Managing Construction Noise and Vibration in an Urban Environment

Document

type: Case Study

Author:

Colin Cobbing BSc(Hons), CEnvH, MCIEH, MIOA, Andrew Bird BSc (Hons) MIOA, Cathy Myatt MA MSc, Rhian Locke BSc MSc CEnv AIEMA, Lorna Mellings BSc MSc CEnv MIEMA, Melissa Wellings, Ashley Webb

Publication

Date: 14/03/2017

-

Abstract

Noise was one of the main impacts and challenges during the construction of the Crossrail project. It was recognised that for Crossrail’s Tier 1 contractors to achieve the necessary levels of performance in noise management, focus could not solely be on controlling or minimising noise levels. Factors such as community engagement, effective planning, management processes, leadership and culture were identified as being critical to successful noise management on sites.

This case study describes the detailed suite of performance criteria that were developed for construction noise and vibration management with the aim of driving improved performance. It sets out how the process evolved throughout the Crossrail construction works and the further guidance that was developed to encourage contractors to reach the top levels of performance. Examples from the contractors who have achieved the top level of performance are provided to demonstrate how the performance measures were used in practice.

The criteria defined in this case study have been demonstrated through the process to be effective performance indicators of construction noise management, and have lead contractors to the focus on and prioritise these areas of management. As such, this document may be of use to Clients considering developing a means of measuring the construction noise management performance of their principal contractor(s) on a construction project in an urban environment, and for Principal Contractors in turn to manage and measure the construction noise performance of their supply chain.

-

Read the full document

Introduction

The Crossrail construction works have taken place over a 9 year period (from the start of enabling works to the operation of the railway) and required major civil engineering works such as construction of the tunnels and underground stations at locations in close proximity to residential as well as commercial properties, often with essential works taking place during the evening, night and weekend for necessary engineering and safety reasons.

The control of noise, and to a lesser extent vibration, during construction has been one of the key challenges faced while delivering the programme. Crossrail’s parliamentary assurances required the project to obtain and work within the CoPA Section 61 consents. Crossrail cascaded this requirement to all principal contractors and worked with the Local Authorities to develop a process for contractors to seek, obtain and work within Section 61 consents. Crossrail provided a guidance note detailing the Section 61 requirements.

Due to the nature of the works, Crossrail’s assurances also required noise insulation and temporary re-housing to be offered to the occupiers of dwellings where the noise was likely to cause acute disturbance for substantial periods of time. These environmental requirements are similar to those adopted by other major infrastructure projects such as HS1, the Thameslink Programme and now HS2.

The main legal provisions controlling noise from worksites are contained in the Control of Pollution Act 1974 (CoPA)[1] and require contractors to use Best Practicable Means (BPM) to minimise noise and vibration. BPM is the fundamental requirement for controlling construction noise and vibration from worksites. However it is important to recognise that BPM does not set fixed standards and will change over time or depending on site specific context. What was considered to be reasonable 20 years ago may not be considered to be so nowadays. Construction practice is continually evolving in the light of new technology and best practice set by the construction sector and major infrastructure projects have the potential to play a significant role in driving forward the standards that are used to manage construction noise and vibration.

As a result of the scale and duration of the potential impacts of construction noise on local communities, Crossrail aimed to do more than just meet the minimum standards. The construction works were undertaken by Tier 1 construction contractors (further referred to as contractors). Crossrail’s performance in construction noise management therefore relied upon the combined performance of all of the contractors. Once the construction works were underway, it became clear that the focus could not solely be on contractors controlling or minimising noise levels. Factors such as community engagement, effective planning, management processes, leadership and culture were identified as being critical to successful noise management on sites. In order to provide guidance to contractors on improving performance across this wider definition of construction noise management, Crossrail developed a set of performance criteria. These criteria were incorporated into Crossrail Performance Assurance Framework which provided a mechanism for scoring and reporting on contractors’ performance, which is detailed in the Environmental Supplier Performance paper. As part of this process, the performance of contractors was assessed approximately every six months, over a three year period, and contractors had to prepare an improvement action plan with the aim of improving their performance.

This paper describes the performance criteria that were developed for construction noise and vibration management. It sets out how the process evolved throughout the Crossrail construction works and the further guidance that was developed to encourage contractors to reach world class performance, with examples on how contractors have implemented them. Results of the performance assurance are provided to show how performance of contractors improved. Examples from the contractors who have achieved the top level of performance (known as ‘world class performance’) are provided to demonstrate how the performance measures were used in practice.

