Plans. First, practices varied markedly from contract to contract, with dramatic gaps between the most and least effective, producing in turn significant differences in both the quantity and – even more strikingly –quality of SLNT outcomes. Secondly, on many contracts actual management processes differed wildly from those set out in their Plans, complicating unnecessarily attempts to analyse the factors underlying good and bad performance. Finally, ambiguities about the roles and responsibilities of different Tier 1 contractor staff in supporting the delivery of SLNT targets tended to place too much onus on the personal effectiveness of the individual fulfilling the role of RP Representative on that contract, and to blur accountability in the event of under-performance or poor practice.

3.2 Complexities of SLNT reporting

The allocation of Tier 1 contractors’ obligations between as many as seven different SLNT categories, together with the volume of supporting information required for each reported SLNT output, resulted in large and complex data-sets which were not always straightforward for Crossrail to collate, analyse or verify. These issues were compounded by inconsistencies in the quality of contractors’ reports (viz. incorrect data, missing fields, etc.). Consistently keeping track of retrospective amendments to historic data proved especially tricky: for example, where a Tier 1 contractor reported new job starts and/or apprentices in one quarter but then had to discount some of these afterwards because individuals had, for one reason or another, left the contract before reaching the contractual threshold period of, respectively, 26 and 16 weeks. The Excel software also proved temperamental, struggling to cope with the volumes of data and complex links between data.

For their part, some Tier 1 contractors criticised Crossrail’s reporting requirements as excessive. Separate external stakeholder management considerations meant that, in addition to SLNT outputs, Crossrail required contractors to report on every local person securing a new job on the project, even where that person had not been previously unemployed and therefore did not qualify as a ‘job start’ within the meaning of the contract. Over the lifetime of the project this effectively increased the volume of jobs-related data that needed to be reported and verified by some 400%. Further non-SLNT reporting obligations added to the complexity, resulting in a quarterly social sustainability reporting template which until 2014 consisted of no fewer than thirteen separate Excel spreadsheets. Increasingly, Tier 1 contractors and Crossrail itself questioned the utility and proportionality of such levels of demand for data.

3.3 Apprenticeship target

Once most large Tier 1 contracts had been let, Crossrail assessed that its cumulative total of contractually-binding apprenticeship output commitments secured from Tier 1 contractors (443) was unlikely to be enough on its own to deliver the publicly declared target of 400 individual apprentices. This, of course, was because the duration of many advanced and higher-level construction and engineering apprenticeships (typically anything between two and four years) meant that one individual based on the project for the whole, or even part, of their apprenticeship could easily account for multiple SLNT outputs under the terms of the contract. Despite its implementation of SLNT, therefore, Crossrail ultimately found itself in a similar situation to the ODA in needing to persuade Tier 1 contractors and their supply chains to recruit significantly more apprentices than their contracts obliged them to do. As things turned out, the 400 target was reached as early as January 2015; however, this fact should not disguise the hard work and commitment demonstrated by both Crossrail and contractors to move beyond mere contractual compliance and towards maximising apprenticeship opportunities as and when these arose.

Figure 2 – Crossrail reaches target of 400 apprentices in January 2015

3.4 SLNT workforce skills category

The value of Tier 1 contractors’ reports on the SLNT ‘workforce skills’ category, unfortunately, proved particularly open to question. Although Crossrail’s contractual definition (see Figure 1 above) emphasised that training and development needed to be ‘accredited’ or ‘recognised’ to qualify, this definition proved insufficiently clear in practice. Tier 1 contractors tended to interpret most, if not all, of their existing programmes as qualifying, resulting in high volumes of reported workforce skills outputs every quarter. Given the sheer amount of this data, the ambiguity of the contract, and other demands on their time, Crossrail staff struggled to mount a sustained line-by-line challenge to such claims. Accordingly, relatively quickly and without much if any additional effort, most Tier 1 contractors were deemed to have met their contractual workforce skills target.

3.5 Labour versus capital intensive contracts

Some Tier 1 contractors felt that the metric of one SLNT output for every £3 million of tendered value was unfair to them because of the capital-intensive nature of their contracts. In practice, this presented a significant concern only for a small number of contracts where a high proportion of the contract spend was on equipment, to be installed on-site by a small workforce, with relatively few opportunities for SLNT outputs. For the majority of contracts, however, the targets were not especially onerous and contractors generally managed to meet or exceed them.

3.6 Supply chain participation

Securing greater lower-tier participation in the delivery of skills and employment outcomes proved a bigger challenge. Whilst Crossrail’s Works Information did include a requirement on Tier 1 contractors to cascade SLNT requirements to their subcontractors and suppliers in a ‘relevant and proportionate’ way, it did not specify how specific targets should be calculated or mandated in sub-contracts. Once Crossrail started to investigate individual Tier 1 contractors’ engagement with their supply chains, it quickly became apparent that very few were actively driving involvement in the delivery of SLNT outputs. In practice, in the early days of the project, most skills and employment outcomes (with the sole exception of job starts) were delivered by the Tier 1 contractors directly, usually through existing corporate schemes.

Those Tier 1 contractors who did have some engagement with their supply chain tended not to tailor their requirements to the nature of each subcontract package and uniformly cascaded the SLNT requirements using the one per £3 million metric. In Crossrail’s view, this undifferentiated approach fell short of the contractual requirement for a ‘relevant and proportionate’ approach. It also risked missing out on opportunities on labour-intensive subcontracts (e.g., with labour-only suppliers) to demand more than the standard one per £3 million metric.

3.7 Support for Crossrail Jobs Brokerage initiatives

Although reports confirmed significant numbers of local people obtaining employment during the early years of the project, not all Tier 1 contractors proved willing or able to fully comply with the contractual obligation to post all vacancies with the Crossrail Job Brokerage. This widespread failing meant that opportunities for the long-term unemployed and others from disadvantaged or under-represented groups risked falling short of expectations.

In part, this problem stemmed from weaknesses in the systems and processes adopted by Tier 1 contractors at contract level. Given that most vacancies tended to originate with subcontractors, the widespread lack of supply chain engagement already referred to [at 3.6] effectively blocked the flow of relevant information up to the Brokerage.