The Construction Noise and Vibration Performance Criteria

The criteria used to assess construction noise and vibration performance evolved as the process was implemented. Initially a performance matrix was developed that set out guidance around the following categories:

- Leadership, staffing, interfaces and culture

- Engagement with community relations and stakeholders

- Section 61 Consent Application Compliance, BPM and monitoring techniques

There were four levels of performance identified for each category as follows:

0 = Non Compliant performance (i.e. not meeting the obligations under the contract)

1 = Compliant performance (i.e. meeting the obligations under the contract)

2 = Performance beyond the obligation of the contract and is termed “Value Added”, good industry practice

3=Performance significantly beyond the obligation of the contract, recognised as “World-Class”

The matrix was written in a way that recognised that the steps taken should be proportionate to the scale of the impacts and be case specific. It was considered necessary therefore to build a degree of flexibility into the assessment matrix. Not all the elements were equally weighted and more emphasis was given to particular aspects in order to reflect the circumstances associated with different sites. Neither was it considered necessary to meet all the criteria in order to achieve an overall performance rating or score. For example, the matrix allowed for relatively weak performance on one aspect of management if it was outweighed by excellent performance on other aspects of noise and vibration management, especially where it was considered that the emphasis given those aspects where excellent performance was achieved reflected the circumstances and challenges associated with a particular site or contract package.

The contractor was assessed on their performance against the various categories set out in this matrix and given an opportunity to provide supporting evidence. This evidence was then reviewed by the Crossrail assessors to arrive at a score. A one size fits all approach was not considered to be appropriate and the assessors used professional judgement in determining the final score. The potential for introducing individual bias was overcome through moderation of the results to ensure a level playing field as far as possible. The outcome was then fed back to the contractor, along with performance actions required to improve the scores on the next iteration.

Guidance on Developing a Noise and Vibration Action Plan

The process of supplier performance assurance, using the construction noise and vibration performance criteria, worked well, with contractors moving from non-compliant to compliant performance and value added performance. Contractors were then challenged to improve their performance towards “world class” performance and empowered to take ownership of their performance, by encouraging them to develop noise action plans that set out current performance across the different criteria and then specific milestones being targeted to achieve higher scores, with accompanying dates and deadlines.

It was recognised that the criteria set out in the matrix to define world class performance, were general in nature and that this level of performance relied more heavily on professional judgement than other levels of performance. It was very dependent upon the circumstances at each site, the activities being undertaken and the inherent risks and opportunities for improvement.

Feedback received from contractors as part of the supplier performance process indicated that further guidance on how to reach world class performance would be useful. Consequently, a guidance framework was developed for contractors to develop actions towards performance improvement. As contractors started to achieve the top levels of performance, a number of examples were developed and these were shared to encourage others to improve performance.

The guidance set out six action areas as follows:

- Strong culture of effective management

- Community engagement

- Innovation

- Effective planning

- Collaboration

- Compliance with regulatory requirements

Some of the aspects are particular to, or more relevant to, major construction projects. However, most of the aspects have wider applicability to all construction activities. Some of these action areas directly linked to the supplier performance scoring matrix. For example actions around developing a strong culture of effective management linked directly to the criterion on leadership, staffing, interfaces and culture. Other action areas such as innovation and collaboration were cross-cutting and could be scored under any of the criteria (as appropriate).

A summary of each of the action areas is presented below as well as some examples of the actions that were taken. Two case studies are described at the end of the document on two sites which achieved a world class performance. They detail the actions taken in each of the six action areas.

Strong culture of effective management

The Crossrail worksites were large and typically comprised numerous people involved in different aspects of the works e.g. procurement, design, execution and supervision of the works. It was identified that wrong or inappropriate behaviours adopted by people working both off and on the site could lead to excessive and unreasonable noise and/or vibration. Conversely, it was considered that the best performance would typically be achieved on sites where all members of the team were focused on minimising this disturbance. The key elements were identified as:

- good leadership;

- clear definition of roles, responsibilities and accountabilities;

- effective supervision;

- training and information on any noise or vibration control restrictions or requirements; and

- good communication to instil the right behaviours throughout the organisation.

Several contractors appointed ‘noise champions’, key personnel to take on responsibility for good noise management and influence decisions on applying best practicable means (BPM). This proved to be an effective means of instilling a culture of effective management. The job of the Noise champion is described in the role description for reference.

One contractor used posters to display information on people with specific roles and responsibilities for construction nose management. The posters were displayed around the worksites and offices. This meant that everybody involved in the works were provided with clear and accessible information about members of staff with particular roles and responsibilities and who they should contact if anybody on site wanted to share observations or make suggestions about ways to improve.

Community engagement

Many of Crossrail’s construction sites were located in close proximity to local communities, with people living, working and undertaking other activities in the vicinity of the works. Minimising impacts on people is quite different from controlling or minimising noise levels. Community response to noise is strongly influenced by people’s attitudes towards the noise creator. In this context, the approved Code of Practice for construction noise acknowledges that “…people are more likely to tolerate the noise if they consider that the noise is necessary and that all reasonable steps are being taken to control and minimise noise impacts” [2]. It is for this reason that Crossrail required a number of community engagement and communication deliverables from it’s contractors via the contract, which translated as requirements for ‘compliant’ or a score of 1, in the noise framework.

For example, Crossrail and its contractors had Community Relations staff to respond to complainants and deal with the specifics of their issue. Noise complaints triggered an investigation into on-site activity to review BPM and implement corrective action where practicable. These outcomes were then reported back to the complainants where possible. More complex investigations occasionally required monitoring to be carried out at the complainants property to ascertain the source of the disturbance, and to check whether Crossrail’s noise and vibration mitigation policy had been administered correctly.

Community Liaison Panels were also held regularly, chaired by the Local Authority, so that Crossrail and its contractors could present updates to the local community and facilitate a two way dialogue. Residents’ feedback was often translated into actions with progress tracked at subsequent meetings. Often the requests were for more specific information (e.g. about the works and why they were required), so Crossrail could present information about these specifics with the right people in attendance at a following meeting.

In order to reach levels of world class performance, contractors were challenged to go beyond these requirements and to build trust and confidence with communities that would positively influence people’s attitudes towards the works and any disturbance from noise. For example, several contractors arranged open days so that residents could visit worksites and observe how the works were being organised and undertaken. This proved to be an effective means of breaking down any negative perceptions that some residents had about the way in which some of the worksites were being managed. This was especially true for a number of sites where it was not possible to see the works from vantage points outside the worksites.

Providing regular updates as to when and where noisy works would be taking place was also recognised as an effective way of engaging the local communities. One contractor produced a weekly notification sheet which was hand delivered to the surrounding residents so that they were kept abreast of when the works would be near them and over what working hours.

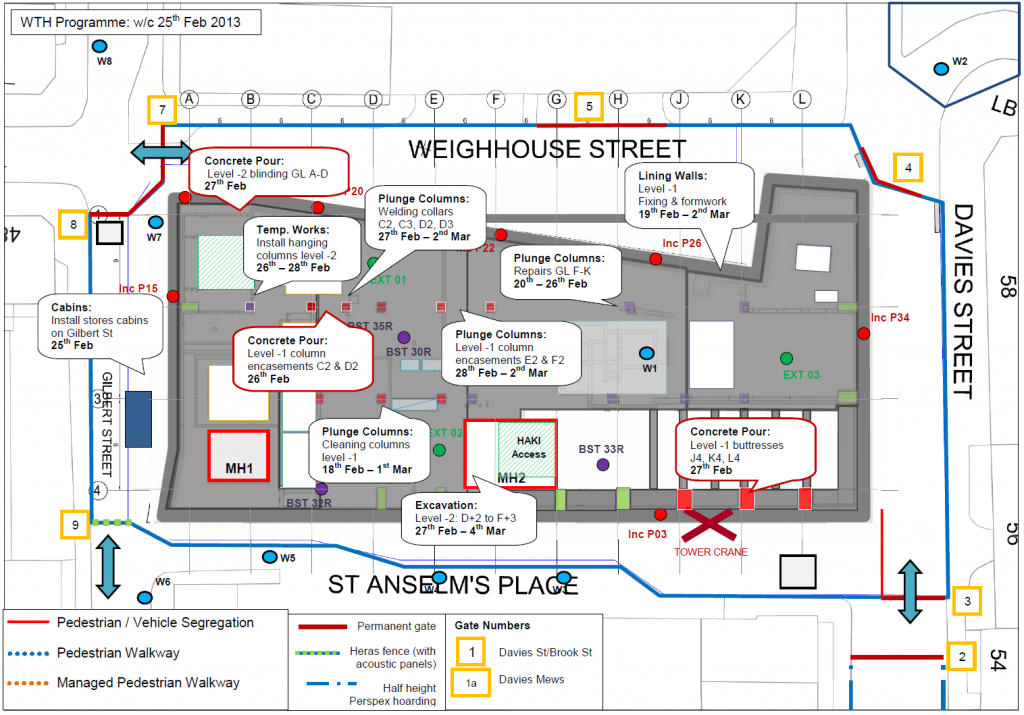

Figure 1 – Engaging the Community and updating on Progress

Innovation

It was found that reaching the top levels of performance involved more than following established best practice. Innovation was therefore identified as an important differentiator between compliance and World Class performance.