At the same time, contractors complained that candidates referred to the Brokerage via local job centres and employability schemes fell short of basic pre-employment requirements and in some cases displayed little genuine interest in construction careers. In their turn, Brokerage staff felt that matters were unlikely to improve until both local referral agencies and contractors received more hands-on assistance in supporting local job applicants than the Brokerage up to that point was empowered to provide.

3.8 Responses

In 2014, following consultation with its Tier 1 contractors, Crossrail implemented a series of changes to the skills and employment regime on the project, including several designed to address the implementation issues described above. In particular:

- Using amendments to the Social Sustainability PAF, Crossrail started to focus more attention on ‘input’ measures of Tier 1 contractors’ performance, including the systems, policies, procedures and resources devoted to delivering SLNT targets. This rebalancing of the PAF prompted most contractors to upgrade and update their RP Plans, assisted by Crossrail staff and using good practice examples from elsewhere on the project.

- The quarterly reporting template was substantially redesigned, including cutting down the number of spreadsheets from 13 to four.

- Crossrail began to place a much stronger emphasis on supply chain involvement in delivery of SLNT outputs. Amendments to the Social Sustainability PAF gave due weight to the Works Information provisions concerning supply chain engagement, treating the absence of such engagement as a breach by the Tier 1 contractor of its minimum contractual obligations. New Value Added and World Class criteria (as described previously at 2.4) encouraged Tier 1 contractors to go beyond minimum compliance by adopting and sharing good practice.

- Wide-ranging changes were made to the Jobs Brokerage, including:

- Establishing closer working relationships with local referral agencies, involving workshops to help employment advisers better appreciate construction employers’ expectations and proactive steps to improve local candidates’ understanding and credentials ahead of applying for jobs on the project;

- Expanding the Brokerage’s role to include, where agreed with a Tier 1 and/or supply chain contractor, sourcing of suitable local candidates for work placements and/or apprenticeships, as well as jobs starts.

- New Brokerage initiatives directly targeting disadvantaged and under-represented groups, including a partnership with Women into Construction CIC, sponsorship of the Buildforce pilot project (armed services leavers and veterans), and – in collaboration with the Department for Work and Pensions and some leading labour-only subcontractors – job-guaranteed training schemes for the long-term unemployed.

- Supportive changes to the Social Sustainability PAF, such as new performance criteria recognising Tier 1 contractors who participated in Brokerage initiatives and/or adopted measures of their own to target skills and employment opportunities towards disadvantaged or historically under-represented groups.

As well as these specific measures, Crossrail also sought to promote good practice more broadly by establishing a quarterly Social Sustainability Working Group for contractor representatives and recognising individual Tier 1 contractors and subcontractors in its annual Apprentice and Social Sustainability Awards. Examples of the latter included awards for supply chain engagement and involvement with Brokerage initiatives.

Figure 3 – Crossrail Awards

4 RESULTS

Table 2 below reproduces the SLNT data collected by Crossrail (excluding workforce skills) up to the end of comprehensive data reporting in April 2016. Whilst the number of SLNT outputs achieved has inevitably risen since that date (e.g., at the time of writing (April 2018), apprenticeships on the project’s Central Section had exceeded 700), these increases have not affected the broad analysis set out below, or the lessons learned and recommendations developed in the next section.

Table 2 measures SLNT delivery both in terms of Crossrail’s contractual output requirements and the number of real-life individuals who have benefited. It also records the ratio of SLNT outputs under each SLNT category which Tier 1 contractors have delivered themselves, and the proportion delivered by their on-site supply chains (i.e., trade subcontractors and labour suppliers). One immediately noticeable difference in this regard is that between job starts – predominantly provided through the supply chain – and other SLNT categories – predominantly delivered directly by Tier 1 contractors themselves.

Table 2 – Total SLNT delivery on Crossrail 2011 – 16

SLNT category Total no. contractually binding SLNT commitments Total SLNT delivery (as at April 2016) Output delivery % delivery of SLNT commitments Ratio of Tier 1 direct vs. supply chain delivery No. individuals benefiting Job starts 474

≤ 771 ≤ 163% 19: 81 ≤ 771 Apprenticeships 443 ≥ 573** ≥ 130% 75: 25 573 Graduate training 166

463 279% 72: 28 463 Work placements 49.8

(=4980 days)

14918 days 300% 91: 9 443 Work experience 37

(=3700 days)

3590 days 97% 99: 1 844 4.1 Overall delivery of SLNT outputs

Column 3 of Table 2 confirms that the cumulative number of SLNT outputs delivered by April 2016 had exceeded Tier 1 contractors’ global SLNT commitments in all but one area (i.e., work experience, the target for which has since been met). For the most part, individual Tier 1 contractors also met or exceeded their contractual SLNT targets, although some found this easier to achieve than others. With hindsight, therefore, it could be argued that Crossrail’s one output per £3 million metric should have been made more demanding (this question is considered further under lessons learned and recommendations, at 5.1 below).

The present report will now turn from SLNT results in general to comments on particular SLNT categories, beginning with job starts.

4.2 Job starts

The 771 job starts in Figure 3 represent the total number of unemployed local people reported by Tier 1 contractors as having begun a new job on the project by April 2016 (i.e., the first category of ‘job start’ defined in the contract (see Figure 1 above)). Figure 3 expresses this as a maximum number since Crossrail only ever managed to obtain partial assurance from Tier 1 contractors that the contractual requirement of not less than 26 weeks’ sustained employment was also being met: something made more difficult to establish by the fact that a large majority of job starts were provided by supply chain employers rather than by Tier 1 contractors themselves.

By April 2016, Tier 1 contractors were also reporting over 200 unemployed non-local people as having begun a new job on the project. None of these has been included in Figure 3 above, however, because in practice Crossrail was unable systematically to verify data from contractors on the duration of new starters’ previous period of unemployment: a necessary precondition to qualify under the contract’s second (long-term unemployed) definition of a job start.

4.3 Apprentices

Whilst Crossrail’s contracts expressed Tier 1 contractors’ apprenticeship obligations in terms of outputs (i.e., a minimum of 16 weeks on the project as an apprentice in any one year), in practice apprentices were generally reported and recorded as ‘heads’ (i.e., every individual was counted once, even if their time as an apprentice on Crossrail continued for several years). For this reason, Figure 3 expresses the April 2016 total of 573 apprentices as a minimum number, with the total number of outputs, as defined in the contract, bound to be significantly higher.