There were numerous examples of physical noise reduction measures such as acoustic sheds and innovative pile extraction and there was a particular focus on using quieter demolition techniques such as pulverising, hydraulic concrete bursting, Nonex (non-explosive expanding charge material), and saw cutting. The final amount of material that was demolished or reduced using such methods was relatively extensive.

However some of the other innovations proved to be equally effective as the physical innovative methods. These included the use of different communication tools to rapidly communicate with residents and stakeholders, zoning the site working hours based on neighbouring sensitivities (e.g. working in residential areas during the day and commercial during the night), use of plastic bins for metal rather than clanging it into skips at night, putting up signs in a variety of languages to remind workers to minimise noise and distilling the sometimes complex Section 61 consent information into a bullet point summary of what working hours are allowed for different activities. Visual noise alerts (a traffic light system) were also used innovatively to improve plant operator awareness of their noise emissions.

Noise monitoring technology also advanced during the Crossrail project, with real-time monitoring systems becoming more widely available. These were used on numerous sites and proved to be very useful for a number of reasons. It allowed the triggers and alerts to be reprogrammed remotely as often as required, e.g. if a dispensation increased the predicted level. This was particularly useful when there were multiple contractors working on one site, as the cumulative level could regularly change, and the personnel that need to be on the alerts could often change. It also allowed the results to be accessed remotely and reports to be run off automatically. This allowed Crossrail to share the data with Local Authorities faster and more transparently.

Figure 2 – Noise Technology to Assist Mitigation

Effective planning

It was considered that the best outcomes would be achieved if noise management was considered as an integral part of the overall management of the works and was considered well in advance of the start of the works. For example, at Westbourne Park, it was possible to incorporate asset protection measures as part of site set up adjacent to the operational railway, thereby protecting the workforce and also avoiding or minimising the amount of possession working or working during engineering hours. At Paddington Station, there was a concern that breaking into the diaphragm walls would generate significant levels of vibration at the nearby Grade 1 listed building. As part of the temporary works design the rebar was de-bonded to allow drill and burst methods to be used to reduce diaphragm walls instead of having to use mechanical breaking which significantly reduced the levels of vibration. A case study on Noise and Vibration details this example.

Figure 3 – Methods to mitigate noise and Vibration

Effective planning was considered necessary to produce good management plans and consent applications, to engage effectively with external stakeholders and to identify cost effective solutions. Good planning in the Section 61 processes was necessary for the production of good quality applications and early engagement in the consenting process. To achieve this, some contractors integrated their noise and vibration specialists into the construction team, for example by attending the construction planning meetings.

The early provision of noise and vibration risk assessments was also identified as important because they could inform the planning process if used early enough. In particular, the results of noise calculations were used to inform decision making about the selection of plant and working methods to minimise noise impacts where they would be most felt.

Figure 4 – Detailed pre-planning

Crossrail was committed to providing noise insulation packages and temporary rehousing where, despite taking all reasonable steps to minimise noise from the site, the residual noise levels were likely to cause acute disturbance for prolonged periods of time. However, such measures can take a long time to implement, especially if listed buildings are involved. Where such measures applied, effective planning was necessary to identify qualifying dwellings.

Collaboration

Crossrail construction works involved numerous parties and interfaces, who often had competing objectives or constraints. Effective noise management required compromise to be reached and common objectives to be agreed, so that the right mitigation could be incorporated. Effective collaboration, underpinned by good communication, was therefore identified as being vital to ensuring that everybody involved was engaged and working together towards achieving these common objectives. This spanned client and contractor side e.g. project managers/directors, civil engineers, site supervisors, community relation representatives, environment managers, noise specialists, procurement managers and site operatives.

Local authorities have the powers to restrict hours of working or specified plant and machinery if such restrictions are reasonable and necessary to protect local residents. However, such restriction can significantly affect the cost of the works and the programme. Those responsible for works will typically prefer the local authority to consider alternative steps to minimise noise without imposing such restrictions, especially if those steps can achieve similar if not better levels of protection. Open, transparent and collaborative working with the relevant local authority was identified as important in terms of effectively communicating with the people involved in managing the works and the processes to be used to minimise construction noise and vibration. The best results were achieved when those responsible for the works had built a high level of trust with the local authority so that they could be confident that the works may be allowed to proceed in the most cost effective and expeditious manner without compromising on the level of protection to be afforded to local residents.

Compliance Controls

The final criterion that was identified was demonstrating compliance and control mechanisms were in place to ensure that legal duties and consent requirements were always met. This was considered to be critical to building confidence with the local authority and local communities.

For example, contractors carried out regular inspections to ensure that best practicable means to control noise were being implemented on the site (BPM inspections) and extensive noise and vibration monitoring was also undertaken, including semi-permanent real-time monitors at key receptor locations and weekly attended monitoring. The weekly attended monitoring visits (undertaken by noise and vibration specialists) were also an opportunity to assess that BPM was in place on site and validate the Section 61 predictions.

A summary of the BPM inspections and the monitoring results were presented to the Local Authority at monthly meetings to ensure transparency, discuss any noise exceedences or complaints and track ongoing actions. Joint site inspections involving the Contractor, Client and Local Authority were regularly undertaken to ensure that BPM was maintained and new opportunities for improvement were identified and progressed. Some contractors produced quick guides which distilled key Section 61 consent information and requirements into an easy to read format and which were displayed on site and also communicated electronically. Regular engagement with the workforce through site briefings, training and awareness sessions was also undertaken.

Results

Performance was scored in accordance with Crossrail’s supplier performance process, with each contractor being assigned to one of four categories. These were non-Compliant performance (i.e. not meeting the obligations under the contract, also known as the Works Information (WI)), Compliant performance (i.e. meeting the obligations of the WI), Value Added performance (i.e. working beyond the obligations of the WI) or World-Class performance (i.e. working significantly beyond the obligations of the WI). As demonstrated in Figure 5 below, there was a steady improvement in the rating of performance over the duration of the assessments from round 1 (in 2012) to round 6 (in 2016).

Figure 5 – Average noise score per round

The average shows the overall average score of all contractors per assessment round. This shows that by round 6, the average score was above 2 – Value Added performance.

The final round also shows that six contractors out of the twelve assessed, achieved world class performance, listed as follows:

- C405 Costain Skanska Joint Venture – Paddington Station.

- C412 Costain Skanska Joint Venture – Bond Street Station.

- C422 Laing O’Rourke Infrastructure – Tottenham Court Road Station.

- C502 Laing O’Rourke Infrastructure – Liverpool Street Station.

- C510 Balfour Beatty, BeMo Tunnelling, Morgan Sindall and VINCI Construction Joint Venture – Whitechapel and Liverpool Street Station Tunnels.

- C610 Alstom Transport, TSO and Costain Joint Venture – Tunnel fit out.

Conclusion

This case study has shown how Crossrail developed a noise performance framework and scoring matrix that incorporated wider factors relating to noise and vibration management including community engagement, effective planning, management processes, leadership and culture. It also sets out the further guidance that was provided to contractors on developing action plans to reach the top levels of performance.

The performance framework, and subsequent noise and vibration action plans provided a tool that contractors could use to set goals for improvement but allowed flexibility for contractors to identify and agree priorities to reflect the particular circumstances and challenges that existed at individual sites. Scoring then provided a mechanism to motivate and reward good performance. The criteria and guidance defined in this case study have been demonstrated through the process to be effective performance indicators of construction noise management, and have lead contractors to the focus on and prioritise these areas of management. Using these tools, Crossrail’s contractors were able to demonstrate an improvement in performance over the construction period, including six contracts reaching the top levels of performance.

References

[1] Control of Pollution Act 1974 (CoPA) [online], available at:

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/40/part/III/crossheading/construction-sites

[2] Code of Practice for construction noise

BS5228-1(2009 + A1:2014). Code of Practice for Noise and Vibration Control on Construction and open Sites

Examples of world class performance

The following 2 examples are provided by two of Crossrail’s contractors that have achieved ‘world class’ status and gives a concise summary of how this was achieved.