Various factors led to this apparent, and sometimes confusing, mismatch between contractual requirements and reporting practice. These included the somewhat esoteric nature of the ‘output’ concept itself: especially evident when the contract required contractors and Crossrail to differentiate between new and existing apprenticeships, the latter being deemed to have half the output value of the former. More important, however, was the fact that Crossrail had previously expressed the target in its own Skills and Employment Strategy in terms of heads. Consequently, and unsurprisingly, senior managers were primarily interested in understanding how well Tier 1 contractors were progressing towards this target. Accordingly, even though Crossrail staff continued informally to check each Tier 1 contractor’s delivery of apprenticeship outputs, and half-outputs, as part of the PAF performance assurance process, they adjusted their formal reporting metrics to mirror the 2010 Strategy target, rather than the contractual position.

4.4 Jobs Brokerage

The Jobs Brokerage’s efforts to improve the work readiness of local applicants largely silenced contractors’ earlier criticisms, and proved especially helpful in strengthening relationships with a handful of Tier 1 and Tier 2 employers who then agreed to support pilot job-guaranteed training schemes. These involved local long-term unemployed jobseekers who had passed an initial interview with an employer, and then undertook training in entry-level occupations such as traffic marshalling on the understanding that there would be a job for them at the end of it.

Despite the additional challenges of the second phase of the project, when Tier 1 contractors’ supply chains are more complex and new job opportunities more fragmented, these initiatives helped the Brokerage maintain a success rate of around 65% for entry-level jobs, benefiting Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) candidates especially. However, with limited time and resources and an absence of specific contractual levers, there was little opportunity to see if such activities could be scaled up, and so their impact on the ethnic diversity figures for job starts as a whole was quite marginal. Similarly, whilst the partnership with Women into Construction reinvigorated Crossrail’s existing communications campaign promoting greater gender diversity, and in just over two years generated 31 work placements and 30 job starts for women (benefiting 44 individuals in total), these outcomes were not enough on their own significantly to improve overall gender diversity figures on the project.

Crossrail’s attempts to encourage contractors to diversify recruitment – for example, by specifically targeting employment and skills opportunities towards historically under-represented groups – seem to have had little real impact. Anecdotally, Crossrail became aware of one Tier 1 contractor introducing a policy that equal numbers of female and male candidates should be considered in the first stage of the selection process for all new jobs. This practice was confined to one contract, however, and there was little evidence of contractors developing targeted diverse recruitment initiatives elsewhere.

5 LESSONS LEARNED AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Whilst the numbers do not lie, and a significant degree of success was achieved on the Crossrail project thanks to those responsible for designing and implementing the SLNT regime, the present report is principally written with an eye to the future and pointing out ways in which the Crossrail legacy can be built upon and improved.

This approach is continued in the next section, which attempts to draw together some of the main threads into a series of key lessons learned and recommendations for clients and contractors involved on major infrastructure investments in future. Such an exercise will hopefully prove even more timely given the much more sympathetic environment towards contractually binding skills and employment targets now existing in 2018, in comparison with the situation when the Crossrail project first got under way, back in 2010. To some degree the successes of the SLNT system adopted on the project has no doubt contributed to this improved environment. Other factors have also played their part, however, including (for example):

- Changes to EU and UK public procurement law, embodied in the UK by the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 and the Public Contracts Regulations 2015;

- Growing opinion that existing construction business and labour models in the UK require radical new prescriptions, such as those outlined by Mark Farmer in his independent report entitled ‘Modernise or Die’; [3]

- Growing Government and industry support for reviving take-up of apprenticeships, exemplified by the national target for a total of 3 million new apprentice starts, and several sector-specific initiatives, such as Sir Terry Morgan’s Transport Infrastructure Skills Strategy; [4]

- Further innovations – building on the Olympics and Crossrail – from new and upcoming infrastructure projects, such as Tideway, [5] Hinkley Point C, High Speed 2 and the Heathrow Third Runway.

As part of this now fortunately virtuous circle, it is hoped that the following insights drawn from over seven years of experiences on Crossrail will assist future clients and contractors to develop their own, more effective approaches to maximising the skills and employment opportunities created by major infrastructure projects.

5.1 Calculating numerical targets

Perhaps appropriately for a report with the word ‘targets’ in its title, the first lesson learned and recommendation focuses on the benefits of targets themselves, how they should be calculated and the particular implications of targets linked, as they were on Crossrail, to contract value.

5.1.1 Targets are important

For Crossrail, the benefits of contractually-binding numerical targets were two-fold. First, targets set a minimum expectation of what Tier 1 contractors and their supply chains should deliver, thereby creating an explicit, objective measure of what level of performance was necessary to constitute success. Secondly, by giving skills and employment initiatives contractual relevance, SLNT targets helped to raise the profile of these initiatives within both the client and contractor organisations, imbued Crossrail’s monitoring and performance assurance processes with greater significance, and offered a springboard for some contractors to adopt additional measures exceeding minimum compliance.

5.1.2 Targets based on workforce ratios might not always be practicable

In terms of the method it used to calculate numerical targets, Crossrail was and remains satisfied that, at least on major capital projects like this one, an approach based on contract value is preferable to one based on the number of individual beneficiaries, such as apprentices, as ratios of the overall workforce. Whilst headcount forecasts might provide a useful guide in some circumstances (for example, where there a reasonably stable direct workforce and only limited use of subcontractors), Crossrail has found that, in practice, Tier1 contractors often struggle to provide reliable long or even medium-term forecasts of workforce numbers.

Various factors account for these difficulties. These include Tier 1 contractors’ generally heavy reliance on subcontractors rather than their own employees, especially in the later building and fit-out stages of the project. More often than not, main contractors in the UK attempt to transfer risk to these subcontractors by awarding packages of work on a fixed-price basis, rendering information about likely workforce numbers commercially irrelevant and therefore generally invisible. Even assuming that commercial obstacles of this kind can be overcome, daily headcount fluctuations at site level and unplanned changes to the programme of work arguably make it impossible to choose, at tender stage, a particular point in time as the baseline for calculating targets derived from overall workforce numbers.

5.1.3 Take account of other relevant considerations when designing targets

By comparison with workforce numbers, therefore, Crossrail remains convinced that contract value provides a more stable and consistent basis for calculating each Tier 1 contractor’s contractual SLNT obligations in a ‘fair’ way. The approach is not without its complexities and pitfalls, however, and future clients should consider these issues up front when drafting their contracts. Potential issues include:

- Whether to express targets in the form of ‘outputs’ or individual beneficiaries. As has been seen (at Figure 1 above), the SLNT system on Crossrail incorporated some targets expressed as numbers of individuals benefiting (e.g., job starts and graduates), and others defined in more abstract terms as ‘outputs’ (e.g., apprenticeships and work placements). Clients should take particular care when expressing targets in terms of numbers of individual beneficiaries, in order to avoid:

- Incentivising contractors to maximise numbers at the expense of quality (for example, by recruiting large cohorts of apprentices on low-quality or irrelevant standards of short duration);

- Damaging individuals’ longer-term development and/or employment prospects by discouraging employers from transferring them elsewhere because they might then cease to ‘count’ for target purposes.

- Setting contractual targets which are ambitious but still achievable. Given that most Tier 1 contractors managed to meet or exceed their contractual targets, there is, with hindsight, an arguable case that Crossrail could have demanded more than one SLNT output per £3 million of contract value. For example, the Transport Infrastructure Skills Strategy in 2016 adopted a more ambitious approach, committing participating client organisations to impose a contractual requirement of one entire apprenticeship, regardless of duration, for every £4 to £5 million of contract value. [4]. On the other hand, care should be taken not to impose overly ambitious targets, especially where, as on Crossrail, several different skills and employment objectives are competing for attention. In the same spirit, it is worth remembering that contractual targets are designed to establish a floor for achievement, but not necessarily a ceiling, leaving ample scope for voluntary effort, collaboration and innovation to deliver significantly more than the minimum in the end.

- Adjusting targets to reflect changes in contract value. This issue can arise, for example, where work scope is transferred from one contractor to another, or additional work is identified which was not foreseen when a contract was first awarded. In such circumstances, contractual provisions need to set out a clear and simple process for varying a contractor’s targets to reflect any significant increase, or decrease, in contract value.

- Confirming stance towards off-site skills and employment outcomes. Generally, Crossrail’s SLNT provisions required contractors and their supply chains to deliver skills and employment outcomes within a contractually defined ‘working area’: typically, the construction site and site office. For this reason, most off-site initiatives – for example, apprenticeships created during manufacture of the tunnel-boring machines – did not count towards the achievement of contractors’ targets. This restriction proved controversial with a few contractors, especially on smaller, more capital-intensive contracts. It also meant that potentially significant social benefits connected with the project went unmeasured and unreported. Both the UK Government and industry leadership bodies have publicly committed to increase the use of pre-manufactured components on public infrastructure and other construction projects. For this reason, as well as the others already cited, future clients will probably need to find a way to include, and even to encourage, off-site skills and employment outcomes as part of their contractual targets. This exercise will involve navigating around several potential pitfalls, including:

- Defining whether an off-site job start, apprenticeship, graduate place, etc. must be wholly connected with the project in question in order to count, or if the beneficiary can spend some time on other work (and, if so, how much);

- Confirming if all targets must be delivered within the UK, or if jobs, apprenticeships, graduate places, etc. generated by contracts and subcontracts awarded overseas may also count;

- Ensuring accurate reporting of off-site outcomes. Varying degrees of subcontracting and/or geographical distance can make these much more difficult to verify than equivalent outcomes on site.

- Making some allowance for differences between labour and capital-intensive contracts. Whilst an overly flexible system will almost certainly prove unworkable, it should be possible to display some sensitivity to limitations on the practicability of delivering a sizeable number of new jobs, apprenticeships, etc. on contracts which principally involve supply of high-value capital equipment and only a small on-site labour requirement. In particular, early engagement during procurement and/or immediately after award should make it easier for a client and contractor to negotiate suitable adjustments to the standard targets regime – for example, by placing a greater emphasis on graduate and/or off-site opportunities, possibly coupled with an enhanced commitment to invest in UK-based design and manufacturing.

Recommendation 1:

In line with Mark Farmer’s ‘Modernise or Die’ report and Sir Terry Morgan’s Transport Infrastructure Skills Strategy, more clients from both the public and private sector should start imposing contractually binding numerical skills and employment targets on their construction supply chains. Whilst targets based on workforce ratios might operate well in more stable or predictable environments, on most large construction projects contract value is probably an easier and more consistent starting point for calculating contractors’ obligations. In designing a targets regime based on contract value, however, clients should also consider:

- How numerical targets ought to be expressed (i.e., in terms of individual beneficiaries or more abstract ‘outputs’);

- How to ensure that targets are sufficiently ambitious, yet still achievable;

- How to ensure that any public commitments are contractually deliverable;

- How to respond to subsequent changes in contract value;

- How to accommodate off-site initiatives;

- How to deal fairly between labour-intensive and capital-intensive contracts.

5.2 Prioritising and defining targets with reference to broader social objectives

Having accepted the potentially valuable role of contractually binding skills and employment targets, it is at least as important for clients to take care to select the right targets and define those targets properly. With multiple, and sometimes conflicting, stakeholder demands, clients are at obvious risk of becoming overwhelmed, and imposing on contractors an incoherent, and ultimately undeliverable, wish list.

The solution, of course, is for clients to keep things as simple as possible, with a finite number of priority areas linked to key skills and employment objectives. In doing so, each client will no doubt wish to take account of a range of factors, including the concerns and aspirations of its own organisation and the locality, or localities, in which a project is based, as well as wider sectoral and external stakeholder considerations.

5.2.1 Combining skills and employment and broader social objectives

As with all numerical targets, it is important to bear in mind the quality of skills and employment outcomes as well as their quantity. One way for clients to achieve this is to establish from the outset a clear vision of the broader social objectives which achievement of these targets is intended to support. Keeping this bigger picture in mind should bring several benefits, including:

- Demonstrating a closer link to specific, measurable social benefits should make it easier to mobilise internal and contractor support for skills and employment targets;

- Sending a clear message to contractors that contractual skills and employment targets are more than just a ‘numbers game’, and demand proper planning, adequate resources and effective processes to deliver;

- Increasing the chances that future projects will be able to scale up programmes targeting particular sources of disadvantage, in a way that Crossrail struggled to achieve in its later initiatives with, for example, Women into Construction and job-guaranteed training schemes.