Example 1

C412 Costain Skanska Joint Venture – Bond Street Station

The Bond St. Station project consisted of the construction two ticket halls and tunnel connections in the heart of Mayfair. The Western ticket hall was surrounded by residents and an antique emporium housing valuable objects that were susceptible to vibration. This was in contrast to the Eastern ticket hall site which was based in a commercially dominated area. It was therefore paramount to effectively tailor the noise and vibration control and mitigation measures to minimise disruption to the local stakeholders. To successfully achieve this, a number of areas were key to delivering effective noise and vibration mitigation across the project:

• Strong culture of effective management– There was a clear focus throughout to engender the right behaviours amongst everybody involved. For example, pledges were made by the leadership teams to aspire to world class performance, and structures and systems were put in place to drive the performance. Everybody was encouraged to play their part. Engineers and supervisors were encouraged to proactively report noise related issues and provide feedback on the steps that were working well, as well as those that did not work well. There were active noise champions on site who played a key role in ensuring that best practice was used and, specifically, Section 61 consent conditions were adhered to. Regular team briefings and toolbox talks were delivered by the Noise and Vibration specialists and project environment team. Awareness was raised throughout the whole workforce by holding regular toolbox talks on noise control measures and specific months were designated to noise and vibration awareness to coincide with programmed noisy activities.

• Community Engagement – Community relations was considered to be an integral component of the overall programme to reduce impacts. Feedback channels were built up through regular meetings with local residents, where they were consulted on the steps to be taken to minimise disturbance from noise. This included consultation on working hours especially when options for different working patterns were available. Stakeholders were invited on monthly trips to key attractions in London in order to provide some respite and to connect the community. The aim was that the support networks that were built would endure after the works have been completed. A questionnaire was trialled to gauge stakeholder satisfaction with noise and vibration management. This was administered to a number of community representatives with the aim of identifying any areas of concern.

• Collaboration – There was a focus on collaboration and team engagement to bring all parties together to deliver high levels of performance. For example, the noise and vibration specialists, client, project environment team and engineers regularly attended noise management workshops to identify issues and to agree best practice noise control and management methods in advance of the works. Monthly meetings were also held with Local Authority officers to agree the steps to be taken to minimise noise impacts.

• Effective planning – This was used to build in noise reduction measures as early as possible. For example, there was early engagement with the previous contractors to ensure that lessons learned from the earlier works were built upon. Manufacturers of equipment and the supply chain were engaged to ascertain whether further noise attenuation could be engineered or alternative quieter equipment / working methods could be utilised in advance of the works. For example, a large ventilation fan was designed with a bespoke acoustic enclosure to avoid problems that had previously occurred with ventilation equipment that had been used by a previous contractor.

• Innovation – Physical control measures were implemented to mitigate noise. These included bespoke acoustic enclosures for static plant such as concrete pumps and the ventilation fans, along with acoustic blankets around all noisy works and gates. Quieter versions of equipment were procured where feasible, such as the 100 tonne crane and concrete pumps.

• Compliance – The site achieved a 100% record of seeking and obtaining Section 61 consents well before the start of works. This was due in part to the proactive workshops that were held several weeks if not months in advance of those activities requiring consent. A Section 61 process flowchart was also compiled by the noise and vibration champion to assist the engineers when planning for works. A summary of consented works was sent out to the engineers and site supervisors as a means of checking and challenging whether all of the upcoming construction activities were fully consented. This additional process was introduced to ensure that all works arising from changes to the programme of other unforeseen changes were fully captured.

• The site also had a 100% record of compliance with the Section 61 consent. This was in part due to the checks and processes in place (detailed above) and the effective feedback loop between the engineers and the environment team to ensure that no unconsented works took place. Regular BPM inspections were carried out by the environment team. Extensive noise and vibration monitoring was also undertaken, including semi-permanent real-time monitors at key receptor locations and weekly attended monitoring. A summary of the BPM inspections and the monitoring results were presented to the local authority at monthly meetings to ensure transparency, discuss any noise exceedences or complaints and track ongoing actions. Quick guides were produced which distil key Section 61 consent information and requirements, which were then displayed on site and also communicated electronically.

Example 2

C422 Laing O’Rourke – Tottenham Court Road Station

The Tottenham Court Road (TCR) Station project consisted of the construction of two ticket halls and tunnel connections in the heart of Soho. The Western ticket hall was surrounded by a diverse variety of sensitive receptors, including residential, offices, schools, a music recording studio, restaurants, hotels and hostels, a medical centre and the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC). The Eastern ticket hall was also surrounded by a wide range of sensitive receptors, including residential properties, a church, a pub, a nightclub, shops and offices.

This presented particular challenges with regard to working hours, due to the conflicting sensitive hours of the receptors, making daytime, evenings and night-times all sensitive periods. Due to these constraints, world class noise management was recognised as being essential for success at this site and there was real momentum and drive to achieve this from day one on site. This started with engaging the project leadership and getting a written commitment of their support to achieve world class noise management. An action plan was then developed collaboratively with contractor, client and noise and vibration specialist, which set out the key milestones against target dates. These milestones and achievements are set out below.