Examples of how different SLNT-style categories might be tied more explicitly to delivery of broader social benefits are included below.

5.2.2 Job starts: differentiating between political/ stakeholder and genuine social objectives

Large construction projects like Crossrail tend to generate considerable media and political interest in the number or proportion of ‘local’ people working on the project. Whilst potentially useful from a community and stakeholder relations perspective, local participation measures of this sort do not represent an adequate proxy for a proper system of skills and employment targets. Local people may obtain employment for various reasons, some entirely unrelated to any intervention from the client or its contractors. For example, a local person might already be part of a contractor’s workforce or network, or someone whose existing skills and experience would probably have helped secure a job any way. Local employment targets are especially unhelpful where they fail to take account of demographic and cultural differences between communities. In London, for example, Newham possesses a much higher proportion of residents with recent construction skills and experience than the neighbouring borough of Tower Hamlets.

By focussing on unemployment, including long-term unemployment, Crossrail’s original ‘job start’ targets were correctly designed to deliver genuine, socially valuable benefits for local people and others. In practice, however, this focus became somewhat blurred by demands from other parts of the organisation for data about the number of local people working on the project, whether previously unemployed or not. First, as has been seen already [see 3.2], this increased the volume of jobs-related data submitted by contractors each quarter by something like 400%. Secondly, the resulting administrative burden from collating and verifying the additional data almost certainly helped divert attention away from the arguably more relevant task of capturing better data on recruitment of the long-term unemployed and whether ‘job starts’ were genuinely sustainable.

For present purposes, the most pertinent learning point from Crossrail’s experience is that clients should take care to maintain a clear distinction between genuine skills and employment initiatives on the one hand and externally-driven local employment targets on the other. Where (as will often be the case) meeting local needs constitutes one of the main objectives of a project’s skills and employment strategy, then any resulting targets should be designed to deliver real social benefits by addressing these needs directly: through, for example, targets focussed on employment opportunities for local young people, the long-term unemployed, and/or those from historically disadvantaged or under-represented groups.

5.2.3 Apprenticeships: maximising relevance and quality

Not all apprenticeships are equal, and by incorporating certain qualifying conditions into its contractual definition of apprenticeships (see Figure 1 above), Crossrail managed mostly to avoid the potential pitfalls associated with a multiplicity of apprenticeship schemes of possibly inconsistent utility and quality. Beyond these minimum qualifying conditions, however, Crossrail never sought to fetter contractors’ discretion over the discipline or level of the apprenticeships used to meet their targets.

Whilst there is little evidence of contractors widely abusing this freedom, Crossrail’s separate legacy report on Apprenticeships has previously recommended that in future clients should consider imposing tighter controls on contractors’ selection of apprenticeships. Such controls could take the form, for example, of a minimum proportion of apprenticeships dedicated to engineering and construction disciplines, the adoption of new technology, or especially acute areas of skills shortage. Additionally or alternatively, clients could look to restrict or exclude use of lower-level and/or less relevant apprenticeships.

The Apprenticeships legacy report provides further detail on these and other qualitative considerations when designing apprenticeship targets in future.

5.2.3.1 New versus existing apprentices

A related issue is whether and to what extent contractually-binding targets should recognise the employment of existing as well as new apprentices. On Crossrail, contractors were able to assign part of their SLNT commitment to existing apprentices, albeit at a lower output value than new apprentices. By contrast, the parties to the Transport Infrastructure Skills Strategy, for example, have stated that only newly created apprenticeships will count towards achievement of their 30,000 target.

Given the strategic objective of growing the overall amount of apprenticeship training, it is understandable that clients would wish to prioritise new over existing apprentices. On the other hand, there are strong arguments against disregarding existing apprentices altogether. For example:

- Clients may wish to give some credit to those organisations which regularly employ apprentices, in contrast to those who do so only in response to a specific client or planning requirement [see also 5.7d), below];

- Crossrail’s own experience confirms that organisations with a pre-existing corporate apprenticeship scheme are more likely to commit to apprenticeship targets (including for new apprentices) than those without a corporate scheme [see further 5.6.3]. The quality of individuals’ experience of apprenticeship is also likely to be better in the former case than the latter;

- If clients are to encourage greater subcontractor participation in apprenticeship provision, then they need to acknowledge the reality that many subcontractors’ relatively short period working on a particular site may limit their scope for contributing large numbers of new apprenticeships;

- There can be circumstances (especially during an economic downturn) when keeping existing apprentices in employment, and therefore able to complete their training, will prove at least as social valuable as creating new apprenticeships;

- Assuming that one of the ultimate goals of client-led skills and employment targets is to help the UK construction sector re-establish a capability to sustain and renew itself through effective recruitment and training, then clients will, over time, have to shift their emphasis away from sponsoring one-off, project-specific initiatives, and more towards influencing, supporting and strengthening more permanent industry-led schemes and institutions [see also 5.7e)].

5.2.4 Workforce skills: promoting genuine up-skilling

As described at 3.4 above, Crossrail’s experience with the SLNT workforce skills category proved somewhat unsatisfactory. Given the importance of upskilling and re-skilling, not least in reversing decades of under-investment, this experience should not discourage other clients from trying to do better, however. Rather, Crossrail’s difficulties in enforcing its own, insufficiently precise provisions suggest that clients should take care to ensure that any similar targets in future are drawn up in a clearer and more prescriptive manner.

Genuine up-skilling involves a substantive deepening and/or broadening of the responsibilities or tasks which an individual is competent to undertake. According to the UK’s present vocational education and training system, this process can be independently verified through acquisition of formal qualifications, classified as diplomas, certificates or awards. As with apprenticeships, therefore, it is open to clients in the future to use contractually binding skills and employment targets to help drive workforce acquisition of formal qualifications issued by an awarding body regulated by Ofqual. These might include, for example qualifications relating to particular priority areas – such as off-site construction techniques, cross-skilling or multi-skilling, team leadership and/or supervisory skills. The potential for the UK Government apprenticeship levy from April 2017 to encompass up-skilling and re-skilling of existing employees might also have a potentially beneficial impact on this area in future.