Strong Culture of Effective Management – A culture of noise awareness and collaboration around noise issues was achieved on this contract. Noise awareness campaigns were continuously rolled out to ensure new staff were aware of the sensitivities of the site and also to encourage 360 dialogue on improvements or innovations to the way noise was managed. This has resulted in positive outcomes, from site operatives identifying noise mitigation solutions out on site, to engineers engaging with the supply chain during procurement to identify means of reducing noise before plant was even brought to site.

The importance of noise management was recognised by senior management and featured on the agenda of the weekly senior management meetings.

Community Engagement –Due to the diverse range of sensitive receptors surrounding the sites, a proactive approach to community engagement was adopted to try and minimise disturbance. For example, ‘quiet times’ were agreed in advance on a weekly basis so that noisy activities were ceased during recording sessions at the music recording studio. Laing O’Rourke allowed the use of their own meeting rooms during a period of noisy work so that a neighbouring commercial property could hold their sensitive meetings.

Information Sheets were issued to the local stakeholders on a regular basis, giving updates on new works and informing residents on any noisy activities that may arise. It was found that by giving detailed honest information about the works, complaints were much reduced.

The Goslett Yard site was adjacent to Saint Patrick’s Church. They had regular services every day and works needed to be planned around those times. This was achieved by clearly displaying the church service times on site notice boards, providing written quiet times in method statements and communicating this information at the site induction.

Innovation – A number of new initiatives were trialled at TCR. This resulted in the following noise reducing innovations:

• Giken Silent Piling rig was used to install sheet piles during school opening hours without complaint.

• Wire saw was used in place of breakers to break out gantry running beam.

• A Noise Library of source measurements of plant on site was developed to improve accuracy of future noise models.

• Developing the use of social media as a means of reaching out to the community.

• Cloud technology was used to share information such as monitoring data, followed up by training for stakeholders on how to interpret the noise data.

• Results of noise monitoring were used to manage site activity. A live system with early warning (amber) levels and noise alerts were sent to construction managers.

• Knowledge was shared with other contractors.Effective Planning – Early planning of works was used to enable efficiencies and noise control to be integrated into the works. For example:

• Through the use of digital engineering 95% of the rebar was pre cut off site, thus reducing noise disturbance and expediting the programme.

• By using an in house developed logistics tool, lorry movements were planned in such a way to reduce noise and congestion around the site.

• The environment manager worked closely with the procurement manager to enable tonal alarms to be eradicated prior to subcontractors starting on-site.

• The S61 consent application process was used to ensure noise was on the agenda when planning works. This was achieved through cycles of applications for 6 months of works, planned 3 months in advance and approached in a collaborative manner to join together noise specialists, engineers and environmental managers on both client and contractor sides.

• A weekly meeting was held with community relations, planning and Crossrail’s construction management team to review a 6 week look ahead programme and identify any areas of works that may be particularly noisy. It was an opportunity to reassess if the BPM was adequate and ensure that residents were notified.Collaboration – There was strong collaboration between contractor and client, integrating various different roles relating to noise management (noise specialist, environment teams, construction teams and community relations teams). For example, workshops were held at an early stage of the S61 application process to ensure that everyone agreed on the content before the noise specialist progressed the application, to avoid rework and expedite any further discussions required around BPM, working methods or hours.

The Environment Manager worked closely with the engineers to identify better ways of reducing noise and to provide a challenge to old ways of thinking i.e. traditional methods such as pneumatic breakers, vibropiling. The Community Liaison Manager worked side by side with the Environment Manager to ensure a joined up approach to investigating and responding to complaints and implementing remedial mitigation measures if required.

Environmental interface meetings were held with other Crossrail contractors in the area to ensure that everyone was aware of each others works and that any cumulative issues could be planned for and managed.

Compliance – Compliance with the Section 61 consent was paramount to a successful project and enhanced the relationship with key stakeholders. Compliance was achieved through regular engagement with the workforce through site briefings, training and awareness sessions.

The project had regular meetings with the Local Authority which nurtured a relationship of mutual trust and transparency. Joint site inspections with Contractor, Client and Local Authority were regularly undertaken to ensure that BPM was maintained and new opportunities for improvement were identified and progressed.

The noise specialist carried out a weekly attended site visit to conduct attended monitoring and assess that BPM was in place on site.