5.2.5 Work placements, work experience and graduates: focus on longer-term impact

The relative ease with which Crossrail’s Tier 1 contractors managed to exceed their commitments perhaps calls into question the purpose of imposing simple numerical targets in relation to work placements, work experience and graduates. Rather than withdrawing support for these initiatives, however, one option might be to use targets to increase their longer-term impact. Instances of this more strategic approach towards work placements on Crossrail, for example, have included:

- Some Tier 1 contractors’ use of work placements as part of apprentice recruitment and selection;

- Crossrail’s partnership with Women into Construction, enabling the latter to set up work placements for women with a range of different employers, leading to an offer of a job or apprenticeship in most cases;

- Crossrail’s support for the Buildforce initiative, which adopts a similar work placement-based model for service leavers seeking a job or apprenticeship.

Building on these examples, clients might, for instance, design targets aimed at

- Improving female, BAME and other target groups’ participation in graduate, work placement and work experience schemes;

- Maximising the proportion of work placements leading directly to an offer of a job or an apprenticeship;

- Measuring and improving the individual impact of work experience (e.g., proportion of schoolchildren indicating a stronger preference for a career in construction/ engineering after a work experience placement than before).

Recommendation 2:

When designing numerical skills and employment targets, client organisations should aim to maximise impact by:

- Keeping things as simple as possible, with a finite number of priority areas linked to key objectives;

- Explicitly combining skills and employment targets with broader social objectives, through (for example):

- Tying job targets to specific areas of social need (e.g., long-term unemployed, young people, ethnic minorities, etc.);

- Influencing the relevance and quality of apprenticeships, including recognition of both new and existing apprenticeships;

- Promoting genuine up-skilling through acquisition of formal diplomas, certificates or awards issued by an Ofqual-regulated awarding organisation;

- Placing more emphasis on the longer-term impact of work placements, work experience and graduate schemes.

5.3 Putting appropriate staff and organisational structures in place

As well as targets themselves, a key success factor for the skills and employment regime on Crossrail has been the people directly responsible for delivering these targets, both on the client and contractor sides. Important lessons have been learned over the course of the project about the skill-set and management structures required for these people to operate at their maximum potential.

5.3.1 Client staffing and organisation

Within Crossrail, both the specialist staff and how they were organised altered quite significantly over the course of the project. Initially, oversight of Tier 1 contractors’ delivery of their contractual RP obligations – including SLNT targets – was allocated to a small team within Crossrail’s Procurement Directorate. At the same time, a Skills and Employment team, based in the Talent and Resources Directorate, took responsibility for certain Crossrail-led initiatives, such as the Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy [TUCA], the Jobs Brokerage partnership with Job Centre Plus, and the Young Crossrail schools engagement programme.

Coordination between the two Crossrail teams took time to become fully effective. At the outset organisational boundaries were arguably compounded by occupational ones, with procurement specialists possessing only limited understanding of the subject matter of the SLNT targets which they were charged with monitoring and enforcing, and employment, training and HR specialists in the Talent and Resources Directorate generally unfamiliar with the challenges of working through contract supply chains. Some Tier 1 contractors also raised complaints about overlapping work streams and duplication of effort. There were also growing concerns that potential synergies – for example, between SLNT targets on the one hand, and TUCA and the Jobs Brokerage on the other – were not being exploited adequately.

A succession of steps mid-way through the project helped to address many of these issues, thereby ensuring a more coherent and joined-up approach from Crossrail for the remaining period. These included:

- Transferring relevant procurement specialists across to the Talent and Resources Directorate, where they were eventually merged with the Jobs Brokerage into a single, extended Social Sustainability team;

- Carrying out a review of the range of initiatives already being undertaken as part of Crossrail’s Skills and Employment Strategy, and potential synergies and gaps;

- Redrafting Crossrail’s Social Sustainability PAF to show a much clearer focus on skills and employment initiatives, and promoting TUCA, the Jobs Brokerage and other Crossrail-sponsored initiatives as potential vehicles for delivering SLNT targets.

The above experience helpfully illustrates the impact that organisational and managerial structures can have in assisting or inhibiting coordination between separate but linked elements of a client organisation’s overall skills and employment strategy. Another possible insight is the inter-disciplinary nature of this work, requiring either close coordination between different specialisms, or alternatively the establishment of a new specialism, combining different elements of knowledge and skill from other areas. To perform the role effectively, future clients should therefore consider assigning, recruiting or developing people who, either individually or in combination, possess the following skill-set:

- Understanding of the construction production process and contractors’ business models, including reliance on subcontract supply chains;

- Understanding of contract management processes – and preferably prior experience of delivering contractor performance through contract management;

- Understanding of skills and employment matters, including the peculiar challenges likely to arise in a construction context;

- Ability to translate strategic objectives into suitable performance management processes;

- Ability to analyse and interpret information with a view to identifying potential risks and opportunities;

- Interpersonal skills, including ability to lead meetings with contractors effectively, with a view to encouraging joint problem solving and dissemination of good practice.

5.3.2 Contractor staffing

As well as changing its own internal organisation, Crossrail’s experience has suggested that clients should also pay closer attention to the staff whom Tier 1 contractors propose to assign to coordinate the delivery of contractual skills and employment targets on their projects.

In Crossrail’s own case, contractual provisions required each Tier 1 contractor:

- To ‘appoint a Responsible Procurement Representative. The Contractor’s Responsible Procurement Representative shall be the primary contact for all Responsible Procurement related matters under the contract’;

- To submit ‘details of the personnel responsible for implementing, managing and reporting SLNT activity within the Contractor’s organisation; the required administration, management and reporting structures’.

Something that Crossrail did not specify, however, was whether the RP Representative should be engaged on these duties full-time or only part-time. The contract also did not say anything about the Representatives’ expected qualifications or experience. Typically, Tier 1 contractors opted at first to appoint someone from one of three different disciplines to fulfil the role, almost always part-time. These disciplines were either HR, Procurement or Community Relations. In a handful of cases, Tier 1 Project Directors even appointed themselves to the role.

Representatives’ willingness and ability to perform the role effectively varied markedly. Partly this reflected differences in the amount of time and enthusiasm that individuals were able and willing to bring to the role: Project Directors, for example, tended not to make successful Representatives. Over time, as the pressure to deliver against SLNT targets increased, most Tier 1 contractors enlarged the time allocated to the role, and on some larger contracts appointed additional staff to support the Representative.