-

Authors

Colin Cobbing BSc(Hons), CEnvH, MCIEH, MIOA - Arup, Crossrail Ltd

Colin has 30 years experience in acoustics. He has spent most of his career working on major infrastructure projects, spanning all different stages of scheme development ranging from: project inception, obtaining major consents, design and specification, procurement, construction, completion and commission testing. The majority of his time has been supporting promoters of schemes and contractors. He has also supported local authorities in the discharge of their planning and environmental health duties.

Colin prides himself on working openly and collaboratively with local authorities, communities and other stakeholders to reduce the scale and extent of noise impacts arising during the construction and operation of major projects.

He joined Crossrail in 2009. Prior to that he was the Noise and Vibration Manager for Network Rail on the Thameslink Programme and for the Hitchin Grade Separation Project. Between 2009 and 2015 he was Crossrail’s Noise and Vibration Manager in the Sustainability and Consents Team. In 2015 he scaled back his involvement to focus on leading the Acoustics Team at Arup. However, he still continues his involvement and is overseeing the completion of the design and installation of the Crossrail track systems in the central section.

Andrew Bird BSc (Hons) MIOA - Crossrail Ltd

Andrew was appointed as the Acoustic Manager at Crossrail in 2015, with responsibility for providing specialist noise and vibration advice to the Crossrail programme, promoting a consistent approach to noise and vibration issues on construction, fixed plant and the operational railway and identifying and disseminating best practice and lessons learned.

Andrew has 10 years experience in acoustic consultancy and has been with Crossrail since 2011. During these 10 years Andrew has had significant involvement in major infrastructure projects, resolving construction noise and vibration issues, producing environmental impact assessments and consent applications. This includes Crossrail, Thameslink, High Speed 2, Thames Tideway, and Defence Training Academy St Athan.

Andrew has also managed the acoustic design of several significant architectural projects, including school, hospital, residential, office, commercial and religious buildings. During this time he has gained experience of advanced noise and vibration modelling, monitoring and data analysis. Andrew is a committee member of the London branch of the Institute of Acoustics and is a Science Technology Engineering & Maths (STEM) ambassador, volunteering in Schools.

Cathy Myatt MA MSc - Crossrail Ltd

Cathy Myatt is the Environment Manager at Crossrail. She leads the environment function, with overall responsibility for assuring compliance with environmental requirements. Her involvement dates from 2003 and includes preparing and submitting the Environmental Statement and negotiation of environmental requirements through the parliamentary Select Committee. She designed and implemented the project’s EMS and was involved with the procurement and assurance of design and construction contracts. She has also driven continual improvement on the project using mechanisms such as best practice fora, the Green Line Recognition Scheme and the supplier performance assurance process. Cathy is also an Associate Lecturer at Birkbeck College, teaching on the MSc in Environment and Sustainability.

Rhian Locke BSc MSc CEnv AIEMA

Rhian was the EMS and Performance Manager for Crossrail from October 2011 to 2016. Rhian was responsible for managing and maintaining the Environmental Management System (EMS) to ensure that it complies with ISO 14001 and relevant legal and other requirements. Her duties included reviewing and providing advice on environment incidents and conducting the management review. Rhian also managed the environment audit function and undertook environmental audits of the Crossrail delivery team, its partners and Tier 1 contractors as a lead auditor. Rhian was responsible for driving environment improvements and lead on the environment input to Crossrail’s supplier performance assurance process where she successfully completed five iterations of verification visits. Rhian also managed the environment training programme and developed and delivered environmental training on areas such as the EMR and incidents across the project. Rhian also took on a direct delivery role within the Liverpool Street station site team. Before Crossrail, Rhian worked for EnterpriseMouchel as a Sustainability Advisor under the Area 3 Highways Agency (HA) managed motorway maintenance contract.

Lorna Mellings BSc MSc CEnv MIEMA - Crossrail Ltd

Lorna is the Environmental Assurance Manager at Crossrail. She is responsible for programme wide environmental best practice through various fora such as the Environmental Managers Forum and she is responsible for the promotion of a positive environmental culture throughout Crossrail, through managing and developing the Green Line environmental engagement award scheme. Lorna also provides technical environmental advice to the business, specifically with regards to excavated material, contaminated land and ecology.

Lorna joined Crossrail in 2008 as a Principal Environmental Planner having previously worked for Carillion on a number of national building projects and the Government’s Aspire Defence Project.

-

Peer Reviewers

Tom Marshall P.Eng. MIOA, Arup

Dani Fiumicelli, Technical Director Noise and Vibration, Temple Group Ltd