From 2014, when Crossrail started to place more emphasis on Tier 1 contractors’ success in securing SLNT commitments from subcontractors, some RP Representatives from an HR or Community Relations background struggled to make progress. Often, this reflected a lack of experience in managing supply chain relationships and weak links with their own organisations’ procurement, commercial and supply chain teams. By contrast, those from a procurement or supply chain background tended to fare better. Accordingly, whilst it is not impossible for individuals from other disciplines to make a success of the role, Crossrail’s experience suggests that the following supply chain management skills are a particularly important part of the overall skill-set:

- Ability to think and plan strategically;

- Strong relationship management skills; and

- Rigour and persistence in obtaining internal and supply chain skills and employment commitments at the outset, and then following up to ensure these are delivered.

Recommendation 3:

Future clients should pay close attention to the suitability of their own and contractor personnel charged with direct responsibility for delivering contractual skills and employment targets (and any related RP/ social sustainability objectives). In particular:

- There should be close collaboration between the various disciplines and individuals employed within the client’s own organisation to deal with employment and skills matters, possibly as part of a single team or department;

- A client should ensure that, either individually or collectively, its employment and skills team possesses the full range of knowledge and skills required to drive contractors to deliver on their targets;

- Each individual nominated to act as a Tier 1 contractor’s lead for delivering on targets should be scrutinised to ensure that they have sufficient time, supporting resources and skills to perform this role effectively, including adequate supply chain management capability.

5.4 Putting appropriate implementation and monitoring resources in place

As explained previously [at 2.3], Crossrail supplemented its substantive skills and employment requirements with a range of implementation and monitoring processes, both contractual (RP Plans, quarterly reports and Jobs Brokerage) and non contractual (PAF). Modifications and additions made during the course of the project offer possibly useful pointers to other clients on how equivalent processes might be best designed in the future.

5.4.1 Ensure contractor delivery plans are robust and kept up to date

Future clients should benefit from at least some contractors now having a better idea of the processes required to deliver contractual skills and employment targets and related objectives, not least because of some of the lessons learned from the Crossrail project. Clients can therefore reasonably expect a higher standard of initial delivery plan than the ‘cut-and-paste’ of contractual provisions which Crossrail often faced in the early days of the project [see 2.3.1]. This is important since many of the Tier 1 contractors who used the opportunity mid-way through the project to upgrade their systems, policies, procedures and resources , subsequently demonstrated improved delivery of output measures of performance, such as their SLNT targets, both in absolute terms and relative to other contracts where these processes remained weak or confused. By the same token, future clients may wish to continue treating contractor delivery plans as living documents, to be updated and amended from time to time so as to reflect further lessons learned and/or changed circumstances.

5.4.2 Maximise the effectiveness of reporting

Whilst Crossrail’s SLNT reporting regime brought some clear benefits (not least a quarterly health-check of Tier 1 contractors’ progress in meeting their obligations), certain difficulties and limitations encountered during the course of the project point to ways in which future clients might improve on this regime. These include:

- Adopting an effective reporting format and technology. The unwieldiness of Crossrail’s original 13-tab reporting template, and ongoing difficulties with Excel in managing the data collected and complex links between data [see 3.2], indicate the importance of thinking through carefully the format which reports should take and the technology through which such reports are submitted. On some projects, clients might be able to supplement contractor reports, or even replace them altogether, with information collected from employers and individuals as part of the site induction and/or access control process – although the reliability of this information would still need to be subject to some form of independent verification.

- Differentiating between skills and employment and other reporting requirements. Preferably skills and employment reports should cover skills and employment priorities only, and be kept separate from reports relating to other considerations (for example, on Crossrail, the broader reporting requirements around numbers of local people employed).

- Avoiding criteria on which reliable reporting data may be difficult or impossible to obtain. Where – as with questions about duration of a previous period of unemployment, or whether a new job starter or apprentice remains in employment several months or even years later on – reliable reporting data may prove difficult or impossible to obtain, clients might want to consider alternatives. These could include replacing such criteria with targets centred around a Tier 1 contractor’s and its supply chain’s engagement with a specific employability programme with which the client or contractor has a direct relationship and therefore a greater likelihood of being able to verify information of this sort. Another option could be to place less emphasis on trying to track long-term outcomes, and more on steering contractors towards adopting ‘input’ measures proven, in general, to lead to better long-term outcomes: for example, by encouraging or requiring take-up of apprenticeships at NVQ level 3 and above, rather than at level 2.

- Supplementing written reports with face-to-face contact. Crossrail’s own experience confirmed the various benefits of talking through Tier 1 contractors’ reports with them at least once every quarter. These included not only checking the accuracy and validity of the report contents, but also incentivising contractors to complete the reports in the first place and exploring ways in which both the reports and the delivery plans and processes underlying them might be improved in future.

5.4.3 Manage contractor performance

Systematic performance management through the PAF system assisted Crossrail in steering contractors in its preferred direction, first in relation to delivery of the SLNT targets themselves [see 2.4], then in encouraging wider diffusion of supportive management processes, procedures and resourcing arrangements [see 3.8]. Future clients may therefore want to give serious consideration to instituting similar performance management systems of their own. A separate learning legacy report provides fuller details about the design, evolution and benefits of Crossrail’s Social Sustainability PAF. For present purposes, the main benefits can be summarised as follows:

- Providing an alternative incentive for contractor performance, to make up for the fact that Crossrail, as a one-project organisation, had no power to incentivise through promises of repeat work. The main elements of this alternative incentive included the visibility generated by regular assessments, peer pressure (considerably enhanced by the use of charts portraying contracts’ relative position) and the sharing and celebration of good practice.

- Encouraging contractors to innovate above and beyond contractual requirements, and thereby partially overcoming constraints imposed by public procurement rules on what contractual clauses can and cannot require.

- Enabling Crossrail to make adjustments in particular areas over time. The development of a second version of the PAF in 2013-14, for example, allowed Crossrail to incorporate lessons learned from implementation of the original PAF and to modify its own priorities to reflect the changing nature of the project ( placing more emphasis on supply chain management to reflect the greater reliance on subcontractors during the stations and system-wide fit-out phase).

5.4.4 Provide supportive programmes and partnerships

Future clients should give thought to what additional programmes or resources to make available to contractors in order to support delivery of SLNT targets and other social sustainability objectives. These may be provided by the client itself in house, or through partnerships with third party organisations possessing established systems or expertise for Tier 1 contractors to draw upon.

In the case of Crossrail itself, the number and range of programmes and partnerships grew steadily over the lifetime of the project, reflecting gaps in provision which Crossrail in consultation with its contractors decided should and could be filled. As contractors’ own understanding and experience grows, future clients may be able to take less of a lead in this area, relying instead on industry or contractor-led programmes and institutions [see further 5.7e)]. In the interim, however, the following list of initiatives undertaken on Crossrail should provide a guide on what might need to be covered:

- Establishment of a Jobs Brokerage in partnership with Job Centre Plus, together with links with local authority jobs brokerages, to help gain access to unemployed job seekers;

- Establishment of a project training facility (TUCA) and partnerships with existing colleges/ training organisations to help deliver relevant and high-quality apprenticeships, up-skilling in priority areas, and effective pre-employment training;

- Partnerships with specialist and community-based organisations to target those with particular backgrounds or disadvantages in the labour market, with a view to boosting, for example, participation in job starts, apprenticeships, work placements and graduate schemes;

- Links with local schools and colleges, to facilitate the transition from education to work, in particular for those at a disadvantage in the labour market – for example, through improved access to work experience, work placements and apprenticeships;

- Encouragement and support for emerging industry-led programmes to improve employment opportunities, skill levels and/or inclusion in the construction and engineering sectors.

Recommendation 4:

On top of the targets themselves and questions of staffing, clients should also pay attention at an early stage to the monitoring and implementation resources they will have in place to assure and support optimum delivery of their strategic skills and employment objectives. This is liable to involve considering how to:

- Ensure contractor delivery plans are robust and kept up to date;

- Maximise the effectiveness of reporting;

- Manage contractor performance;

- Provide supportive programmes and partnerships.

5.5 Securing wider organisational support

Targets, specialist staff and monitoring and implementation processes all necessarily operate within a wider organisational context. This context must also be taken fully into account when designing a skills and employment strategy and, above all, during the implementation phase of that strategy. In practice, winning ‘hearts and minds’ is, if anything, even more important than the design of the targets themselves or the competence of the technical specialists charged with delivering them. This principle applies equally to both client and contractor organisations.

5.5.1 Client organisation

Within Crossrail, senior leadership support was fortunately never in doubt, particularly when it came to apprenticeships and the work of the Jobs Brokerage. A strong governance regime ensured that Crossrail’s Chairman and Executive received regular updates on Tier 1 contractors’ performance with regard to SLNT and related areas, and were well placed to escalate any persistent concerns to their peers on the contractors’ side. Elements of this governance regime are outlined in more detail in separate learning legacy reports on the Crossrail Skills and Employment Strategy and ‘Delivering Crossrail, UK: A Holistic Approach to Sustainability’.

By contrast, middle-ranking colleagues at site level, such as Project Managers, Project Business Managers and Contract Administrators were less able to focus on providing support. This proved a significant obstacle to progress in some cases, since any show of relative indifference from the local Crossrail team inevitably reinforced any similar sentiments held by the Tier 1 contractor organisation. By the same token, on those contracts where the local Crossrail team offered explicit and sustained support, this tended to galvanise otherwise unenthusiastic Tier 1 contractors into action, and drove ambitious Tier 1 teams to aim still higher.

Various factors probably contributed to this rather mixed picture. Inevitably, many Crossrail site teams’ principal focus was on working with their Tier 1 contractor to achieve direct construction and commercial outcomes, with limited time to consider wider matters beyond the conventional areas of safety, quality and environmental performance. This lack of a sense of ownership was probably further compounded in the early days of the project as specialist skills and employment staff, based in Crossrail’s head office, sometimes escalated concerns too rapidly to members of the Executive, rather than seeking to work through the contractual mechanisms operated and controlled by site-based teams. In these circumstances, in retrospect more should probably have been done to win the hearts and minds of site teams earlier on. From 2013 onwards, more attention was paid to building stronger internal relationships, and communicating in a more easily understandable and sympathetic way Crossrail’s skills and employment expectations, and the assistance required from site teams if Tier 1 contractors were falling short of expectations.

The suggestions made previously in Recommendation 2 about ensuring skills and employment targets are simple and meaningful should also help make it easier to ‘sell’ such targets, and the strategic objectives underlying them, to a busy and potentially sceptical internal audience. Similarly, a better understanding of contract management processes and protocols, as canvassed in Recommendation 3 above, should also help specialist staff build stronger and more productive relationships with site-based teams. In future, client organisations might also consider incorporating skills and employment priorities into Project Manager’s and other relevant staff’s annual performance objectives, and using techniques such as 360 degrees appraisal to ensure that internal specialists can contribute to rating of site teams’ performance (and potentially vice versa).

5.5.2 Contractor organisation

In the early days of the project, organisational support among Tier 1 contractors varied considerably, with genuinely effective support more the exception than the rule. Other than in one or two cases, RP Representatives struggled to secure consistent cooperation from relevant colleagues in procurement, supply chain and commercial functions. In some instances, these problems related to weaknesses in the RP Representative’s own disciplinary background (viz. earlier comments about HR and Community Relations at 5.3.2, above). Another important factor, however, was the often sketchy or inaccurate allocation of roles and responsibilities set out in Tier 1 contractors’ original RP Plans, leading to confusion, inadequate coordination and a lack of accountability.

Crossrail’s response to these issues by 2014 was to insist on amendments to all contractor RP Plans, including much clearer definitions of roles and responsibilities for delivery of SLNT and other social sustainability obligations on each contract. These helped to reinforce the ultimate accountability of the RP Representative, whilst at the same time spelling out how others within the Tier 1 organisation, up to and including the Tier 1 Project Director, should support the Representative in discharging this obligation. Changes to the Social Sustainability PAF reinforced this requirement (rendering several RP Plans “non-compliant” in the first instance), motivating most, if not all, Tier 1 contractors to strengthen the role of the RP Representative and increase wider organisational support.